![]()

1

Bridging the Gap

Using Mobile Devices to Connect Mathematics to Out-of-School Contexts

Sandra F. Sawaya and Ralph T. Putnam

Introduction

Mathematics educators have long been concerned that learners fail to connect the mathematics they learn in school to situations and problems outside the classroom (Boaler, 1993; Evans, 1999; Resnick, 1987). On one hand, learners too often fail to bring their school mathematics to bear in solving real-world problems; on the other hand, school instruction seldom builds on the informal knowledge and understandings that learners have developed through their out-of-school lives. In the past, teachers used word problems to build these connections, typically by simulating the mathematical problems and situations learners might encounter. Newer digital tools such as the Web, videos, and animations have provided access to real-world data and contexts for solving mathematical problems and supporting the learning of mathematics. These applications, however, largely remain confined within the classroom. With the mobility they afford, mobile devices create significant new opportunities for connecting the learning of mathematics to out-of-school and other meaningful contexts.

In this chapter, we consider how mobile devices, such as smartphones and electronic tablets, can bring out-of-school contexts and problems into the classroom for learning mathematics and take school mathematics into out-of-school contexts. We adopt the definition of mobile learning (m-learning) set forth by Crompton (2013, p. 4): “learning across multiple contexts, through social and content interactions, using personal electronic devices.” Although we offer examples of instructional activities, drawing on specific mobile devices and tools, our emphasis is on providing a framework for designing learning activities that support connections between school mathematics and out-of-school problems and contexts.

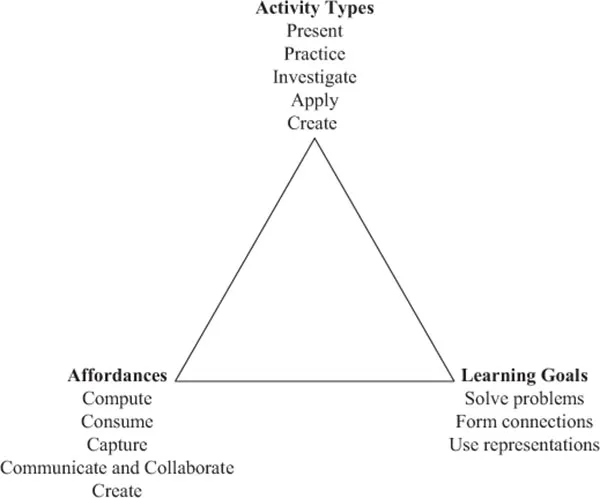

Figure 1.1 Representation of the framework for designing learning activities using mobile devices

We organize our consideration of how mobile devices can support meaningful mathematics learning with the framework in Figure 1.1. The framework depicts three broad issues to which we believe teachers or designers should attend when creating meaningful mathematical learning experiences involving the use of mobile devices: (a) mathematics learning goals, (b) learning activities in which learners will engage, and (c) affordances of the technology to be used—in this case, mobile technology. Because our focus is on how mobile devices can enhance mathematics teaching and learning, we begin by considering the affordances mobile technologies bring to mathematics learning, followed by a brief discussion of the mathematics learning goals we emphasize for bridging in- and out-of-school mathematics. We then use the idea of learning activity types (Harris & Hofer, 2009) to examine particular uses of mobile devices in mathematics instruction.

Affordances of Mobile Devices

In considering what mobile devices offer to support mathematics learning—more specifically, connecting classroom mathematics to out-of-school and meaningful contexts—we begin with the four “C”s of mobile devices for learning proposed by Quinn (2011): (a) computing input, (b) consuming content, (c) capturing surrounding context, and (d) communicating with other devices and individuals. From White, Booker, Ching, and Martin’s (2011) proposed practices with mobile devices, we expanded communicating to include collaborating with others and added (e) creating content.

Compute

Through what may be their most straightforward affordance, mobile devices allow learners to enter data and perform computations—to support their efforts in problem solving or to check their own computational work—by using built-in calculators or other applications. Clearly, these functions are available in numerous other tools such as calculators and desktop computers; mobile devices make them easily accessible when needed in many contexts.

Consume

Mobile devices can be used to access various types of information, such as websites, images, videos, and electronic books. This information can either be found stored in the device or can be accessed from the Web through a wireless connection. Again, mobile devices are unique in allowing learners this access to content just in time, at the time of need, or anywhere at any time.

Capture

A key affordance of mobile devices is their ability to capture content and experiences such as images and videos, audio, text, and location coordinates using a camera, microphone, keyboard, and Global Positioning System (GPS), respectively. The content can either be stored locally on the devices or uploaded to the cloud for access from anywhere at any time.

Communicate and Collaborate

Mobile devices also allow learners and teachers to share content they have accessed or captured—for example, by uploading content to the Web and sharing it on social networking sites. In addition, mobile devices allow learners to connect with other individuals and communicate synchronously via voice and video calls, asynchronously through text messages, and even through images and videos. Moreover, with their ability to capture content and synchronous (or sync) information, mobile devices can even communicate with other devices. Content captured on one mobile device can sync with or be instantly uploaded to the cloud and accessed from another mobile device or desktop. This connectivity also supports collaboration by learners working together on common documents or projects. There are many collaborative productivity applications (e.g., Google Drive) that support such interactions.

Create

Finally, mobile devices enable learners to create their own content and share it with others. Image and video editing applications and sketching tools are some examples of applications that allow learners to create content.

None of these affordances alone is unique to mobile devices; it is by bringing them together and providing easy access to them in multiple settings that mobile devices offer powerful tools for supporting learning.

Learning Goals

Considering the mathematics learning goals for students should arguably be the starting point for any instructional planning and is especially important for avoiding the technocentrism (Papert, 1990) of focusing more on what one can do with a particular technology than on the sort of learning that is intended. When considering mathematics learning goals for any particular instructional experience, it is important to consider both the mathematics content or topic—for example, whole-number addition, slope, or quadratic functions—and the ways learners are expected to engage with that content. Is the goal, for example, to increase fluency or a skill or procedure or to develop understanding of a concept? For K–12 mathematics, these two aspects of learning goals have been described by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) (2000) as Content Standards and Process Standards.

A number of these Process Standards are particularly relevant for the focus of this chapter—better connecting school mathematics and out-of-school contexts. As part of NCTM’s (2000) Problem Solving Standard, learners are expected to “build new mathematical knowledge through problem solving” and “solve problems that arise in mathematics and in other contexts” (p. 52). As part of the Connections Standard, they are expected to “recognize and apply mathematics in contexts outside of mathematics” (p. 60); for the Representation Standard, learners are expected to “use representations to model and interpret physical, social, and mathematical phenomena” (p. 67).

Learning Activity Types

Whereas learning goals represent the teachers’ desired outcomes for learners, classroom activities typically anchor a teacher’s instructional planning. It is through thinking about the learning or instructional activities that will constitute a lesson that the plan for teaching takes shape. Capitalizing on this central role of activities in instructional planning, Harris and Hofer (2009) developed the construct of learning activity types to help teachers think about incorporating new technologies into meaningful subject-matter instruction: “Learning activity types function as conceptual planning tools for teachers; they comprise a methodological shorthand that can be used to both build and describe plans for standards-based learning experiences” (p. 4089). In our framework, we consider five broad learning activity types that encompass much of current mathematics teaching practice: (a) presenting content, (b) practicing mathematical skills, (c) investigating and (d) applying mathematical problems, and (e) creating content.

In presenting the learning activity types, we explain each and provide examples from the scholarly literature illustrating how our framework of affordances, learning goals, and activity types can be used to develop learning activities to connect the mathematics learned in school to that observed in the real world.

Presenting

A central activity in most mathematics classes is presenting, explaining, or demonstrating mathematics content for students to consider. In a ubiquitous structure in K–12 mathematics classrooms, the teacher presents a new concept or procedure; learners then begin working with that concept or procedure through guided practice, followed by independent practice, often for homework. Traditional college mathematics classes typically consist largely of lecture or presentation of material by the instructor. Even in classrooms designed to be more learner-centered or individualized, presentation of content plays an important role. Mobile technologies can provide access to presentations and explanations of mathematics content in new settings and offer possibilities for enhancing and transforming presentations and the role they play in learning.

Accessing presented content in various settings. Mobile devices enable learners to access recorded teacher presentations or explanations, applets or other media demonstrating mathematical concepts, or a wealth of video- and print-based explanations of mathematical content. In the currently popular approach of flipped classrooms (e.g., Hamden, McKnight, McKnight, & Arfstrom, 2013) learners can access presentations and explanations during out-of-class time, making more problem solving, group work, and interaction during class time possible. For example, Franklin and Peng (2008) provided iPod Touches to eighth-grade students to promote the learning of algebraic equations. They asked the students to use the iPod Touches to watch mathematics anywhere and at any time.

This flexibility in when and where learners can access presented content can also support broader problem-solving or investigation activities by allowing learners to access needed content and explanations at the time of need while solving mathematical problems situated in the real world (more on this in the following sections).

Enhancing teacher presentations. Drawing on mobile devices’ ability to capture images, video, and other information, teachers can enhance their presentations by incorporating examples and data from real-world settings, making them more relevant and meaningful to learners. For example, teachers could use the video function of their mobile devices to record videos of processes—such as a cylindrical container being filled with water or of a child on a swing—and then superimpose a dynamic graph of the process. Examples of such “graphing stories” may be seen at http://graphingstories.com.

Learners contributing to presentations. To connect explanations even more to learners’ experiences, teachers can have learners capture data and information to be used in presentations and demonstrations. For example, an elementary teacher might send learners around the schoolyard to take photos of various rectangular objects to be used in a beginning consideration of area and perimeter.

To illustrate how mobile devices can enhance and transform presentations of mathematical content, we refer to the iOS- and Android-compatible application Aurasma (2014). Aurasma uses image recognition software and location-based services to detect images and scenes and superimpose media—auras—on them. Each trigger image, such as a painting in a museum or a sign on a street corner, will have its own aura. Auras can be noninteractive—for example, images, videos, or animations—or interactive—such as a website or three-dimensional (3D) representation that can be manipulated. Learners scan the original trigger image with their mobile device cameras or go to a specific location to activate the aura and view or interact with it on their screens, thus accessing presented content in particular contexts.

Teachers can set images or certain locations to trigger some form of presenting mathematical content. For example, teachers can create a video to explain the concept of monetary change and have it trigger when learners approach the school’s vending machine. To enhance a presentation on polygons, a teacher can take pictures of several square-shaped objects found in the real world and set those as auras that are triggered when learners scan a specific presentation slide. Conversely, the learners themselves can capture pictures of various polygons and create their own auras.

Practicing

Practicing various skills, procedures, and processes is important for developing the fluency essential for using and learning mathematics. Mobile devices can enhance practice activities both by increasing motivation and opportunities for practice and by providing more meaningful practice in the context of other mathematical activity.

Teachers have long turned to game-like activities to motivate drill and practice. Mobile devices provide many free or paid applications that allow learners to practice their mathematics skills anywhere at any time. The game-like nature of these applications may make the practice more motivating and engaging. For example, Kiger, Herro, and Prunty (2012) compared a traditional approach to mathematics drill and practice to its digital counterpart. Two groups of students were asked to practice their multiplication skills using either flash cards or using a Web application on an iPod Touch. The students who practiced using the mobile device scored significantly higher on a learning outcomes posttest.

Having practice activities accessible on mobile devices also enables connecting skill practice to meaningful contexts. For example, teachers could set up quick response (QR) codes or Aurasma image triggers so that students are prompted to practice skills or facts as part of a treasure hunt or scavenger hunt game. In addition, opportunities for practice can be provided as an integral part of broader investigativ...