![]()

Part I

Climate change and Economic Policy Instruments

![]()

1 Climate change and the Power Industry

Two islands have recently disappeared under the waves of the South Pacific Ocean. Tebua Tarawa and Abanuea, of the tiny island state Kiribati, have been flooded by rising sea levels. Neither of these two islands was inhabited, but many more are threatened, including the remaining thirty-three islands of Kiribati. Continuing sea-level rise could threaten the survival of thousands of islands whose highest points are often not more than a few metres above sea level, as well as other low-lying areas – among them many with substantial animal and human populations.

As a result of growing fears for the climate, negotiations for a global fight against climate change started in the late 1980s. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC) was negotiated at the ‘Earth Summit’ in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 and entered into force in 1994. However, the commitments made under the FCCC proved inadequate and negotiations began to strengthen them. These efforts resulted in the adoption, at the Third Conference of the Parties to the FCCC (COP-3) in Japan in December 1997, of the Kyoto Protocol. This protocol sets out legally binding quantified emission limitation and reduction commitments (QELRCs) for the industrialized countries. The overall target amounts to a 5.2% reduction in emissions from 1990 levels, for a basket of greenhouse gases, by the commitment period 2008–12. But agreement on the details of implementation proved elusive, and at COP-6, in November 2000, the international negotiations collapsed. The resumed COP-6, meeting again in the summer of 2001, finally achieved the desired outcome on the outstanding issues in the form known as the ‘Bonn Agreement’. However, the process now has to move on without the participation of the United States, withdrawn from the protocol at the beginning of 2001 by the newly elected President George W. Bush.

In the industrialized countries, the power sector emits roughly one-third of GHG emissions, mostly from burning fossil fuels in large-scale power stations. This makes the sector both large and relatively easy to regulate, and consequently the prime vehicle for industrialized countries’ governments in their efforts to achieve the target set at Kyoto.

However, the ongoing process of liberalization throughout the industrialized countries reduces the possibilities for ‘easy’ regulation of the power sector. Liberalization is pursued for many reasons, including increasing industrial competitiveness through lower energy prices. Cost reductions by the power sector and lower prices for consumers could lead to increased demand and emissions.

This book, Climate Change and Power, will focus on the interaction of these two highly dynamic fields: first, the international process to combat climate change, considered to be the greatest environmental challenge facing the world, which started only a decade ago but has already eclipsed many other environmental treaties; and second, the policies geared towards liberalizing the European electricity sector, started in 1989 in the UK and kick-started for the rest of Europe with the 1996 EU electricity directive. Developments in both these fields progress very quickly, and no doubt by the time of publication the international negotiations on the Kyoto Protocol will have moved on from the Bonn Agreement, and electricity markets will have opened up further than anticipated.

1.1 Climate Change

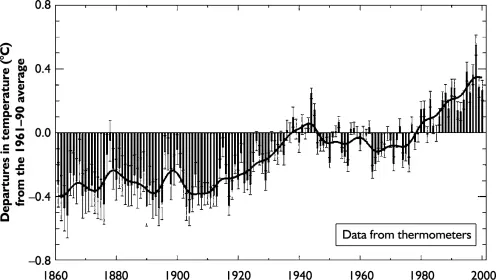

A continuous stream of temperature records was set in the 1990s, making it by far the warmest decade on record. The El Niño year of 1998 was the warmest on record, each of the first eight months a record-breaker in its own right. The year after El Niño, La Niña, is supposed to be relatively cold; but in fact 1999 was the fifth warmest year on record. Looking at Figure 1.1, a warming trend seems hard to deny; and this trend was confirmed again with new temperature records in 2000 and 2001, the latter being recorded as the second warmest year in 140 years.

In 1995 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its Second Assessment Report concluded that ‘the balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate’, and it predicted temperature increases of 1–3 degrees Celsius (°C) by 2100. The Third Assessment Report, finalized in 2001, was much more forceful in its language, stating that ‘there is new and stronger evidence that most of the warming observed over the last 50 years is attributable to human activities’. This report also predicts a much stronger temperature increase of between 1.4 and 5.8°C, nearly double the 1995 forecast. Research by the National Center for Atmospheric Research in the United States also concluded that it is humans, and not natural events of some kind like volcano eruptions or sunspot activity, that are responsible for global warming. Sir John Houghton of the Hadley Centre, chairman of the IPCC, claimed that there was now ‘virtual unanimity’ among scientists that warming was taking place.

Figure 1.1: Variations of the earth’s surface temperature over the last 140 years

Source: IPCC, Third Assessment Report. Climate Change 2001, Working Group I: The Scientific Basis, Summary for Policymakers.

Floods in Bangladesh, floods around the Yangtze river in China, forest fires in Russia and hurricane Mitch, to name but a few of the worst climate disasters in 1998, caused record economic losses totalling $138bn. Hurricane Mitch brought disaster in Central America during the COP-4 negotiations in Buenos Aires in November 1998; the conference passed a resolution in which it ‘expresse[d] to the people and governments of Central America its strongest solidarity in the tragic circumstances they are facing, which demonstrate the need to take action to prevent and mitigate the effects of climate change’. The ever-increasing costs of weather related losses have grabbed the attention of insurance companies, which are now committed participants in the climate change debate. La Niña, in 1999, brought similar disasters, with Cyclone Eline hitting Mozambique and Madagascar. Even the ‘quiet’ year of 2000 saw a series of floods in the UK and mainland Europe, causing great disruption and financial loss. The floods in Britain took place just before the failed COP-6 in The Hague, where Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott, blaming climate change for the inundation, reminded his fellow negotiators of the seriousness of the problem and the urgency of starting to reduce emissions.

The use of energy from fossil fuels and land clearance are the main causes of anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide. These economic activities are therefore the main causes of human-induced climate change; they are also at the very basis of much of our economic life. Thus, to reduce emissions in order to mitigate climate change ‘the world community is confronted with a radical challenge of a totally new kind’; meeting it will not necessarily reduce our wealth but will certainly change our ways.

Under the 1992 FCCC, parties to the convention committed themselves to stabilize GHG concentrations ‘at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system’. The headline commitment for the countries listed in Annex I of the convention, the industrialized countries, was to return GHG emissions to 1990 levels, and to show a reversal in the trend (of growing emissions) before the year 2000. Against the odds, for Annex I as a whole this objective was met, though mainly as a result of the economic transition in eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union rather than of measures taken by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. Indeed, emissions from the OECD are nearly 9% above their 1990 levels in 1998, according to International Energy Agency (IEA) statistics.

In 1995 the parties agreed that these commitments were inadequate and they began ‘a process to enable it to take appropriate action for the period beyond 2000, including the strengthening of the commitments of Annex I Parties’. Specifically, it was decided to ‘set quantified emission limitation and reduction objectives within specified timeframes’. The negotiating process based upon this ‘Berlin Mandate’ culminated at COP-3 in Kyoto, Japan, in December 1997.

The Kyoto Protocol calls for actual reductions of emissions by the industrialized countries of Annex B. These commitments add up to a 5.2% reduction from 1990 levels by 2008–12, calculated for a basket of GHGs, including carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), some industrial gases (HFCs, PFCs, SF6), and emissions and removals arising from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF or ‘sinks’). Table 1.1 sets out the specific targets for each country or group of countries for the first commitment period (2008–12); the Kyoto Protocol calls for rolling commitments, with stricter targets after 2012.

The Kyoto Protocol is a landmark in international environmental policy for its complexity and inclusiveness, having about 180 countries on board. However, Kyoto was the beginning of the process rather than the end point, and negotiations are still continuing to fill the gaps left in the original protocol. From 2 to 14 November 1998 the conference of the parties met again to follow up on Kyoto in its fourth session (COP-4) in Buenos Aires. COP-4 resulted in the Buenos Aires Plan of Action, setting up a whole new round of negotiations. Further details were discussed at COP-5, in Bonn in 1999; a conference that did not generate headline-grabbing news. The Buenos Aires Plan of Action aimed to resolve the outstanding issues of the Kyoto Protocol by the end of 2000, at the sixth conference of the parties. With time pressing on, an extra negotiating session in Lyon and weeks of informal negotiations were added. However, COP-6, in November 2000, in The Hague, failed to reach agreement, even after extra days and nights of negotiations; and it fell to the resumed session of the conference, COP-6bis, in July 2001, to reach the ‘Bonn Agreement’, fulfilling the Buenos Aires agenda.

Table 1.1: The Kyoto Protocol targets

Party | Quantified emission limitation or reduction commitment (% of base year or period) |

|

European Union | 92a |

United States | 93 |

Japan, Canada | 94 |

Australia | 108 |

Other OECD countries | 92–110 |

Russia, Ukraine | 100 |

Other EITs | 92–95 |

a The targets for the individual EU member states are differentiated within the EU Bubble; see Table 2.1.

Source: The Kyoto Protocol.

The main greenhouse gas, CO2, is released during the use of fossil fuels, which supply most of the industrialized countries’ energy needs. A protocol to limit these emissions, and thus the use of fossil fuels, would therefore also limit the potential for economic growth. Some early studies suggested substantial losses of gross domestic product (GDP) if limitations on GHG emissions were imposed. Most recent studies, by contrast, show only small costs, ‘equivalent to forgoing a few months of GDP growth’, losses which are ‘hardly discernible compared with the projected overall growth and uncertainties [in GDP]’. However, as a result of the high-cost perception the protocol includes various flexible mechanisms as the most cost-effective way of limiting emissions; these elements of Kyoto will discussed in more depth in Chapter 2.

Some studies and some recent experience show that large reductions in emissions can be achieved through efficiency measures that were simply overlooked previously. It is possible to look at emissions reduction obligations not as added costs, but as business opportunities. Emissions are waste, and waste means inefficiency and thus excess costs; measures to reduce emissions could reduce waste, and therefore costs. There are also great side-benefits from emissions reduction measures, such as reduced local air pollution – which causes 24,000 premature deaths in the UK alone – and reduced congestion.

1.2 The Electricity Sector

The electricity sector is one of the main sources of CO2 emissions, accounting for around one-third of all such emissions in the OECD. Figure 1.2 displays the sectoral breakdown of emissions, and shows that the energy sector’s contribution is larger than that of any other sector, at 32%. The energy sector as a whole also causes substantial emissions of methane. In 1990 fuel methane emissions together accounted for about 5% of the total GHG emissions in Annex I parties. Many of these countries, therefore, will turn to the power sector for measures to deliver a substantial part of their Kyoto commitments.

The share of electricity in final energy demand has been rising fast, and is projected to rise further in the future. The IEA projects faster increases in electricity use than in any other energy use, with an annual growth rate of 2.9% globally between 1997 and 2010. This analysis shows a strong linear dependence of electri...