- 387 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Global Aging and Challenges to Families

About this book

The recent explosion in population ageing across the globe represents one of the most remarkable demographic changes in human history. Population ageing will profoundly affect families. Who will care for the growing numbers of tomorrows very old members of societies? Will it be state governments? The aged themselves? Their families? The purpose of this book is to examine consequences of global aging for families and intergenerational support, and for nations as they plan for the future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Global Aging and Challenges to Families by Vern Bengtson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gerontology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Global Aging and the Challenge

to Families

Vern L. Bengtson, Ariela Lowenstein, Norella M. Putney and Daphna Gans

The recent explosion in population aging across the globe represents one of the most remarkable demographic changes in human history. Around the world today there is much concern about population aging and its consequences for nations, for governments, and for individuals. It has often been noted that population aging will inevitably affect the economic stability of most countries and the policies of most state governments. What is less obvious, but equally important, is that population aging will profoundly affect families. Who will care for the growing numbers of tomorrow’s very old members of societies? Will it be state governments? The aged themselves? Their families?

Our purpose is to examine consequences of global aging for families and intergenerational support, and for nations as they plan for the future. We will be examining four remarkable social changes during the past fifty years:

- Extension of the life course: Over the past six decades there has been a remarkable increase in life expectancy, and an astonishing change in the normal, expected life course of individuals, especially in industrialized societies. A generation has been added to the average span of life over the past century.

- Changes in the age structures of nations: This increase in longevity has added a generation to the social structure of societies. Most nations today have many more elders, and many fewer children, than fifty years ago.

- Changes in family structures and relationships: Families look different today than they did fifty years ago. We have added a whole generation to the structure of many families. Some of these differences are the consequence of the expanding life course. Others are the result of trends in family structure, notably higher divorce rates and the higher incidence of childbearing to single parents. Still others are outcomes of changes in values and political expectations regarding the role of the state in the lives of individuals and families.

- Changes in governmental responsibilities: For most of the twentieth century, governmental states in the industrialized world increasingly assumed more responsibility for their citizens’ welfare and well-being. In the last decade, however, this trend appears to have slowed or reversed as states reduce welfare expenditures.

How will families respond to twenty-first-century problems associated with population aging? Will families indeed be important in the twenty-first century, or will kinship and the obligations across generations become increasingly irrelevant, replaced by what Phillipson (see Chapter 2) calls “personal communities”?

In this chapter we first review population aging trends projected for the twenty-first century. While European nations have the most aged populations, the pace of aging is accelerating most rapidly in developing nations. In many nations, those aged 80 and over are the fastest growing portion of the total population. Second, we discuss the changes in the age structures of industrialized and developing nations, and the implications for governments and families. Third, we describe how these larger demographic changes are affecting the generational composition of families and the structures of kin availability. Fourth, we discuss the microlevel implications of these trends, as exemplified in family intergenerational relationships and behaviors. We present research addressing such issues as the strength and stability of intergenerational relations, the conflict or ambivalence that can characterize family relationships, and the increasing diversity of family relationships, a consequence of changing family structures. We conclude with some suggestions for future research and policy agendas—to be carried out by the next generation of scholars—concerning families, aging, and social change in the early twenty-first century.

The Realities Of Population Aging

Our global population is aging, and aging at an unprecedented rate. During the twentieth century we became aware of problems associated with the population “explosion” across the globe, and problems of migration from rural to urban areas. But as we begin the twenty-first century, population aging is emerging as a preeminent demographic change. During 2000, the world’s elderly population (aged 65 and over) grew by more than 795,000 people a month. Projections indicate that by 2010 the net gain will be 847,000 older people per month (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000).

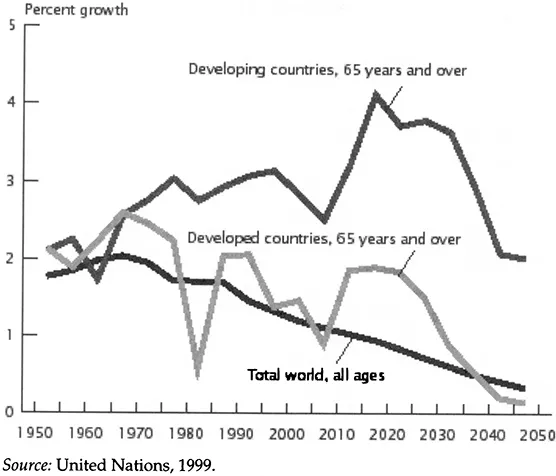

Figure 1.1 Average Annual Percent Growth of Elderly Population in Developed and Developing Countries.

Population Aging: A New Phenomenon

It should be noted that population aging represents a human success story. Societies now have the luxury of aging. But the incremental growth in life expectancy also poses many challenges. The numbers and proportions of elderly, especially the oldest old, will rise rapidly in most developed and many less developed countries over the next decades.

Population aging is occurring in both developed and developing nations. This demographic phenomenon has been discussed most often in terms of its economic consequences for industrialized nation in Europe and Asia. What is less widely noted is that the absolute numbers of elderly in developing nations often are large and everywhere are increasing. In fact, less developed nations as a whole are aging much faster than their more developed counterparts (see Figure 1.1).

Many developing countries are now experiencing a significant downturn in rates of natural population increase (births minus death) similar to what has occurred in most industrialized nations. Well over half of the world’s elderly (people aged 65 and over) now live in developing nations (59 percent, or 249 million people). By 2030, this proportion is projected to increase to 71 percent, or 689 million people (United Nations, 1999; U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000). In Asia and the Latin America/Caribbean area, aggregate proportions of elderly are expected to more than double by 2030.

The current growth rate of the elderly population in the developing countries is expected to rise to above 3.5 percent annually from 2015 through 2030 before declining in subsequent decades (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000). While the aggregate numbers and proportions of elderly in developing nations are increasing faster than in developed nations, it is important to note that the elderly still comprise a significantly lower proportion of the total population in developing nations. As this aging process accelerates, in all nations age structures will change and the elderly will become an even larger proportion of individual nations’ total populations.

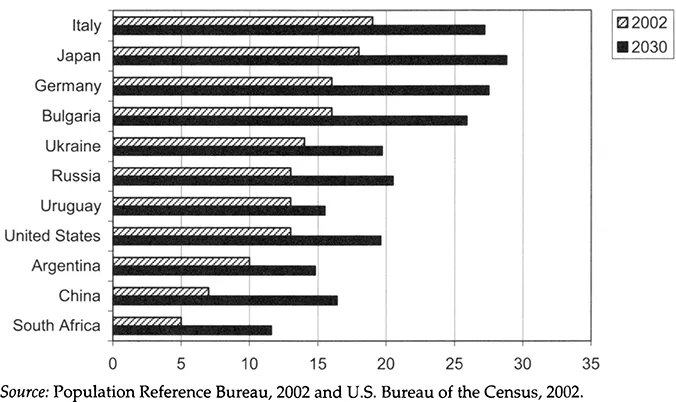

Nations in Western Europe and Japan have the oldest populations in the world. Census projections show that by 2030, most of the Western European nations will have aged (65 and over) populations of 24 to 26 percent (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2002). Japan is perhaps the most rapidly aging society in the modern world. Whereas in 2002 the elderly 65 and older were about 18 percent of the Japanese population, by 2030 this figure will rise to 29 percent (ibid.). By 2050 those aged 65 and over will represent about a third of Japan’s total population (Kojima, 2000). It is not expected that historically low birth rates in Europe and Japan (with total fertility rates around 1.3) will recover in the next several decades, meaning that overall population levels in these nations will continue to decline (Population Reference Bureau, 2002). Currently, Australia, Canada, and the United States have moderately high aggregate percentages of elderly (13 percent), and these rates will increase to between 21 and 23 percent by 2030 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2002). In Israel, an industrialized nation that is relatively young, the 65 and older age group will constitute about 12 percent of the population in 2020 and 15 percent by 2030 (Brodsky, Shnor, and Be’er, 2000; U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2002). Figure 1.2 summarizes the projected changes between 2002 and 2030 in the percentage 65 and older in selected countries.

Figure 1.2 Percent 65 and Older in Selected Countries: 2002 and 2030.

The aging of the aged. We must also consider the secondary aging process, sometimes termed the aging of the aged. Over time, a nation’s elderly population will grow older on average as a larger proportion survives to 80 years and beyond. In many countries, the “oldest old” (people aged 80 and over) are now the fastest growing portion of the total population. In the mid-1990s, the global growth rate of the oldest old was somewhat lower than that of the world’s elderly (65 and over), a result of low fertility that prevailed in many countries around the time of World War I. For example, people who were reaching the age of 80 in 1996 were part of a relatively small birth cohort. Thus the 1996 to 1997 growth rate of the world’s oldest-old population was only 1.3 percent. Just a few years later, however, the fertility effects of World War I had dissipated. From 1999 to 2000, the growth rate of the world’s 80 and over population had jumped to 3.5 percent (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000).

Until recently, Europe has had the highest proportions of population in the most advanced age categories. But in 2000, the North American oldest-old population aged 80 and over equaled that of Europe as a whole, probably as a result of small European birth cohorts around the time of World War I. By 2013, however, these percentages are again expected to be higher in Europe: in 2030, nearly 12 percent of all Europeans are projected to be age 75 and over, and 7 percent are projected to be age 80 and over (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2002). In Japan, those 75 and over will constitute 17 percent of the total population in 2030, and 12 percent are projected to be age 80 and over (ibid.) On the other hand, in Israel, the percentage of the 80 and over population is projected to be 4 percent in 2030 (Brodsky, Shnor, and Be’er, 2000).

We can summarize these population trends as follows.

The world’s total elderly population is increasing at a rapid pace. The combination of improved health and longevity and lowered fertility has generated growing numbers and proportions of older population throughout most of the world. The global population aged 65 and over was estimated to be 435 million people as of 2002, an increase of 15 million since 2000.

The elderly population is growing most rapidly in developing countries. Population aging has become a well-publicized phenomenon in the industrialized nations of Europe, the United States and Japan. But developing countries are aging as well, and at a much faster rate than in the developed world.

Europe is still the “oldest” world region, while Africa the “youngest.” For many decades, Europe has had the highest proportion of population aged 65 and over among major world regions, and should remain the global leader well into the twenty-first century. However, Japan, with the highest life expectancy in the world, is projected to be the oldest country for the next several decades.

Elderly populations themselves are aging. An increasingly important feature of society aging is the progressive aging of the population itself. In the future, we can expect to see a sustained high growth rate of the oldest old. Between 1960 and 2040, all central and northern European countries are projected to experience an increase of at least 200 percent in the numbers of those 80 years and over, rising to over 400 percent in Switzerland and over 600 percent in Finland. However, even this rate “is dwarfed by that anticipated in the non-European countries, which is projected at a minimum of around 500 percent in New Zealand, over 800 percent in the United States, over 900 percent in Australia, and over 1,300 percent in Japan” (OECD, 1996, p. 15).

The Changing Age Structures of Societies: From Pyramids to Rectangularization

Population aging is altering the age structures of nations around the world. Age structures—representing age cohorts of different sizes relative to one another as they move through historical time—has profound implications for the economic, political, and social well-being of a nation and its people. The shape of an age structure tells much about dependency relationships between individuals and families, and their government, and the economic and social resources that may be available to meet the needs of the elderly. Figure 1.3 illustrates the historical and projected aggregate population age structure transitions in developing and developed countries.

Consider how much the age structures of populations in developed countries have changed over the past hundred years. At one time, most if not all countries had a youthful age structure similar to that of developing countries as a whole, with a large percentage of the entire population under the age of 15. In nineteenth-century America, for example, the shape of the population structure by age was that of a pyramid, with a large base (represented by children under age five) progressively tapering into a narrow group of those aged 65 and older. This pyramid shape has characterized the population structure by age in most human societies on record, from the dawn of civilization through the early Industrial Revolution and into the early twentieth century (Laslett, 1976; Myers, 1990). But by 1990 the age pyramid for America and other industrialized societies had come to look more like an irregular triangle.

Even as recently as 1950, among developed countries there was relatively little variation in the size of five-year groups between the ages of 5 and 24. The beginnings of the post-World War II baby boom can be seen in the 0-4 age group. By 1990, the baby boom cohorts were aged 24-44, and younger cohorts were becoming successively smaller. If fertility rates continue as projected through 2030, the aggregate pyramid will start to invert, with more weight on the top than on the bottom. The size of the oldest-old population (especially women) will increase, and people aged 80 and over may eventually outnumber any younger five-year-old group.

In OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) nations, between 1960 and 2000 there was a sharp decline in the age group 0-14 and a considerable increase in the older age groups (66-79 and 80+). For example, in Spain the percentage of those 0-14 decreased from almost 28 percent of the total population in 1960 to only about 16 percent in...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Global Aging and the Challenge to Families

- Part 1 Theoretical Perspectives

- 2 Theories about Families, Organizations, and Social Supports

- 3 From Family Groups to Personal Communities

- 4 Grandparents and Grandchildren in Family Systems

- 5 Older People and Family in Social Policy

- Part 2 Theoretical Perspectives

- 6 Intergenerational Transfers in the Family

- 7 Family Characteristics and Loneliness among Older Parents

- 8 Disposable Children

- Part III Intrasociety Diversity in Intergenerational Support

- 9 Israeli Attitudes about Inter Vivos Transfers

- 10 Social Network Structure and Utilization of Formal Public Support in Israel

- 11 Family Transfers and Cultural Transmissions Between Three Generations in France

- Part IV Intrasociety Changes in Intergenerational Support

- 12 Changing Roles of the Family and State for Elderly Care

- 13 Intergenerational Relationships of Japanese Seniors

- 14 “Modernization” and Economic Strain

- Part V Intra- and Intersociety Differences and Social Change

- 15 Family Norms and Preferences in Intergenerational Relations

- 16 The Role of Family for Quality of Life in Old Age

- 17 Ethnic and Cultural Differences in Intergenerational Social Support

- 18 Challenges of Global Aging to Families in the Twenty-First Century