![]()

1

The Nature of Perceived Social Support: Findings of Meta-Analytic Studies

Mary E. Procidano

Fordham University

Early conceptualizations of social support as being of direct benefit to psychological adjustment (Antonovsky, 1974; Caplan, 1974), and expectations that social support might interact with or buffer the effects of stress (e.g., Cobb, 1976; Rabkin & Struening, 1976), have led to the development and utilization of several social support measures, and to a concomitant refinement of our definition of social support. According to Barrera (1986), it is accepted widely that “social support” itself is a “meta-construct” (p. 413), consisting of social embeddedness, supportive transactions, and subjective appraisal, or perception, of support (Sarason, 1988; Vaux, 1987). Most available instruments purport to measure one or more of these particular constructs. This chapter is based mostly on a compilation of meta-analytic data relevant to the validity of measures of perceived social support from family (PSS–Fa) and from friends (PSS–Fr) that were originally developed and validated on college students (Procidano & Heller, 1983). This information is intended to contribute to our growing understanding of the perceived social support construct, and to document the utility of the PSS measures.

There are different rationales and benefits associated with assessing each of the three widely recognized support constructs. Hirsch and Rapkin (1986) stated that social embeddedness, or social network characteristics, although virtually always assessed via subjects’ self-reports, is believed to possess ecological validity in reflecting peoples’ “personal communities” (p. 395). Network characteristics, such as size and presence of family members and friends, have been found to correlate with adjustment but often have no direct or stress-buffering effect on symptomatology. Furthermore, knowing structural characteristics of individuals’ support networks does not help to clarify the processes by which supportive transactions occur and consequently might aid in coping and adjustment (Barrera, 1986; Cohen & Wills, 1985).

Assessing supportive transactions also is believed to have particular advantages. Again, virtually always obtained via self-report, as opposed to behavioral observation (Barrera, 1986), this type of measure affords specificity and precision in delineating the supportive functions that network members might serve, by “gauging the responsiveness of others in rendering assistance when subjects are confronted with stress” (p. 417). The most widely used measure of supportive behaviors, the Inventory of Socially Supportive Behaviors (ISSB; Barrera, Sandler, & Ramsay, 1981), has been found to reflect meaningful categories of supportive transactions (Barrera & Ainlay, 1983; Stokes & Wilson, 1984; Walkey, McCormick, Siegert, & Taylor, 1987). However, the expectation that such specificity would aid in the prediction of positive adjustment to stress has generally not received empirical verification (e.g., Cohen & Wills, 1985; Sandler & Barrera, 1984; Tetzloff & Barrera, 1987). One explanation for this lack of confirmation is that behaviors that are designated a priori as supportive may not be subjectively desirable to the recipient, perhaps because they are performed begrudgingly, or by persons not otherwise perceived as supportive. At issue is the distinction between overt behaviors performed by social network members and their subjective impact on the recipient.

The PSS–Fa and PSS–Fr scales (Procidano & Heller, 1983) were designed to assess such subjective impact, guided in part by theoretical statements regarding the nature and potential outcomes of social support. Cobb (1976) described social support as “information leading the subject to believe that he is cared for and loved … esteemed and valued … and belongs to a network of communication and mutual obligations” (p. 300). Similarly, Cassel (1976, p. 107) used the term feedback in describing social support. This cognitive or attributional definition of social support is also consistent with current conceptualizations of coping as including an appraisal component (e.g., Folkman, Schaefer, & Lazarus, 1979). The PSS measures are composed of 20 declarative statements each, regarding the extent to which subjects believe that their needs for support, information, and feedback (Caplan, 1974) are being fulfilled by family or friends, respectively. Each instrument includes some items reflecting provision of support by the subject to others, consistent with findings of a relationship of reciprocity and bidirectional support-provision to adjustment (Maton, 1987; Tolsdorf, 1976). Original validation studies with college students (Procidano & Heller, 1983) indicated that the measures reflected related but separate constructs. This differentiation has been supported by Sarason and her colleagues (B. R. Sarason, Shearin, Pierce, & Sarason, 1987), who found different patterns of correlations for the two scales.

Additional empirical evidence is available to indicate the particular advantages associated with assessing perceived social support. Perceived support has been found to correlate with social-network characteristics (Procidano & Heller, 1983; Stokes, 1983; Vaux & Athanassopoulu, 1987; Vaux & Harrison, 1985) and with supportive transactions (Vinokur, Schul, & Caplan, 1987; Wethington & Kessler, 1986). It has been suggested that the beneficial influence of received support is mediated by perceived support (Wethington & Kessler, 1986). Many investigators have found that, compared to social embeddedness and receipt of supportive transactions, subjective appraisal of support is more likely to predict well-being and/or to buffer stress (e.g., Barrera, 1986; Wethington & Kessler, 1986; Wilcox, 1981). Consistent with the original speculations regarding the nature of social support (Caplan, 1974; Cassel, 1976; Cobb, 1976), Sarason and her colleagues (B. R. Sarason et al., 1987) concluded recently that, essentially, social support involves the feeling “that we are loved and valued, that our well-being is the concern of significant others” (p. 830). Of the three social-support constructs, perceived support seems closest to this definition (I. G. Sarason, 1988).

The principal argument against such measures is that they may be confounded with other variables, particularly antecedent adjustment and stress (e.g., Barrera, 1986; Eckenrode & Gore, 1981). The specific rival hypotheses are: (a) that the apparently beneficial effects of support may be attributable to individual difference variables, such as social competence (Procidano & Heller, 1983); (b) that the negative association of social support to symptomatology may be attributable to conceptual overlap between the two construct domains (e.g., Dohrenwend, Dohrenwend, Dodson, & Shrout, 1984); and, (c) that the apparent stress-buffering or interaction effect of support may be an artifact of its correlation with stress measures, such that stress by support interaction terms are not composed of independent components.

The available responses to these concerns are incomplete. First, it still is unclear to what extent antecedent personality characteristics contribute to variance in social support or, more seriously, account for its apparent effects. Cutrona (1986), for instance, found that network characteristics accounted for only about 30% of the variance of perceived support and suggested that future research examine other determinants of support perception, including personality characteristics. Regarding possible confounding of support with symptomatology, some evidence suggests that the two domains are distinct. Turner (1983) made such a conclusion on the basis of factor analytic studies. Vinokur et al. (1987) found in a longitudinal Study that perceived support was influenced by supportive transactions, as reported by social network members; but only “moderately” by subjects’ own negative outlook bias, and “weakly” by antecedent anxiety and depression (p. 1137). Procidano and Heller (1983) found, in an experimental study involving college students, that PSS–Fa was unaffected by positive or negative mood inductions, but PSS–Fr was lowered by a negative mood induction. Finally, Cohen and Wills (1985) investigated potential confounding between support and stress. After reviewing the available published studies that tested the buffering hypothesis, they concluded that the support by stress interaction was not an artifact of correlations between the two variables, because of the frequency with which the buffering effect still was observed in the absence of such a correlation.

More information is needed to help clarify the issue of confounding. There is still little consensus regarding the constructs to which support dimensions, including perceived support, “should” or “should not” be related. Thus, it is not surprising that Heitzmann and Kaplan (1988) observed that discriminant-validity information for social support measures is lacking. Barrera (1986) suggested a seemingly balanced approach to this matter, suggesting that “concern for confounding [might] discourage the scrutiny of legitimate relationships between social support concepts and measures of stress and distress” (p. 434).

The purpose of this chapter is to summarize reliability and validity information regarding the PSS measures across a reasonably wide range of populations. Some reviewers of social support instruments have commented that such data are very limited (House & Kahn, 1985; Tardy, 1985) but would be valuable in helping to clarify the nature and potential outcomes of social support (Heitzmann & Kaplan, 1988). Toward these ends, all available published and unpublished findings regarding the PSS measures were collected and submitted to several sets of meta-analyses. The inclusion of unpublished material minimizes the “file-drawer problem” in meta-analytic research, whereby the apparent magnitude of effects is inflated because nonsignificant results are less likely to be accepted for publication (Wolf, 1986). The findings were organized into categories relevant to specific aspects of reliability (internal consistency and test–retest) and validity (content, contrasted groups, and construct), as reflected in the current literature.

RELIABILITY

Internal Consistency

Estimates of the internal consistency of the PSS instruments were available for four samples, including college students (Ferraro & Procidano, 1986; Procidano & Heller, 1983), high school girls (Procidano, Guinta, & Buglione, 1988), and male multiple sclerosis patients (Louis, 1986). Cronbach alphas ranged from .88 to .91 for PSS–Fa and from .84 to .90 for PSS–Fr, and thus the instruments appear to be internally consistent.

Test–Retest Reliability

Test–retest reliabilities were available for four samples of subjects, including college students (Ferraro & Procidano, 1986), adolescents and adolescents with alcoholic fathers (Clair, 1988), and high school girls (Procidano et al., 1988). The test–retest reliabilities for PSS–Fa over a 1-month period ranged from .80 for high school girls to .86 for college students. The average correlation based on z transformations, as recommended by Wolf (1986), was .82. The reliability for PSS–Fr for the same period of time ranged from .75 for adolescent offspring of alcoholic fathers to .81 for adolescent offspring of nonalcoholic fathers (Clair, 1988), r = .79.

There was no evidence of testing effects (over a 1-month period) in the instruments. Pre-post comparisons (based on t tests for correlated means) of data from college students (Ferraro & Procidano, 1986) were nonsignificant for both PSS–Fa [t (112) = .41, n.s.] and PSS–Fr [t (112) = − .60, n.s.]. Results based on high school girls were similar: t (88) = .25, n.s., for PSS–Fa; and t (88) = .46, n.s., for PSS–Fr.

VALIDITY

Norms and Contrasted-Groups Validity

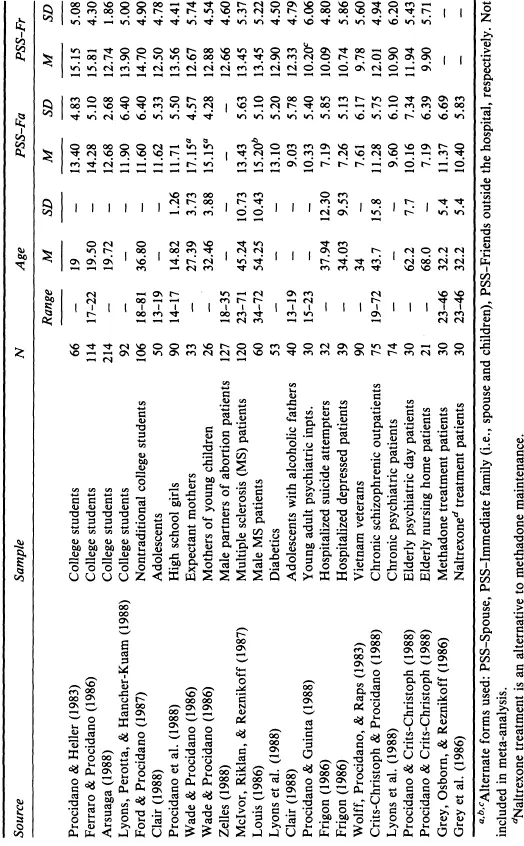

Table 1.1 provides normative information (means and standard deviations) of the PSS instruments for 24 samples. For the meta-analysis, the samples were categorized a priori as nonclinical or clinical (i.e., all or most subjects carrying diagnoses and/or receiving psychological or psychiatric treatment). There are 13 nonclinical samples (from Procidano & Heller, 1983, through Lyons, Perrotta, & Hancher-Kuam, 1988). Samples receiving medical treatment, including multiple sclerosis patients (Louis, 1986; Mclvor, Riklan, & Reznikoff, 1984) and diabetics (Lyons et al., 1988), were classified as nonclinical. As it was not clear whether or not Clair’s sample of adolescent offspring of alcoholic fathers should be considered clinical by virtue of the father’s status (as well as the possibility that the subjects themselves might be involved in treatment), or nonclinical, that sample was not included in the classification. The remaining 10 samples from Procidano and Guinta (1988) through Grey, Osborn, and Reznikoff, 1986, including the samples of Vietnam veterans (Wolff, Procidano, & Raps, 1983) and elderly nursing home patients (Procidano & Crits-Christoph, 1988), met the criteria for clinical status.

TABLE 1.1

Means and standard Deviations of PSS Measures

For PSS–Fa, means of the nonclinical samples ranged from 11.60 to 14.28, compared to 7.19 to 11.34 for clinical samples. The distributions of nonclinical versus clinical means approached each other but did not overlap. (Obviously, the same was not true of the respective distributions of scores.) Pooling all the nonclinical and clinical samples into two groups yielded a nonclinical grand mean of 12.70, compared to 9.25 for the clinical group. A comparison of these two groups was highly ...