- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

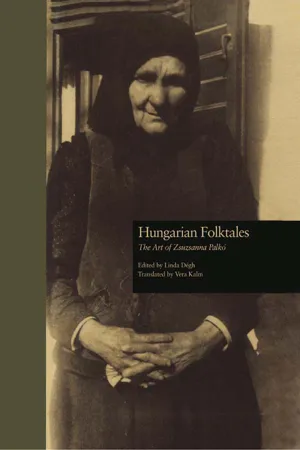

First published in 1996. There has been no more important relationship between folk artist and folklorist than that between Zsuzsanna Palkó and Linda Dégh. Dégh's painstaking collection of Mrs. Palkó's tales attracted the admiration of the Hungarian-speaking world. In 1954 Mrs. Palkó was named Master of Folklore by the Hungarian government and summoned to Budapest to receive ceremonial recognition. The unlettered 74-year-old woman from Kakasd had become "Aunt Zsuzsi" to Linda Dégh—and was about to become one of the world's best known storytellers, through Dégh's work.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hungarian Folktales by Linda Degh,Linda Dégh, Vera Kalm in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. I Don’t Know

AT 532 (I Don’t Know); a complex combination of elements of 314, 510A, 530, and 532, particularly widespread in Central and East Europe. The Hungarian subtype, MNK 532 (Nemtudomka), lists 34 variants, some identified as “Male Cinderella” because of the close parallel with episode III of 510A (Cinderella).

Tape-recorded in 1949 at the home of the narrator. It was one of those cold winter evenings when a few neighbors came over to listen to her tales. It was usually one of her grandchildren who asked for a particular story, and if she was in the right mood for that one, she began to talk, sitting next to the cradle and occasionally rocking the baby with her foot. She learned the story from her godfather, the farmer Mátyás Mátyás, for whom she worked when she was young.” We don’t want to be bored,” he would tell her while she was hacking beets, “I shall tell a story if you listen.” In the course of time, this tale became one of the most popular pieces that she told at wakes, entertaining mourners at the vigil, during which attendance was obligatory from 6 p.m. until the morning bell-ringing. The need for a long story made this extraordinary narrator expand her godfather’s original version and display her unique creativity Six years after Mrs. Ambrus Jordáki’s wake, villagers still recalled Aunt Zsuzsa’s poignant performance on that occasion.

The original was a retelling of the five-page storybook version of folklorist and writer Elek Benedek (1859–1929). Only the title of the booktale—“Timberland Castle”—as I Don’t Know’s ambiguous reference to his residence, remained unchanged.

This was the longest and most elaborate tale I recorded from Mrs. Palkó. Even this lengthy telling cannot be called “complete,” as episodes and motifs were borrowed from other tale types and the threefold repetition of events is not consistent; nevertheless, it is representative of her superb storytelling art. Her performance is characterized by colorful, artful use of language and style; masterful character descriptions; carefully depicted sentences and mental dispositions; elaborate fast-breaking dramatic dialogues and elaborate details constructed through meticulous description of landscapes, environments, and physical conditions. She often stops or slows down the tempo of events to explain and interpret, and prepare her audience for what is forthcoming. For her the tale is not a cool, objective outsider’s account. Deeply committed, she lives in the tale, identifies with her heroes, suffers with them through their ordeals—as if she herself would try to find words of consolation for the steward, as if she would teach I Don’t Know the chores of the kitchen help. Her narration is realistic, mirroring experiences of her personal life, yet she keeps the magic world of the tale intact. Like other expert storytellers, Mrs. Palkó knows that the mingled presence of reality and fantasy is essential to magic tales. In her stories, the actors act according to the tale logic; the flow of events is governed by the marchen’s world view, and style and form utilize the folktale’s vocabulary and inventory of formulas. Mrs. Palkó frequently uses the same words, sayings, and formulas describing identical situations in diverse tales as, for example: “We are not born all at the same time and shall not die at the same time” (also in “The Sky-High Tree” and “The Princess” in this collection, as well as in her untranslated tale, “The Flea Princess”); “when the others eat oats, then he gets hay” (also in “The Sky-High Tree,” below, and “Ej Haj,” untranslated). But her resort to formulaic vocabulary does not make her prose repetitious, or dull; on the contrary, it gives her style a specific rhythm and flavor as documented in her special treatment of the following episodes: 1) the consolation of the widowed king; declaration of war and the king’s departure; the steward’s gradual change of heart; 2) I Don’t Know and the soldiers in the stable; 3) the magic horse instructing I Don’t Know; 4) descriptions of the city, people on the street, the royal family, and the princesses; 5) the portrayal of the cook; 6) the mockery of the brothers-in-law; and 7) description of the splendor and parade as the young couple enter the royal palace.

Once upon a time, beyond seven times seven lands, there lived a king and a queen and they had a beautiful little son. The boy wasn’t more than four. He was four years old. They loved him so dearly that they found all their joy in the child. He was very lovely, with a head of golden locks. They delighted in him but their happiness didn’t last long for the queen fell ill and died. The child became an orphan. Oh, how grief-stricken the king was! He wept bitterly night and day. He couldn’t eat, couldn’t sleep, all he ever did was weep. He just couldn’t control himself. There was a beautiful statue of the queen in the palace. Every single day the king went to kneel before it to pray for her soul but he couldn’t pray for all the weeping and sobbing. He was overcome with tears all the time.

The king had a steward whom he had always considered to be very, very fairminded. The steward visited him every day for he knew that he would always find the king weeping. He went to console him:

“Your Royal Highness, why are you crying so much? Surely you know that we were not all born at the same time and that we cannot die at the same time. So accept the will of God, who let her live this long and has now let her die. Such is the order of things. Your Majesty will wed again, take another wife, and go on living. So why keep crying so much?”

And so he tried to comfort him day after day, but the king just continued grieving for his wife. He would never find a woman as beautiful and as good as his first wife was, he said. Well, one day, when he was once again in tears, crying until his heart nearly broke, the steward came to see him and said:

“Great king, can’t you compose yourself—do you want to destroy yourself too? And who will look after the little boy if he doesn’t even have a father? You may want to die, so deep is your sorrow, but have pity on your small son!”

“Well, if it has to be, it has to be,” he said, “I have to accept my fate for I see that I can’t get her to come back no matter how much I cry, or even if I kill myself.”

“I believe,” said the steward, “that one can’t forget, for he who truly loves his wife has trouble forgetting. Just accept that we don’t come into this world together and we don’t leave it together!”

Well now, the king asked that the steward should come to see him more often to reassure him, for when he was alone he kept remembering his wife and was always weeping. So the steward visited the king more frequently and consoled him so he wouldn’t go on crying forever.

Now then, the boy could have been about six years old. He had grown well and become unusually tall. People might have thought the child was ten, he had grown and developed so beautifully.

One day a courier arrived, bringing a letter, a letter with a seal affixed to it—and handed it to the king. The king accepted it, looked it over and, God Almighty, he found that he was summoned to war. They were warning that the country was about to be invaded by the Tatars. The courier said that the king should muster his troops and if he wanted to save his country, he should confront the enemy. If he didn’t, they would invade and take away his country.

Well, the king wasn’t as sorry for his country or for anything else, as he was for having to take leave of his young son. Most of all he was worried that the boy would have neither a mother nor a father. What would become of the child if he were to lose his life? In those days kings too had to do battle, not like nowadays when only soldiers, officers and noblemen do—the country’s “greats” don’t go to war. Then, to be sure, kings had to take up arms.

For a while the king was in deep thought.

Then he said: “My heart is breaking for my little boy.”

And the steward said: “No, it isn’t, no, it isn’t breaking, why should it? No harm will come to him.”

“To whom can I entrust him? Who would be as good to him as I was,” said the king. “Look, steward, I know you as being the most faithful to me, you were the one who consoled me, so I believe you will not treat the boy badly if I place him in your care.”

“I’ll treat him as if he were my own,” said the steward.

It happened that the steward’s son was as old as the king’s. They were the same age.

“Well, mine is going to school, they can go together. Or, better still,” he said, “I’ll get a tutor to come to the palace to teach him. I’ll not let him go to school. He’ll get a good education while Your Majesty is away. Don’t worry about the boy,” he said, “he’ll not have a bad life here, with me. I’ll treat him like my own, even better.”

“Then,” said the king,” if you keep my son, take good care of him, have a priest and a teacher give him an education so that he will learn and develop and not suffer any want while I am away—then, God willing, upon my return I shall elevate you to a high position. You will be second only to me.”

The king would make him prime minister, if he cared for his child.

“That’s agreed, your Majesty,” said the steward, “the smallest of your worries should be larger than this, for no harm will come to your boy.”

Now then, one day the drums started rolling, the time had come to go to war. They were beating the drums and calling up the soldiers, assembling them. When they were ready to leave, all the horsemen gathered in front of the palace, waiting for the king to lead them. But the king was weeping inconsolably, he just couldn’t, couldn’t part with the boy. He started for the gate, perhaps even ten times, always returning to embrace and hold the child, lamenting that he was unable to leave him. And the steward continued to comfort the king, reassuring him that the boy would have a good life in his household. Finally, after urging the steward once again to be kind to the boy, he was ready to leave. They set forth to the sound of the band playing loudly. And the boy stayed behind. He, too, shed bitter tears for he could now understand that his father had left for the war and God only knew if he would ever return. The steward called the boy pet names, talked to him endearingly, took him to his own mansion which was nearby and brought him over to his son to play, so the child would be cheered. He even let the boy attend school a few times so he could enjoy the company of other children and forget. He was so good to the boy that he couldn’t have been any better to him had he been his own.

About a month had passed when suddenly something evil took hold of the steward’s heart. He said to his wife:

“Wife, wouldn’t it be better if we took less good care of this boy and gave him only the bare essentials? Just enough so he wouldn’t die of hunger. Why should we be so good to him? Maybe, somehow, he will perish and then my son would become king. If the king’s son were to die, my son could succeed to the throne. We needn’t tend to this boy’s comforts so much,” he said, “and, who knows, he may just die.”

Then the wife said: “I don’t mind.”

So they cut down on his meals and food. They gave him less and less every day. They didn’t even let him share what they ate but always gave him something worse. Then they no longer allowed the boy to eat in the room with them—they chased him out into the stables. It is there he had to eat the small slice of dry bread he received. The boy realized the bad turn his life had taken. The servants, too, noticed that the child was always sent out to the stables with only a piece of black bread to eat. They noticed that the steward wanted to put the boy’s life in danger. The soldiers felt sorry for him—there were soldiers working in the stables—and he grew to like them so much that he could hardly do enough to please them. He tried to be near them all the time, watching them work and shovel manure, so he took a pitchfork and helped them. They told him in vain that he was the king’s son, that such work was not for the likes of him, that he needn’t do it.

“Never mind,” he said, “I like to work and to help you. You’ll get done sooner.”

The stable was filled with two rows of horses, horses so fat that they seemed to be bursting. And there was a scrawny colt lying on the floor in a corner. It was so skinny that its legs were dangling criss-crossed and it was too weak to disentangle them. The boy saw it and said to the soldiers:

“Uncle, uncle soldier, what is wrong with this colt, why is it so thin?”

“Well, son,” he said, “it is like that.”

“Why is this colt not eating like the others?”

“Because they are not giving it the same feed as the others.”

“Why aren’t they? Poor thing, it could use something better.”

“Son,” he said, “when the others get oats, this colt gets hay, and when the others get hay, then he gets oats. But we are never allowed to give it the same amount as the others or as much as it would want. Yet it knows how to ask for more. But it is forbidden, once and for all, to feed it the same as the others.”

The boy was saddened. He could see that the colt couldn’t stand up on its legs, it was just lying there. Every time he went to the stable he spent a long time standing by the colt’s side, then by its head, looking at it and feeling sorry for it.

“Oh, poor animal, how scrawny it is,” he said. “I am sorry for it.”

Well, the soldiers got used to having the boy around. They saw how kind he was, how he helped with giving the animals water and with everything else. No sooner did a speck of manure fall on the floor than he rushed over to pick it up. He wanted to make sure that th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Series Editor’s Preface, by Carl Lindahl

- Foreword, by Linda Dégh

- A Note on the Texts

- The Tales of Zsuzsanna Palkó

- 1. I Don’t Know

- 2. Zsuzska and the Devil

- 3. Death with the Yellow Legs

- 4. The Glass Coffin

- 5. The Count and János, the Coachman

- 6. The Princess

- 7. The Serpent Prince

- 8. The Fawn

- 9. Józsi the Fisherman

- 10. The Sky-High Tree

- 11. The Blackmantle

- 12. Prince Sandor and Prince Lajos

- 13. András Kerekes

- 14. The Psalm-Singing Bird

- 15. Peasant Gagyi

- 16. The Golden Egg

- 17. Nine

- 18. The Red-Bellied Serpent

- 19. The Twelve Robbers

- 20. Fairy Ilona

- 21. The Three Archangels

- 22. The Smoking Kalfaktor

- 23. The Turk

- 24. Anna Mónár

- 25. The Wager of the Two Comrades

- 26. The Székely Bride

- 27. The Nagging Wives

- 28. Peti and Boris

- 29. Könyvenke

- 30. The Uncouth Girl

- 31. The Dumb Girl

- 32. The Two Brothers

- 33. The Gypsy King

- 34. Gábor Német

- 35. Margit

- Glossary

- Index of Tale Types and Motifs