![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE DEVELOPMENT OF ADAPTIVE EXPERTISE AND FLEXIBILITY: THE INTEGRATION OF CONCEPTUAL AND PROCEDURAL KNOWLEDGE

Arthur J. Baroody

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

In Hard Times (Ford & Monod, 1966), Charles Dickens described a teacher by the name of Mr. M’Choakumchild in order to satirize teachers trained to focus on memorizing facts by rote at the expense of all else:

He … had taken the bloom off … of mathematics.… He went to work … looking at all the vessels ranged before him.… When from thy boiling store [of facts] thou shalt fill each [vessel] brimful by-and-by, … thou … kill outright … Fancy [imagination, curiosity, creativity] lurking within—or sometimes only maim [it]. (p. 6)

Those interested in improving mathematics instruction have long been concerned about the ineffective, if not harmful, way traditional instruction promotes arithmetic expertise (e.g., Brownell, 1935; Davis, 1984; Erlwanger, 1975; Holt, 1964; Kilpatrick, 1985; Wertheimer, 1945/1959). Consider, for example, two vignettes with dramatically different outcomes.

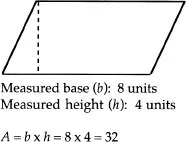

Vignette 1: A Case of Inflexible Mechanical Learning. Wertheimer (1945/1959) told of a visit he took to a classroom that had just learned how to determine the area of a parallelogram. The students had been taught to measure the length of a parallelogram’s base and height and multiply these two values (see Fig. A). After watching them successfully complete several “problems,” Wertheimer sought permission from the teacher to ask the class a question. Proud of his students, the teacher readily agreed. Wertheimer stepped to the board, drew a picture similar to the one in Fig. B and asked what its area was. Some students were “obviously taken aback. One pupil [noted]: ‘Teacher, we haven’t had that yet’” (p. 15). Other students tried to apply the procedure they had been taught but quickly became bewildered. In brief, confronted with a somewhat novel task, the students did not see how their school-taught procedure applied, leaving them utterly helpless.

Figure A: The school-taught procedure

Figure B: Wertheimer’s variation of the practiced task

Vignette 2: A Case of Flexibly Applied Learning. Arianne, a fourth grader, was attempting to divide 901 by 2 in order to solve a problem. Her initial effort (shown in Fig. C) resulted in an answer of 45 with a remainder of 1. Her teacher noticed that she spontaneously revised her answer (shown in Fig. D). Asked why she had changed her answer, Arianne explained that she had checked it. This process was described cryptically in a journal entry the girl recorded later: I had ansewer of 45R1. I added it together and didn’t get 901. So I added a zero and got 900 and added the 1.

Figure C: Arianne’s Initial Effort

Figure D: Arianne’s Revision

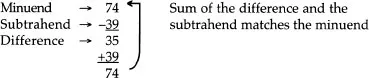

Several months earlier Arianne’s class had learned that subtraction could be checked by adding the answer (difference) to the subtracted amount (the subtrahend). If the resulting sum was the same number as the starting amount (minuend), then the answer was presumably correct. The teacher had used small numbers to illustrate the rationale for the procedure (e.g., subtracting 2 from 5 can be undone by adding 2) before demonstrating this checking procedure with multidigit examples like that shown as follows:

Without further instruction, Arianne applied the principle for checking subtraction to the task of checking her division. Instead of using the inverse operation of multiplication (2 × 45 = 90), she checked her answer informally by using its mathematical equivalent, namely repeated addition of a like term. (Adding 45 + 45 is what she meant by “I added it together and didn’t get 901.”) After recognizing that 45 could not be the correct solution and adding a 0 to make her answer 450, the girl proceeded to check her new answer in the following manner:

To check whether Arianne really understood the checking procedure for division she had invented, her teacher inquired, “What if we had divided by three?”

Arianne promptly indicated that she would have to add her answer three times.

“Or multiply by three,” interjected Alison who had been listening intently to the dialogue.

Note that because these students understood the rationale for checking subtraction, they recognized that, in principle, it could be applied to the related, but different, task of checking a division outcome. Moreover, their understanding allowed them the flexibility to adapt their learned procedure so that i t could be used in this new context.

Vignette 1 illustrates what Giyoo Hatano (1988) called “routine expertise,” knowledge memorized by rote, knowledge that can be used effectively with familiar tasks but not with novel ones, even those that differ only slightly from familiar ones. Vignette 2 illustrates what he called “adaptive expertise,” meaningful knowledge that can be applied to unfamiliar tasks as well as familiar ones. In contrast to rote knowledge, which is learned and stored in isolation, meaningful knowledge is learned and stored in relation to other knowledge. That is, it is grasped and represented in connection with other knowledge (Ginsburg, 1977; Hiebert & Carpenter, 1992). If meaningful knowledge is the basis of adaptive expertise (the flexible application of knowledge) and can be characterized as well-connected knowledge (e.g., Ginsburg, 1977; Hiebert & Carpenter, 1992; Hiebert & Lefevre, 1986), then the construction of well-connected knowledge should be the basis for fostering adaptive expertise or flexibility, as measured by transfer (e.g., understanding new subject matter or inventing a strategy or procedure to solve a novel problem). Analogously, the acquisition of unconnected knowledge should be the basis for promoting routine expertise or inflexibility.

This chapter begins with a historical sketch of the debate about the developmental relations between conceptual and procedural knowledge. Tentative theoretical conclusions about these relations are then outlined. Finally, key implications of these conclusions for current reform efforts are discussed. The aim of this chapter is to provide a general framework for understanding the significance of the chapters that follow and for further explorations of the development of arithmetic concepts, procedures, and adaptive expertise.

Historical Perspective

Researchers interested in the teaching and learning of arithmetic have long distinguished between knowledge memorized by rote and knowledge acquired meaningfully. The former has been equated with computational skill or procedural knowledge; the latter, with understanding or conceptual knowledge. In this section, the early and then the more recent view of this dichotomy are examined.

EARLY VIEWS: SKILL VERSUS UNDERSTANDING

Resnick and Ford (1981) pointed out that “the relationship between computational skill and conceptual understanding is one of the oldest concerns in the” field of mathematical psychology (p. 246) and that, in the past, the focus was on which was better. In 1935, William A. Brownell outlined three views of arithmetic learning, each of which reflected different assumptions about the importance of computational skill and understanding. After briefly describing these views, we summarize the early skills versus concepts debate.

Three Theories of Arithmetic Learning

In the early 20th century, the following three theories of arithmetic teaching and learning were prominent in the United States: drill, meaning, and incidental-learning theory (Brownell, 1935; cf. Cowan, chap. 2, this volume).

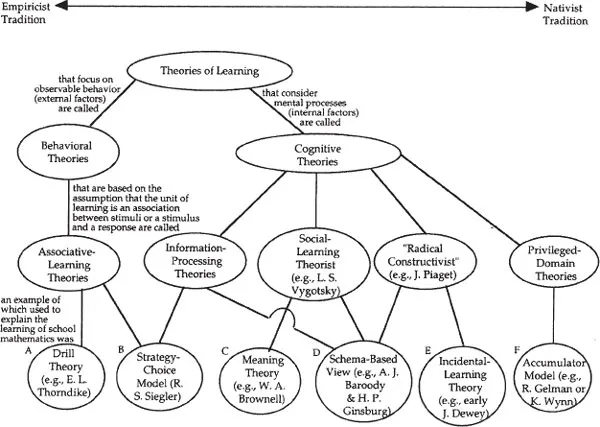

Drill Theory. According to drill theory (Model A in Fig. 1.1), a product of associative theories of learning, instruction should focus on ensuring the (rote) memorization of computational skills (see Cowan, chap. 2, this volume, for a detailed discussion). The basic assumptions of this theory were (a) children must learn to imitate the skills and knowledge of adults, (b) what is learned are associations or bonds between otherwise unrelated stimuli, (c) understanding is not necessary for the formation of such bonds, and (d) the most efficient way to accomplish bond formation is through direct instruction and drill. In this view, the learning of single-digit (basic) number combinations such as 5 + 3 = 8 and multidigit renaming procedures such as “carrying” or “borrowing,” for example, could be achieved quickly by a well-organized regimen of instruction and practice (Thorndike, 1922). Self-invented procedures by children, such as counting- or reasoning-based computational strategies (e.g., Arianne’s procedure for checking division described earlier) were viewed as impediments (see, e.g., Smith, 1921; Wheeler, 1939).

Figure 1.1: The Psychological Roots of Various Theories of Arithmetic Learning

Meaning Theory. Dissatisfaction with traditional mathematics instruction and its theoretical basis (drill theory) led Brownell (1935) to propose meaning theory (Model C in Fig. 1.1). This theory is akin to the social-learning theory of Lev S. Vygotsky (1962) and foreshadowed Hatano’s (1988) ideal of adaptive expertise. In Brownell’s view, instruction should focus on promoting the meaningful memorization of skills:

The “meaning” theory conceives arithmetic as a closely knit system of understandable ideas, principles, and processes. According to this theory, the test of learning is not mere mechanical facility in “figuring.” The true test is an intelligent grasp upon number relations and the ability to deal with arithmetical situations with proper comprehension of their mathematical as well as their practical significance. (p. 19)

According to meaning theory, teachers must take into three interrelated factors in order to promote the learning of arithmetic with understanding:

• The complexity of arithmetic learning. In the traditional drill approach, for instance, instruction on counting and numbers is followed by drill of “number facts.” This approach “almost totally neglects the element of meaning and the complexity of the first stage in arithmetic learning” (Brownell, 1935, p. 21). According to meaning theory, children are, at first, expected to engage in “immature” strategies, such as self-invented counting and reasoning strategies (see, e.g., Baroody, 1987b, 1999). These informal methods provide the basis for mature knowledge, including mastery of basic number combinations, understanding of arithmetic principles, and meaningful memorization of multidigit procedures (see also, e.g., Ambrose, Baek, & Carpenter, chap. 11, this volume; Baroody, 1987a; Cowan, chap. 2, this volume; Fuson & Burghardt, chap. 10, this volume).

Brownell (1935) noted that children may initially need to rely on countingbased arithmetic strategies because such strategies may be their only meaningful means of operating on numbers. As soon as they are ready, however, students should be encouraged to use more advanced strategies, such as reasoning (e.g., strategies transforming an unfamiliar problem into a familiar one: 7 + 5 = [7 + 3] + [5 − 3] = 10 + 2 = 12). Eventually, children come “to a confident knowledge of [a number combination], a knowledge full of meaning because of its frequent verification. By this time, the difficult stages of learning will long since have been passed, and habituation occurs rapidly and easily” (p. 24). Drill may serve to increase the facility and permanence of recall. In sum, “children attain [skill] ‘mastery’ only after a period during which they deal with [arithmetic] by procedures less advanced (but to them more meaningful) than automatic responses” (Brownell, 1941, p. 96).

• Pace of instruction. In the drill approach, children are told or shown, for instance, a “number fact” once or twice and expected to memorize it quickly (within a week), if not almost immediately (a day or so). According to meaning theory, children are not expected to imitate immediately the skill or knowledge of adults. Learning arithmetic—including mastering the basic number combinations and multidigit procedures—is viewed as a slow, protracted process. In the meaning approach, then, time is allowed for children to construct an understanding of arithmetic ideas and to discover and rediscover arithmetic regularities before practice makes the basic number combinations automatic. The result is a more secure knowledge of these combinations, knowledge that is more easily transferred.

• Emphasis on relations. According to drill theory, for example, 6 + 5 = 11 and 7 + 4 = 11 should not be taught simultaneously because of “associative confusion” or “associative interference.” Brownell (1935) argued that addition and subtraction combinations such as 3 + 2 = 5 or 5 − 3 = 2 are not facts but generalizations and, for teaching purposes, should be treated as such. To help children make such generalizations, teachers need to help them discover a regularity such as 3 + 2 = 5 many times in many different situations. Furthermore, they should help students see the relations among combinations so that they came to know the basic combinations as a system of knowledge.

Incidental-Learning Theory. Incidental-learning theory (Model E in Fig. 1.1), an analog of Jean Piaget’s (radical) constructivist theory, was embodied in John Dewey’s early progressive-education movement. This theory was also a reaction to drill theory. According to this view, children should be free to explore the world around them, notice regularities (patterns and relations), and actively construct their own understanding and procedures. In other words, mathematical learning should be the incidental result of satisfying their natural curiosity.

Brownell (1935) concluded that the incidental-learning approach was impractical for three reasons. The first is that “incidental learning, whether through ‘units’ or through unrestricted experiences, is slow and time-consuming. [A second is that the] arithmetic ability as may be developed in these [unfocused] circumstances is apt to be fragme...