eBook - ePub

Solving Behavior Problems in Math Class

Academic, Learning, Social, and Emotional Empowerment, Grades K-12

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Solving Behavior Problems in Math Class

Academic, Learning, Social, and Emotional Empowerment, Grades K-12

About this book

Reduce the number of discipline issues that arise in your math classroom with ideas from math education expert Jennifer Taylor-Cox. In this book, you'll learn a variety of ways to handle disruptive, disinterested, avoidant, and/or disrespectful students in K-12 math classrooms.Using realistic, case-by-case examples, the author reveals practical strategies for eliminating teacher-student tensions related to power struggles, bullying, disengagement, and more.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Solving Behavior Problems in Math Class by Jennifer Taylor-Cox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Past

The art of teaching is complex. We have so many distractions in our classrooms. Some students come to us with enormous baggage that impedes the teaching-learning process. Behavior problems relate to classroom discipline. Discipline should not be viewed as an ugly word. Discipline comes from the word disciple. Discipline means teaching. The goal is to educate, and there are effective strategies that can and should be used to improve the instructional environment. We need to ask: Which strategies work? What do they accomplish? How and why do these strategies work? Which strategies do not work? Why are they not working? We need to implement classroom discipline based on the answers to these and other questions.

In my doctoral studies, I learned that there are literally thousands of “research” pieces on the topic of classroom discipline and parts of this chapter are taken directly from my literature review. Amidst the mixture of information of yore and present-day streams of inquiry, we find opinions, commentaries, prescriptions, tentative assumptions, redundancy, contradictions, testimonies, and rationales. Two major themes emerge: Theories of Blame and Theories of Remedy.

Theories of Blame

This conglomeration of literature offers reasons why students “misbehave” in class and typically attaches accusation, sometimes, even condemnation. Embedded within this mass of literature are six subcategories asserting diverse sources of deficiency and implied causality. These include (1) Students are to blame because they have inherent intentions that become classroom behavior problems; (2) Parents are to blame for student misbehavior because of faulty child-rearing practices; (3) Biochemical conditions are to blame because some students have medical reasons that explain the misbehavior; (4) Peer influence is to blame because of peer pressure and the desire some misbehaving students have to perform for their peers; (5) Educators are to blame for problematic classroom behavior because they lack expertise and/or have erroneous expectations; and (6) The curriculum is to blame because it does not meet the academic needs of the misbehaving student.

Should We Blame the Students? Some Say, “Yes.”

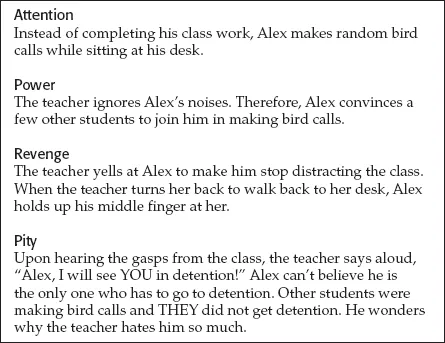

Alfred Adler, whom I refer to as the grandfather of discipline research, offered us a framework for the study of classroom discipline. The goals of misbehavior that Adler (1930, 1938) identified, Dreikurs (1948, 1958, 1972) later refined, and many classroom discipline resources still use today, offer teachers the reasons that children misbehave. According to the Adler-Dreikurs model, students have problems behaving appropriately because they successively seek attention, power, revenge, and pity (Dreikurs, 1972).

The following scenario is an example of a student moving through the complete Adler-Dreikurs model. See Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1

Unfortunately, this type of situation plays out in many classrooms. Some students seek these goals of misbehavior. Other students do not successively move through all of the goals. Still other students misbehave for different reasons.

Yet, simply blaming the students does little to solve behavior problems in math class.

Should We Blame the Parents? Some Say, “Yes.”

Among the arrays of information that children absorb are the interactions of social beings in a particular setting, usually the home. They learn, at very young ages, how to gather attention, display needs and desires, and interact with or gain reaction from adults. Parents, a child's first teachers, respond to needs, desires, and curiosity in various ways. Children who exhibit intense behavior problems in school often come from homes characterized as highly stressful and live with adults who have difficult temperaments and/or who lack adequate parenting skills (Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992). Bearing in mind that students spend the majority of their lives out of school, it is important to consider home environments, specifically parents (or those acting as parents), as potential influences and possible sources of student behavior problems, keeping in mind that some students who misbehave come from stable home environments with supportive parents.

Households that are characterized by high levels of aggression, malice, oppression, and vitriol are likely to produce children with dispositions that engage in these behaviors. The lines of the famous poem by Dorothy Law Nolte (1998) summarize the point: “If a child lives with criticism, he learns to condemn. If a child lives with hostility, he learns to fight.”

Yet, simply blaming the parents does little to solve behavior problems in math class.

Should We Blame the Biochemical Conditions? Some Say, “Yes.”

Biological factors may also help explain the behavior of children. While we have advanced beyond the testing and measuring of children's skulls to research biologically connected behavioral problems in children, many educational practitioners and researchers continue to turn to the field of medicine for answers to classroom behavior problems. Terms such as “defective students” and “maladjusted children” have been replaced by labels such as “emotionally disturbed,” “socially impaired,” and “behaviorally disabled.” These new labels are often connected to medically diagnosed conditions such as ADD (attention deficit disorder), ADHD (attention deficit with hyperactivity disorder), and conduct disorder.

Compounding the issue of biochemically explained behavior is the fact that some students come to school medically undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. Many children have inhabited several classrooms prior to official, medical diagnosis of behavior-related conditions. Therefore, it is possible that in any given classroom there are a few students who may have a medical explanation for inappropriate behavior but have not yet received official diagnoses that identify a primary cause.

Yet, simply blaming biochemical conditions does little to solve behavior problems in math class.

Should We Blame the Peers? Some Say, “Yes.”

Some students learn how to behave by observing their peers. The desire to be like others, particularly those marked “favorite” or otherwise socially promoted, is an intense force often referred to as peer pressure. “Our peer group is a relentless influence on our behaviors, regardless of age or societal role” (Kauffman, Mostert, Trent, & Hallahan, 1998, p. 96). Considering that students are continually reforming their own self perceptions through the eyes of others, it is not surprising that many students feel obligated to follow the often wayward directions of peers rather than adults.

Numerous classroom behavior problems can be described as peer performances. As the sideshows of disruption are reinforced by peer acceptance and oft times urged on by peer pressure, the classroom environment becomes one composed of copious, yet traceable problems with student behavior.

Yet, simply blaming the peers does little to solve behavior problems in math class.

Should We Blame the Educators? Some Say, “Yes.”

Just as students vary in skill level, personality, and behavioral tendencies, school personnel do as well. Some teachers and administrators are particularly skilled educators and leaders, others are mediocre, and still others are less than adequate. These variations in educator expertise have been connected to classroom behavior problems.

Violent Schools—Safe Schools, a report to the National Institute of Education, revealed that there were higher rates of suspension in schools that employed teachers who had low expectations of students, demonstrated racial bias, and generally acted disinterested in students (Wu, 1980). In settings such as these, a self-fulfilling prophecy is likely to occur. The teacher expects some (or all) students to perform poorly in academics and to exhibit behaviors of misconduct. Consequently, the students conform to teacher expectations. As the Stephen Covey adage goes, Argue for a weakness and it's yours! (Covey, 1990). Teachers who anticipate and focus on negative teacher/student interactions and problems with classroom behavior are prone to participate in the like.

Yet, simply blaming the educators does little to solve behavior problems in math class.

Should We Blame the Curriculum? Some Say, “Yes.”

Other in-school factors such as curricular decisions have been shown to have an effect on classroom behavior. Often students display misbehaviors when the curriculum has not adequately met individual needs. Perhaps the task given to the student is too easy, or too difficult. If the work is too easy, students may act up because they are bored. If the work is too difficult, students may act up because they are frustrated.

Yet, simply blaming the curriculum does little to solve behavior problems in math class.

Theories of Blame: An Eclectic Justification, a Tool, or a Conundrum?

The abundance of theories that attach blame and causality to student misbehavior offer educators, students, and the larger society explanations for student behavior problems in the classroom. The explanations, although not comprehensive or applicable to all students, often pave the way for excuses for educators not to address the complex problems of student misbehavior.

♦ If the problem resides at home, how can the school address the issue?

♦ If the child has a medical explanation for misbehavior, how can the classroom teacher change his behavior?

♦ Are some of the blame theories, however accurate or inaccurate they may be, used to justify and perpetuate the problems of student misbehavior in the classroom?

Herein lies the zenith of the conundrum; educators can serve as both culprits and victims of student misbehavior in the classroom. Instead of focusing on blame, we need solutions.

Theories of Remedy

The literature on classroom behavior and discipline packaged in numerous classroom discipline “remedies” is a conglomeration of theoretical reflections and prescriptive notations. These various programs can be clustered into three major categories. The first major classification involves theories and techniques associated with behavior modification. The second category is concerned with authoritarian rule in the classroom. The third classification encompasses communicative and community environments in the classroom.

Behavior Modification

The majority of classroom behavior programs address behaviorism theory and behavior modification techniques (Kohn, 1996; Slee, 1995). Dating back to the work of Edward Thorndike (1913), scientists have turned to the animal kingdom to find answers related to the behavioral tendencies of human beings. Although B. F. Skinner (1953) is typically credited for “operant conditioning,” which is the basic premise behind behavior modification, it was Thorndike (1913) who conducted the ground work (Woolfolk & McCune-Nicolich, 1984). Thorndike's animals of choice were cats. Using boxes with removable bolts on the lids, he contained the cats until they could figure out how to dislodge the bolts to obtain freedom and food. Over time, the cats “learned” to quickly escape and were thus rewarded with food. Thorndike concluded that “any act that produces a satisfying effect will tend to be repeated in that situation” (Woolfolk & McCune-Nicolich, 1984).

Skinner (1953) pushed Thorndike's theory to the next level, which moved beyond basic “stimulus and response” to the deliberate choice of action (operant) and associated consequences. Using rats and pigeons to test his theory, Skinner created cages with small food dispensing devices. The subjects were conditioned to dispense the food (the rats pushed a bar and the pigeons pecked a disk). Skinner studied the effects of various consequences (e.g., no food dispensed, electric shock) on behavior. Using these and similar “scientific” experiments, educational psychologists established a framework for the study of human behavior, that is, behaviorism, also known as behavior modification.

Behaviorism is typically understood through an action (behavior or response) situated between two mediums. Something precedes the action and something follows the action. In light of the theory of operant conditioning, the provoking medium is referred to as the “antecedent” and the resulting medium is designated the “consequence” (Woolfolk & McCune-Nicolich, 1984). In the study of operant behavior, specific actions result in specific outcomes.

Typically, approaches to behavior modification focus on the consequences or operants associated with the behaviors of children. Educators are supplied with a host of possible consequences to link with student behavior in an attempt to change the behavior to what is desired by the teacher. These are the “bags of tricks” that have replaced the paddle and dunce caps of old (Dubelle, 1995). The range of possible teacher-dictated consequences falls under the specific prototypes of positive reinforcement (which includes rewards), negative reinforcement (which, contrary to public perception, does not include punishment), extinction, and punishment. Positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement are typically used to increase specific classroom behaviors, while punishment and extinction are usually employed to reduce specific classroom behaviors (Kauffman et al., 1998).

Reinforcement—increasing specific behaviors

Reinforcement is the method of using a repeated consequence to increase the regularity of a specific behavior. According to behavioral psychologists, a reinforcer is required to increase the frequency of an appropriate behavior. Likewise, if a student or students repeatedly display a specific misbehavior, then some type of reinforcement is perpetuating that behavior (Woolfolk & McCune-Nicolich, 1985). Included in the reinforcement construct is the notion of consistency. Most discipline program packages make mention of consistency in teacher reaction or interaction to eliminate behavior problems and promote positive classroom climates. Because reinforcement involves frequency, consistency is a mandatory factor that has the potential to strengthen or negate teacher-established consequences.

Positive reinforcement is the presentation of a stimulus immediately following a specifc behavior. The range of positive reinforcement possibilities used by teachers is nearly infinite. Educators tend to assume that stickers, praise, credit, smiley faces, A's, candy, free-play time, pats on the back, winks, and thumbs up signals serve to promote positive behavior in classrooms. The fallacy is that, according to the behavioral scientists, nothing is a positive reinforcer until it serves to reinforce a behavior. Therefore, one cannot be sure that a reward is a positive reinforcer until it actually produces the desired behavioral outcome. Moreover, the behavioral scientists assert that reinforcers only work i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 The Past

- 2 A New Perspective—Empowering Students

- 3 Kindergarten through Fifth Grade Math Students and Situations

- 4 Middle School and High School Students and Situations

- 5 Smart Moves

- References