1

Introduction

I would not give a fig for the simplicity this side of complexity, but’would give my life for the simplicity on the other side of complexity.

—Oliver Wendell Holmes

Over the last decade it became increasingly clear that the complexities of solving problems at the intersection of people s lives, technology and business would require a holistic interdisciplinary process that gave equal weight to many skill sets and disciplines. Gone are the days that a single person or discipline could possess the skills and experience necessary to design and deliver useful and usable products and services.

—Challis Hodge

Individuals seek information because they realize that their knowledge about a situation is incomplete and that the information they need can be found within the system. Supporting the user’s information needs is the basic requirement of most systems. Thus, most web and paper documents are designed with one of two assumptions:

- They help people who know what they want and who need help accomplishing it, with “it” ranging from buying a new computer to completing a vacation request;

- They help people learn information, such as when a person goes to the web to find details about a medical problem, investing in a company, or learning a new software program.

Designs that address the information needs of the first bullet assume the information requirement is a linear sequence simple tasks. The design can walk users through the process and they go away happy. But this book is not concerned with design for the first bullet; it addresses the problems of supplying information for the second bullet. Sprague (1995) claims that the major value of online information “derives from its ability, to expand the scope of information management from facts in the form of data records and databases, to concepts and ideas that are generally captured, stored, and communicated in the form of documents” (p. 33). Implicit within his claim is the value-add of having information that can address complex situations by providing that information to a user at the time it is required.

Here’s an adaptive interface for cardiac physicians that describes the type of system I envision being developed by the methods of this book.

Physicians need to retrieve rapidly the right patient’s information, whatever the amount and the type, elementary or composite, the modes of presentation and the semantical diversity of their relationships. For example when reviewing an ECG, the user may want to directly retrieve the past history of drugs prescription without need to go back and browse the totality of the patient’s clinical history.

A possible solution is to base the user interfaces on the concept of hyper-media navigation. The latter allows direct access to the relevant data an the adaptation of the data presentation mode and of the screen layout according to the user requirements.

A human/computer interface has to be ergonomic (coherent, concise, reactive, structured and flexible) and customizable to and by the user. It must automatically adjust its look and feel to suit the requirement of individuals or groups of users. User interfaces have to take into account the cognitive characteristics and the psychological behavior of each user. (Ghedira, Maret, Fayn, & Rubel, 2002, p. 219–220.)

In their paper, Ghedira et al. address the problem from a technical approach; a line of research which is making great progress and is essential for implementing usable and functional systems. However, like most adaptive hypertext researchers, they ignore most issues revolving around the content of the system: How should users needs be defined, what are those needs, what information supports those needs, and how should it be presented. Granted, issues about analysis, design, and creation of content are outside the research scope of computer science, while it is squarely at the center of the research scope for information design and technical communication. This book strives to contribute to information design and technical communication by building part of the theoretical foundation needed to develop the content for adaptive systems.

When a person works within a situation that is not as cut and dry as something such as completing a vacation request, their information needs fall in the latter bullet. The users have real-world information needs; they want help directly relevant to solving their needs to address real-world issues that often involve high-level reasoning and open-ended information needs. In other words, it is hard to clearly define exactly what information is needed and when enough has been gathered. The users face a complex situation that require answers to open-ended questions and any linear information presentation sequence breaks down. Forcing a linear sequence onto these situation creates major usability problems with the resultant system. Conklin (2003) referred to these as “wicked problem,” contrasting them with tame problems which have straightforward and clearly defined solutions.

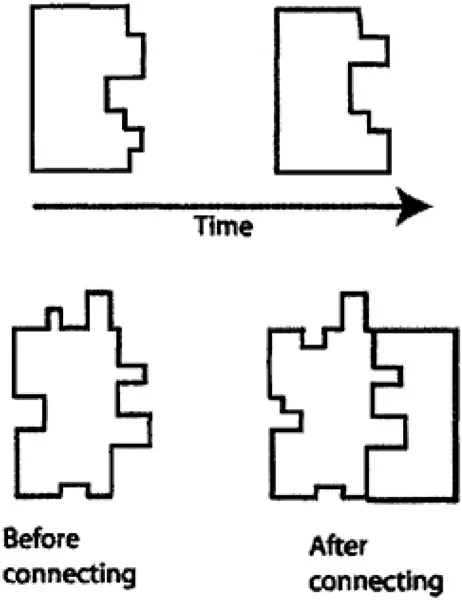

If the need for information were a jigsaw puzzle, in a straightforward problem, the person can work with the information in the same way a normal jigsaw puzzle is solved. Each piece is static and never changes. Matching pieces are found and attached. If they happen to fit into a place in the puzzle that is not yet assembled, then two or three connected pieces can be placed aside and inserted later. But in a complex situation, the pieces are not static. Imagine working on a jigsaw puzzle (Figure 1.1) where the pieces laying on the table change over time and fitting two pieces together changes how the other sides of each piece fit into the puzzle. Yet in a complex situation, the user’s goals and information needs tend to conform more closely to this latter view than the former static jigsaw puzzle.

Just like the dynamic jigsaw puzzle, real world work is complex and is based on a collection of different systems that interact in complex ways; ways so complex that basically nobody understands the entire system (Beyer & Holtzblatt, 1998). Realistically, the entire sequence can’t even be completely defined because of both the difficulties of defining the minute details that make it up and human nature that leads people to jump around within the data. Users come to multiple decision points, and the sequence starts to form a complex web. Allen (1996) considers how people each look at problems differently.

An individual facing one kind of problem may need to explore a topic area in a different way than an individual facing a different kind of problem. This kind of problem-based flexibility in the presentation of information is not frequently found in current information systems. In part, this inflexibility may be attributed to the data-centered approach, which focuses on the data rather than on the uses to which the data can be applied, It is also true that implementing information systems that can tailor their functioning to the different problem faced by users is far more difficult than implementing systems with less flexibility, (p. 115)

Fig. 1.1. Working a dynamic jigsaw puzzle. The pieces are not static, instead they change both over time and from being fitted together.

Handling the shift from a linear information model to the ill-structured model requires a design shift. Redish (1990) argues that documentation move up a level and address goals and task repertoires and she recognizes that that emphasis on “higher than discrete task” is crucial for anyone doing everyday work. Accomplishing this requires us to view the creation and presentation of content and its subsequent communication from a humanistic viewpoint, rather than a mechanistic one (Whitburn, 1984). The user goals and information needs must be placed within a proper social and technical contexts and designed to assist people, rather than doing it for them (Belkin, 1980; Ruskin, 2000; Schriver, 1996). The driving force for this shift arises because people, rather than machines, are reading the information. Modern web interfaces frequently deal with the presentation of vast quantities of information, and often address complex situations. To complicate the situation, the basic information must meet diverse needs. Unfortunately, how well the interfaces addresses the user’s complex needs, rather providing individual information elements, varies greatly between systems.

Document management or content management systems are one of the current rages in the trade literature. The vendors promise their system can capture all the documents within a company and produce it at will. However, the reality tends to be much more muted. For example, Rein et al. (1997) point out that most of the successful document management applications are relatively simple, well understood work processes (phone directory, library catalogs). On the other hand, large repositories with varied information organization and lack of strict control tend to provide less than hoped for returns. The traditional document management model tries to identify and retrieve a small number of documents out of a much larger collection. With simple situations, a single query usually suffices. In contrast, as the situation becomes increasingly complex, the fundamental goals becomes one of seeking out and learning about information to understand the relationships within clusters of similar documents, and exploit those relationships. Rather than a single query, decision making requires integrating the results of multiple queries (Ebert et al., 1997). The question as shifted from a simple “does this exist” to a much more complex formulations such as “I need to analyze these documents to understand about X. They all discuss X, but which ones contain relevant information? And, more importantly, what is the relevant information for my specific needs right now?”

Single sourcing needs some level of content management system running in the background to control the material. Books such as Rockley, Kostur, and Manning’s Managing Enterprise Content: A Unified Content Strategy (2002) provide high quality information on making use of those systems. This book strives to extend their position to address creating dynamic information systems. Rather than considering how to use a single sourcing systems to create multiple static documents (e.g., print, online help, training), this book looks to move past that view to one of generating documentation customized to each reader’s needs. The text presented to a reader conforms to her knowledge level and reading ability so it can best communicate the content.

Web-based information systems are the current best method of creating a useful package of knowledge and delivering it to the people that need the information. Complex situations requiring complex information presentation are a way of life in the modern world. Part of the frustration many people feel searching for information in a computer system arises because the required information they need is hard to integrate into a coherent whole. Terveen, Slefridge, and Long’s (1995) work revealed that:

The pragmatics of knowledge use are critical. Simply recording a factor is not enough; issues such as where in the process knowledge is to be accessed, how to access relevant knowledge from a large information space, and how to allow for change also must be addressed, (p. 3)

Likewise, Mirel’s studies have found users have different conceptions of how to accomplish a task. “In actual work settings, users define their own tasks and task needs according to situational demands, not program design” (Mirel, 1992, p. 15). The design of those systems must encompass a total system that revolves around the goals and information needs of a human and supplies information that makes sense within the person’s real-world situation. Castel (2002) aptly summed up my argument when he said, “Computing does not merely process information, it commits to a certain representation of information” (p. 30). In this book, I am concerned with designing to improve human performance within specific situations through the interactions between human and computer. In contrast to many existing systems, the complex information systems I envision and describe in this book require the system to efficiently supply information on demand and dynamically adjust that information to maintain the proper detail level.

It is important to understand this book does not consider issues such as natural language generation or other methods of having a computer system generate the information from essentially the ground up. Whereas research continues on those systems, they are a long way from being commercially viable. Instead, the information needs must be meet by creating a proper set of templates and having technical communicators create the content and metadata describing that content.

The examples listed in the sidebar highlight the disconnect between what the person really wants to accomplish and the information the system provides. In each example, the information could exist within the system, but it didn’t allow for easy manipulation and integration. Interestingly, when people analyze situations, they enviably must manipulate and integrate information, while they interact with a systhat presents it in a limited number of ways (often only one). Cypher (1986) nicely sums up the fundamental problem plaguing current design efforts.

Program designers put a great deal of effort into allowing users to perform single activities well, but considerably less effort goes into allowing users to arrange those activities, (p. 244)

I interpret “allowing users to arrange those activities” to mean providing information useful to address open-ended problems and complex situations which require high-level reasoning. Quality design analysis should not provide only a list of topics describing the data but should also address the real-world situations, goals, and information needs of the users in the appropriate context. Understanding of a complex situation comes from understanding the relationships between multiple pieces of information, then the design must support revealing those relationships. In other worlds, we need better ways to integrate and communicate the information to a user.

Complex open-ended information needs

Replacing parts on a car. This one appears deceptively simple. Provide the steps for replacing the part, what more can the user want Actually, users needs should be addresses more carefully. Ignoring the professional mechanic, consider how a skilled weekend mechanic and a person with basic car knowledge need different levels of presentation and step detail. Consider all t...