CHAPTER 1: Probability and Chance

Probability is …the philosophical success story of the first half of the twentieth century.

—Hacking (1990, p. 4)

Strictly speaking it may even be said that nearly all our knowledge is problematical; and in the small number of things which we are able to know with certainty, even in the mathematical sciences themselves, the principal means for ascertaining truth—induction and analogy—are based on probabilities.

—Laplace (1814/1951, p. 1)

Subjective probabilities are required for reasoning … a theory of partially ordered subjective probabilities is a necessary ingredient of rationality.

—Good (1983, p. 95)

BEGINNINGS

The use of chance devices and the drawing of lots for purposes of sortilege and divination were common to many cultures of antiquity. Classical Greek literature contains numerous references to games of chance at least as early as the Trojan wars, and there is evidence to suggest that such games were known in Egypt and elsewhere long before then. One of the earliest known written documents about the use of chance devices in gaming is in the Vedic poems of the Rgveda Samhita. “Written in Sanskrit circa 1000 B.C., this poem or song, called the ‘Lament of the Gambler,’ is a monologue by a gambler whose gambling obsession has destroyed his happy household and driven away his devoted wife” (Bennett, 1998, p. 34). Gambling had become a sufficiently common form of recreation in Europe by the time of the Roman Empire that laws forbidding it were passed—and largely ignored. The emperor Caesar Augustus (63 B.C.-14 A.D.) was an avid roller of the bones. The bones, in this context, were probably astragali, a form of dice made from the heel bones of running animals. The astragalus, sometimes referred to as a talus, huckle—bone, or knuckle—bone, was shaped in such a way that, when tossed, it could come to rest with any of four sides facing up, the other two sides being somewhat rounded. It is known to have been used in the playing of board games at least as early as 3500 B.C.Dice, which presumably are evolutionary descendants of astragali, are known to have existed in the Middle East as early as the third millennium B.C. According to Bennett (1998), the earliest known six-sided die was made of baked clay around 2750 B.C. and was found in what was once Mesopotamia and is now Northern Iraq.

In view of the fact that chance devices have been used for a variety of purposes for so long, scholars have found it difficult to explain why quantitative theories of randomness and probability were not developed until relatively recent times. Although why a theory of probability was so long in coming remains unknown, there has been much speculation as to what some of the contributing factors may have been. Hypothesized deterrents include pervasive belief in determinism, lack of opportunity to observe equiprobable sets (astragali did not turn up all four faces with equal relative frequency), absence of economic incentives, and lack of a notational system suitable for representing the critical ideas and computations. Each of these explanations has been challenged, if not discredited to one or another degree (Hacking, 1975). There appear what Gigerenzer et al. (1989) refer to as suggestive fragments of probabilistic thinking in classical and medieval literature, and there may have been some theoretical ideas about probability, especially in India, that are lost to us, but apparently nothing approaching a systematic theoretical treatment of the subject was attempted in Europe until the 17th century.

Gigerenzer et al. (1989) attribute considerable significance to the Reformation and Counter—Reformation and the associated clashes between extremist views on faith and reason, which influenced attitudes regarding how beliefs should be justified: |

Confronted with a choice between fideist dogmatism on the one hand and the most corrosive skepticism on the other, an increasing number of seventeenth-century writers attempted to carve out an intermediate position that abandoned all hope of certainty except in mathematics and perhaps metaphysics, and yet still insisted that men could attain probable knowledge.... The new criterion for rational belief was no longer a watertight demonstration, but rather that degree of conviction sufficient to impel a prudent man of affairs to action. For reasonable men that conviction in turn rested upon a combined reckoning of hazard and prospect of gain, i.e. upon expectation, (p. 5)

They continue:

Mathematicians seeking to quantify the legal sense of expectations inevitably became involved in quantifying the new rationality as well. So began an alliance between mathematical probability theory and standards of rationality that stamped the classical interpretation as a ‘reasonable calculus’; as a mathematical codification of the intuitive principles underlying the belief and practice of reasonable men. (p. 6)

Interest in probability was spurred by questions relating to games of chance, such as why the tossing of three dice turned a total of 10 more frequently than a total of 9. Much of the early thinking about the topic was prompted by the specific question of how to divide fairly the stakes in a prematurely terminated game of chance. The following problem appeared in Fra Luca Paccioli's Summa de Arithmetic, Geometria et Proportionality (The Whole of Arithmetic, Geometry and Proportionality), published in 1494: “A and B are playing a fair game of balla. They agree to continue until one has won six rounds. The game actually stops when A has won five and B three. How should the stakes be divided?” (David, 1962, p. 37).

One solution by Paccioli was published in De Divina Proportione (On Divine Proportion) in 1509, and another by Gio Francesco Peverone in Due Brevi e Facile Trattati: Il Primo d'Arithmetica, l'Altro di Geometria (Two Short and Easy Treatises: The First on Arithmetic, the Other on Geometry) in 1558 (David, 1962). These early efforts considered the question of what would be a fair division in specific cases and did not attempt a general solution to the problem. The answers proposed for the cases considered differ from the answers that would be given to the same questions on the basis of probability theory as it now exists, employing, as they did, the notion of dividing the stakes in the same ratio as that of the games won, or a close derivative of it. It is doubtful whether either Paccioli or Peverone had a clear concept of probability. This type of problem appears repeatedly in the writings of 16th- and 17th-century mathematicians and differences of opinion as to the correct answer prompted heated debate (P.L.Bernstein, 1996; Todhunter, 1865/2001).

A significant early contributor to a theory of probability, as we know it—or to a theory of chance, as it was and is sometimes called—was Girolamo Cardano, who wrote a book with the title Liber de Ludo Aleae (The Book of Games of Chance). Although written, according to his own account, in 1525, it was not published until 1663. David (1962) credits Cardano with being the first mathematician to calculate a theoretical probability correctly. Galileo also wrote briefly about the numbers of ways different sums can be obtained with the tossing of three dice.

The Pascal—Fermat Correspondence

Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat thought collaboratively about the stakes—division problem as a consequence of the question being put to Pascal by a gambler, Chevaleau de Méré. Pascal and Fermat exchanged letters on the topic over several months during the summer and fall of 1654. (The collaborators never met before, during, or after their remarkable correspondence.) The correspondence between Pascal and Fermat regarding the stake—division problem is worth considering in some detail, because it is viewed as one of the defining events in the emergence of probability theory as a mathematical discipline. And it provides a glimpse at the kind of struggle that the founders of probability theory had in trying to understand their own intuitions and to make them explicit and clear. An English translation of what is preserved of the correspondence—apparently the surviving record is not entirely complete—may be found in David (1962, Appendix 4).

The specific situation that Pascal and Fermat considered was this. Two players are involved in a series of games and play is terminated when one of the players, say A, is two games short of winning the series and the other player, say B, is three games short of doing so. How should the stakes be divided between the players at this point? The tacit assumption is that A should get a larger share than B because A would have been more likely to win the series had play continued, but exactly what proportion of the total should each player receive?

Fermat had proposed a way of analyzing the situation. In a letter dated Monday, August 24, 1654, Pascal repeats Fermat's analysis and argues that it works for two players but will not do so if more than two are involved. Fermat's analysis starts with a determination of the maximum number of additional games that would have to be played to decide the winner of the series. In this case, the number is four, because in the playing of four games either A will win two or B will win three. Fermat's method then calls for identifying all possible outcomes of four games, of which there are 16, determining the percentage of them that would be won by each player, and dividing the stakes in accordance with the ratio of these percentages.

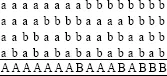

The situation is represented in Pascal's letter by the following tabular arrangement in which each column represents one possible outcome of the four games, with a representing a win of an individual game by A and b a win by B (Pascal actually used 1 s and 2s in the last row of the table where I have As and Bs, but this is irrelevant to the point of the discussion):

As this analysis shows, of the 16 possible outcomes of four games, A would win the series (by winning at least two individual games) in 11 cases and B (by winning at least three individual games) in 5. So, according to Fermat's reasoning, the stakes should be divided between A and B in the ratio 11 to 5.

Pascal argues that Fermat's analysis gives the correct answer, so long as there are only two players, but will not do so if there are more than two: “I must tell you that the solution of the problem of points for two players based on combinations is very accurate and true, but if there are more than two players it will not always be correct” (David, 1962, p. 240).

Before giving his reasons for believing Fermat's solution not to be reliable when there are more than two players, Pascal digresses to deal with an objection that a colleague, M. de Roberval, had raised to Fermat's solution, which Pascal had shown to him, even in the two—player case: “What is mistaken [according to de Roberval] is that the problem is worked out on the assumption that four games are played; in view of the fact that when one man wins two games or the other three, there is no need to play four games, it could happen that they would play two or three, or in truth, perhaps four” (David, 1962, p. 241).

In reporting to Fermat how he dealt with this objection, Pascal notes that he himself did not rely on the combinatorial method, “which in truth is not appropriate here,” but that nevertheless he was able to construct an argument that the method gave the correct answer in this case. First he made the point that if the two players, finding themselves in the situation that one needed two games to win the series and the other three, agreed to play four additional games, then Fermat's analysis shows the correct division of stakes. De Roberval agreed with this, but denied that it would apply if the players were not compelled to play the four games.

Pascal then argued that the continuation of play after one or the other has won the series—after A has won two games or B three—can have no effect on the outcome, so whether or not the players do continue is irrelevant:

Certainly it is easy to see that it is absolutely equal and immaterial to them both whether they let the game take its natural course, which is to cease play when one man has won, or to play the whole four games: therefore since these two procedures are equal and immaterial, the result must be the same in them both. Now, the solution is correct when they are obliged to play four games, as I have proved: therefore it is equally correct in the other case. (David, 1962, p. 242)

He does not say whether de Roberval was convinced.

Returning to the question of the applicability of Fermat's combinatorial analysis to cases in which there are more than two players, Pascal considers the following three—person situation. One player, whom I call A, needs one game to win and each of the other two, B and C, needs two. The maximum number of games that will be required to determine the winner is three, inasmuch as each of the 27 possible combinations of three wins contains either one win for A or two wins for either B or C. The problem, and the reason that Pascal dismisses the method, is that these are not mutually exclusive possibilities; some combinations contain more than one of them.

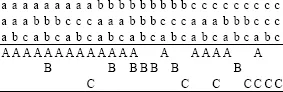

As before, Pascal represents the situation with a tabular arrangement in which each column identifies one possible outcome of three games:

So, given the need of A to win one game, and that of the other two players each to win two, the playing of three games will not invariably produce an unambiguous result. Pascal dismissed the possibility of simply adding up the total “wins” for each player and dividing the stakes in the proportion 19:7:7 on the grounds that a combination that is favorable to two players (e.g., abb) should not count as much for each of them as does a combination that is favorable to that player alone. One possibility that he considered is that of counting those combinations that are favorable to two players as half a win for each of them. This would give a division in the proportion 16:5.5:5.5.

Pascal argues that the latter solution would be fair if the players’ intention was to play three additional games and to share the winnings equally if there happened to be two winners, but not if their intention was to play only until the first player to reach his goal had done so. He contends that, given the second intention, the solution is unfair because it is based on the false assumption that three games will always be played. A similar assumption caused no difficulty in the two-person situation considered earlier, but it is problematic here. The difference between the situations is that in the first one a combination with more than one winner could not occur whereas in this one it could. Pascal goes on to say that if play is to be continued only until one of the players reaches the number of games he needs, the proper division is 17:5:5. This result, he says, can be found by his “general method,” which is not described in the letter.

In a reply to Pascal, dated Friday, September 25, 1654, Fermat agrees that the appropriate division in the three—person situation considered by Pascal is 17:5:5:

I find only that there are 17 combinations for the first man and 5 for each of the other two: for, when you say that the combination a c c is favourable to the first man and to the third, it appears that you forgot that everything happening after one of the players has won is worth nothing. Now since this combination makes the first man win the first game, of what use is it that the third man wins the next two games, because even if he won thirty games it would be superfluous? (David, 1962, p. 248)

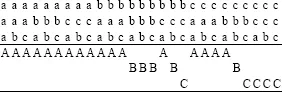

Fermat seems to be saying that if one uses his combinatorial analysis and credits a combination only to the first of the players to reach his goal, then one will get the right proportion in a straightforward way. If we do this with the previous table, for example, and let the top-to-bottom order of the rows represent the order in which the games are played, we get:

Fermat argues that this method is general in the sense that it works just as well no matter how many games are to be played. If it is done with four games, for example, it will be seen that A wins 51 of the 81 possible combinations and B and C each win 15, giving again the proportion 17:5:5. The tone of Fermat's letter suggests that he understood all this before Pascal pointed out the “problem” with his analysis of the two—person game.

Fermat proposes another way to view the situation. I quote his presentation of this view in its entirety, because it would be easy to change it subtly but materially by paraphrasing it:

The first man can win, either in a single game, or in two or in three.

If he wins in a single game, he must, with one die of three faces, win the first throw. [Throughout the correspondence Fermat and Pascal use the abstraction of an imaginary die with two or three faces.] A single [three—faced] die has three possibilities, this player has a chance of 1/3 of winning, when only one game is played.

If two games are played, he can win in two ways, either when the second player wins the first game and he wins the second or when the third player wins the first game and he wins the second. Now, two dice have 9 possibilities: thus the first man has a chance of 2/9 of winning when they play two games.

If three games are played, he can only win in two ways, either when the second man wins the first game, the third the second and he the third, or when the third man wins the first game, the second wins the second and he wins the third; for, if the second or third player were to win the first two games, he would have won the match and not the first player. Now, three dice have 27 possibilities: thus the first player has a chance of 2/27 of winning when they play three games.

The sum of the chances that the first player will win is therefore 1/3, 2/9 and 2/27 which makes 17/27.

And this rule is sound and applicable to all cases, so that without recourse to any artifice, the actual combinations in each number of games give the solution and show what I said in the first place, that the extension to a particular number of game...