- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Children of violence need to be heard. Unable or unwilling to verbalize their suffering, abused children are often immobilized by fear, rage, guilt, and pain. In the second edition of Breaking the Silence: Art Therapy with Children from Violent Homes , Cathy Malchiodi demonstrates the unique power of art therapy as a tool for intervening with children from violent backgrounds. In this new edition, she describes the intervention process from intake to termination, noting the complex issues involved at various levels of evaluation and interpretation. Bringing her years of experience in working at battered women's shelters to bear on the subject, Ms. Malchiodi brings the language of art therapy to life--a language of art that gives children a voice and those who work with them, a way of listening. The emphasis here is on the short-term setting where time is at a premium and circumstances are unpredictable. It is within this setting that mental health practitioners often experience frustration and a sense of helplessness in their work with the youngest victims of abusive families. Since the first edition of this book was published, research has led to some new ideas related to sexual abuse. The author analyzes several issues concerning the treatment of sexually abused children and art expressions of sexually abused children. In addition, Ms. Malchiodi launches a discussion about the ethical issues in the use of children's art as a whole. Featured throughout the book are 95 drawings by abused children. These drawings are at once poignant and hopeful, clearly representing the extraordinary suffering that abused children experience at, at the same time, showing that they can be reached. Because the practice of art therapy methods has been integrated into many disciplines, the final chapter covers development of art therapy programs for children. The author shares information on art supplied, space, and storage ideas. For art therapists, social workers, and other practitioners who work with children in crisis, this book presents a practical methodology for intervention that fosters the compassion and insight necessary to reveal what words cannot.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Breaking the Silence by Cathy Malchiodi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Role of Art Therapy in the Assessment and Treatment of Children from Violent Homes:

An Overview

Domestic Violence, Children, and Art Therapy: Some Personal Observations

During recent years, the area of domestic violence has received a considerable amount of attention from the government, mental health professionals, medicine, and the public. Child abuse, a component of family violence, has had the longest tradition of study and research (Finkelhor, 1979), going back to Henry Kempe’s identification of the “battered child syndrome” (Kempe, Silverman, Steele, Droegemueller, & Silver, 1962). It was not until the mid-1970s, however, that domestic violence became a growing issue among mental health professionals and only in recent years that the problem of abuse and violence among family members has emerged as a major focus of both intervention and research.

It is now known that violence in the home is a frequent occurrence (American Psychological Association, 1994). At least 2 million American women a year are battered by their partners; in addition, violence can occur in same sex relationships, although it is more common for women to be battered by men. It is also estimated that approximately 10 million children in the United States are exposed to wife abuse each year (Straus, 1991). These children are known to be at increased risk for abuse to themselves from their parents or guardians as well as emotional, cognitive, and behavioral problems throughout their lives. However, despite a growing understanding of domestic violence and its effects on children, the impact of domestic violence on children is still not well understood. Professionals who work with troubled families continue to look for ways to treat domestic violence and child abuse, understand its effects, and prevent its recurrence.

To complicate matters, children from violent homes come from diverse backgrounds and bring unique experiences to treatment. They may have been physically abused, neglected, sexually abused, and/or witnesses to violence to other family members. Moreover, although violence within the family structure may be defined as any interaction that involves a use of physical force against another family member, it can also include psychological maltreatment and emotionally cruel child-rearing practices. Additionally, children who live in violent homes may have experienced other types of family dysfunction including alcoholism or chemical dependency and mental illness. Lastly, family dysfunction may be acute or chronic; violence may have occurred over many years or may have been triggered by a recent stress to the family system.

Children are often the victims of violence in the home because family violence often involves an abuse of power in which a more powerful individual takes advantage of a less powerful one. Finkelhor (1979) observes that abuse tends to gravitate toward the relationships that offer the greatest power differential. This is acutely true in situations of incest or sexual abuse in which an older person may dominate a younger one; in family violence, a mother may abuse a young child or a husband may beat his wife.

From a cultural perspective, children may be exposed to violence not only in the home but also in society. Gil (1979) believes that family violence is a result of societal violence and thus cannot be viewed in isolation from society. He describes “structural violence” as conditions that exist in society that limit development and obstruct human potential. Structural violence might include poverty, discrimination, and unemployment; these, in turn, may also cause the eruption of personal violence in the home in reaction to the stress and frustration society has helped create. Jaffe, Wolfe, and Wilson (1990) also note that rock videos, violent sports figures, popular movies, and television may also contribute to an increase in societal violence and have an impact on violent behavior in children, particularly those who have been exposed to violence in their homes.

Since every child comes with a different set of dynamics, social factors, and coping mechanisms, every child perceives family violence in a different way, even though the circumstances of trauma may be similar. Many children will maintain incredible allegiance to their abusers, despite the horror of their experiences; others may react with ambivalence, simultaneously angry at and protective of the abusing parent. For these reasons alone, assessing and making appropriate treatment available to children from violent families is complicated at best.

To make sense of the diverse experiences of these children, I looked for a theme in their experiences that could help me to design therapeutic interventions through art experiences and understand what these children were saying through their expressions. When looking for a way to structure what I wanted to accomplish with these children, I found that crisis was the common denominator within the varied constellation of characteristics. Whether the child is in crisis because of violence in the home, to his mother, or to himself or herself, or in crisis simply because of having to leave familiar surroundings, a factor disturbing the equilibrium of the family brought the mother and her children to seek refuge and support. It was around this theme of crisis then that I developed theories of how to practice art therapy in a shelter environment with children from violent homes.

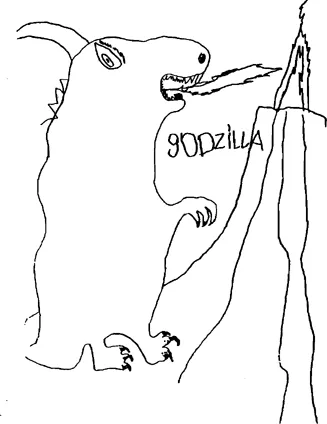

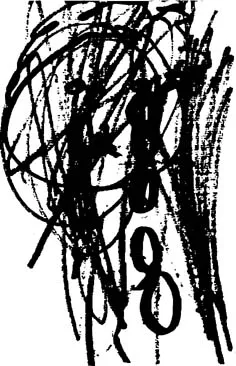

More than fifteen years ago when I first started to work with the children of battered women, I was profoundly struck by another commonality among these children: a visual metaphor of monsters (Malchiodi, 1982) in their art expressions. Often the metaphor was literally represented by the depiction of a monster of some sort (Figure 1-1). Other times the “monster” (Figure 1-2) was veiled in less literal, but equally powerful expressions of pain, anger, fear, or loneliness. These are the invisible monsters that gnaw away at the inner self, creatures that destroy self-esteem and leave in their wake anxiety and pain. For children from violent homes, the monsters can be an abusive parent, neglect, incest, and severe emotional trauma.

Figure 1-1. Monster drawing by a six-year-old boy at a battered women’s shelter (pencil, 8½″ × 11″).

Figure 1-2. Drawing by a seven-year-old boy at a battered women’s shelter (felt marker, 8½″ × 11″).

When I began to work with these children and their “monsters,” I also sensed there were some other commonalities in their visual communications. I began to realize that the complexity of each child’s situation contributed to the form and content of his/her expressions. Situations could include not only emotional trauma but also physical or sexual abuse, psychological maltreatment, chronic stress, and neglect. Family interactional systems might present addictions, serious mental illness, or even involvement in cults and bizarre life-style practices.

Historically, visual art has been used to make sense of crisis, pain, and psychic upheaval. Human suffering has inspired some our greatest art. Anyone who has viewed Picasso’s powerful painting of the effects of war on the Spanish town of Guernica is aware of the power visual imagery has in depicting trauma, violence, and acts of aggression. With reference to this work of art, Rollo May observes that “art is an antidote for violence” (1985, p. 215). He sees art expression as giving one a feeling of transcendence that might otherwise become negative outcomes such as drug addiction, suicide, and, on a societal scale, possibly warfare. May notes the preventive aspects of art expression, attributing to it the capacity to neutralize violence by taking the “venom” out of it. For these reasons, art therapy, a treatment modality that utilizes art expression as its core, has a unique role in the amelioration of violence and its effects. The very nature of image making makes it a powerful means of illicting and dissociating painful and frightening images from the self.

There is precedent for the use of art expression in helping individuals to express crisis and trauma through imagery (Golub, 1985; Greenberg & van der Kolk, 1987). Aside from the therapeutic benefit of nonverbal communication of thoughts and feelings, one of the most impressive aspects of the art process is its potential to achieve or restore psychological equilibrium. This use of the art process as intervention is not mysterious or particularly novel; it may have been one of the reasons that humankind developed art in the first place—to alleviate or contain feelings of trauma, fear, anxiety, and psychological threats to the self and the community (Johnson, 1987).

Like many art therapists, I have often utilized art to understand and make sense of trauma in my own life. Art expression has been the key to my understanding of personal loss, crisis, and emotional upheaval when words could not adequately express or contain meaning. However, the value of the art expression for me under these circumstances has not only involved the resultant images but also my immersion in the creative process. In essence, it has helped me to break through feelings to which I have been clinging and make new discoveries about myself (Malchiodi & Cattaneo, 1988). As aptly described by May (1985), “In all creativity, we destroy and rebuild the world, and at the same time we inevitably rebuild and reform ourselves” (p. 144).

Miller (1986), author of contemporary studies on child abuse, notes the connections between childhood trauma, such as abuse, and creative activity. She observes from her own experiences with visual expression that repressed feelings resulting from early childhood trauma take form in the works of artists and poets. For children who have been abused or have witnessed violence in their homes and are often silent in their suffering, art expression can be a way for what is secret or confusing to become tangible.

Miller also speaks strongly to the value of process in working through feelings through art as she explored the experiences of her childhood:

The repressed feelings of my childhood—the fear, despair, and utter loneliness—emerged in my pictures, and at first I was all alone with the task of working these feelings through. For at that point I didn’t know any painters with whom I would have been able to share my new found knowledge of childhood, nor did I have any colleagues to whom I could have explained what was happening to me when I painted. I didn’t want to be given psychoanalytic interpretations, didn’t want to hear explanations offered in terms of Jungian symbols. I wanted only to let the child in me speak and paint long enough for me to understand her language. (p. 7)

For a traumatized child, art expression may focus on the effects of violence as well as the situational factors causing dysfunction. Through the art product, the child does not necessarily focus on only one aspect of family violence but rather on a whole constellation of feelings and experiences. Art products, because of their nature, can simultaneously encompass the many complex, contradictory, and confusing feelings the child from a violent home may have. For a child, art can be anything the child wants or needs it to be. It can be cruel, horrifying, and destructive because in art expression there are no restrictions and such imagery is acceptable.

Art Therapy and Domestic Violence: Contemporary Perspectives

My experience as an art therapist with children from violent homes has come largely from direct involvement with children at battered women’s shelter programs. I was asked to provide intervention because the shelter staff often found solely verbal methods of interview and treatment unproductive and frustrating to these children in crisis. Because these children would not or could not verbalize their experiences, it was thought that more expressive methods of therapy could help them to relate the psychic and physical trauma of domestic violence.

However, in 1980, when I first started to work as an art therapist in a domestic violence shelter for women and their children, there were few role models available to guide my work within such a facility. It was not until many years later that I came across the work of Clara Jo Stember who performed a similar function while employed by the Connecticut Sexual Abuse Treatment Team in the 1970s. Stember, an art therapist, wrote a landmark article (published in 1980) that outlined her approach to art therapy with sexually abused children and their families. Most important, she strongly supported the integration of art therapy into such a treatment program with the art therapist serving as an important team member in both therapy and diagnosis. Unfortunately, Stember died in 1978, but she left the field of art therapy a rich legacy of her clinical applications to abused children.

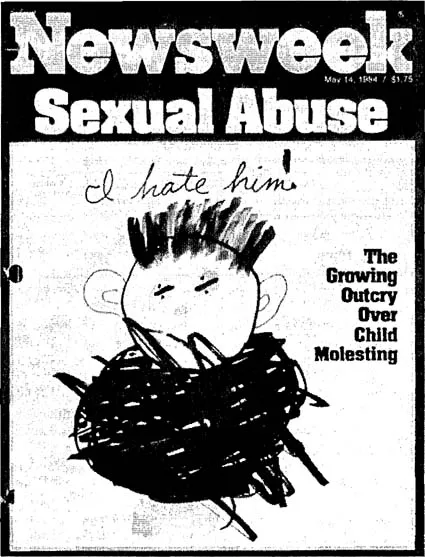

Instinctively, the public has long recognized and acknowledged the power of art expressions of children from violent homes. For example, on the cover of the May 14, 1984 Newsweek (Watson, Lubenow, Greenberg, King, & Jenkin, 1984), a special feature on sexual abuse is illustrated by the drawing of a child sexually victimized by her grandfather (Figure 1-3). The drawing is an extremely dramatic example of how the pain of a molested child can be depicted through a visual art modality. It succinctly and effectively portrays the complex feelings of anger, anxiety, and frustration associated with the trauma of sexual abuse. It does not take vast quantities of clinical knowledge to comprehend this child’s response to her experiences, but not all art expressions by children who are subjected to abuse are so easily deciphered. However, the power of visual expression with such children is undeniable.

Figure 1-3. Cover of Newsweek magazine featuring special issue on child sexual abuse.

Art therapists, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and other mental health professionals have become increasingly intrigued with the possibilities that art expression has for children from violent homes in both assessment and treatment. Because of the creative and dynamic nature of art expression, there is a great attraction to utilizing it in the treatment of the effects of domestic violence and child abuse. However, there continues to be relatively little written on this vital and important topic. Many clinicians are not well versed in the practice and discipline of art therapy and have groped with the use of art therapy in treatment of this child population. Most are interested in art expression solely for diagnostic purposes, and thus the distinction between diagnostic art techniques used with abused children and the practice of art therapy has become confused. This is especially evident in sexual abuse and domestic violence conferences and training symposia where social workers, legal experts, and other professionals mistakenly describe any use of art with children as art therapy.

The literature often indicates a misunderstanding and lack of depth concerning the use of art therapy in such situations. For example, Blick and Porter (1988) have discussed the use of what they term “arts therapy,” which apparently refers, at least in part, to the field of art therapy. One of their primary rationales for utilizing such a therapeutic modality in treatment is vaguely labeled as “fun.” Granted, art expression can be pleasurable, but such rationale detracts from the unique possibilities the modality has to offer this population and places the goals of art therapy in the realm of recreation and diversion. When the theoretical and clinical applications of art modalities are not clearly understood, they are often relegated to a subordinate status of leisure-related, adjunctive-type therapy.

Conerly (1986) advocates the use of art materials with sexually abused children but notes that possibilities for using them are limited because they can be messy and are difficult to transport if itinerant. Clinicians who may not have had substantial formal training or experience with art therapy methodologies are often uncomfortable with artistic media and dismiss their potentials because they do not know about them. They are generally unaware of the variety of possibilities that different art media have in accessing images and in enhancing the therapeutic session.

The professional who is unfamiliar with the theory and application of art therapy may see it as a tool for the child from a violent home to express hidden feelings and release hostilities through cartharsis. Thus, it may be viewed as a neutral outlet for the expression of repressed anger (Kramer, 1971). Although this use may provide a temporary remedy for overwhelming emotions, there are deeper, more substantial uses of art therapy.

Within the fields of art therapy, creative arts therapies, and play therapy, there has been greater and more serious progress in defining the scope of practice with children from violent homes. These disciplines have long been aware of art therapy’s special role in accessing images and memories of trauma, particularly with children. Clara Jo Stember (1978, 1980) was cognizant of these possibilities and was in the forefront of the application of art therapy specifically to abused children. Since her initial work in this area, many art therapists; dance, drama, and music therapists; and play therapists have explored and expanded the use of art making with children who have been exposed to violence.

Naitove (1982), an art therapist, extended Stember’s concepts, further supporting the use of art therapy in treatment and assessment of children who are physically or sexually abused. Naitove goes beyond the use of visual art in therapy, discussing the modalities of drama, poetry, movement, music, and sound. She identifies these therapies as providing swift and dynamic access to important information and rehabilitation. She also supports the concepts of Stember’s approach, giving add...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter One The Role of Art Therapy in the Assessment and Treatment of Children from Violent Homes: An Overview

- Chapter Two Working with Children from Violent Homes

- Chapter Three Art Evaluation with Children from Violent Homes

- Chapter Four Art Intervention with Children from Violent Homes

- Chapter Five Child Sexual Abuse

- Chapter Six Developing Art Therapy Programs for Children from Violent Homes

- Epilogue

- Resource List

- References

- Name Index

- Subject Index