Freshwater is scarce. It is a fundamental resource, part of all social and environmental processes. Freshwater sustains life. Yet freshwater systems are imperiled, and this threatens both human well-being and the health of ecological systems.

Although water is the most widely occurring substance on Earth, only 2.53 per cent is freshwater, while the remainder is saltwater. Some two-thirds of this freshwater is locked up in glaciers and permanent snow cover. In addition to the accessible freshwater in lakes, rivers and aquifers, human-made storage in reservoirs adds a further 8000 cubic kilometres (km3). Water resources are renewable, except for fossil groundwater. There are huge differences in availability in different parts of the world, and wide variations in seasonal and annual precipitation in many places.

Precipitation is the main source of water for all human uses and for ecosystems. Precipitation is taken up by plants and soils, evaporates into the atmosphere - in what is known as evapotranspiration - collects in rivers, lakes and wetlands, and runs off to the sea. The water of evapotranspiration (that is, the precipitation taken up by plants and soil) supports forests, cultivated and grazing lands, and ecosystems. Humans withdraw (for all uses including agriculture) 8 per cent of the total annual renewable freshwater, and appropriate 26 per cent of annual evapotranspiration and 54 per cent of accessible runoff. Humankind’s control of runoff is now global, and forms an important part of the hydrological cycle. Per capita use is increasing and the global population is growing. Together with spatial and temporal variations in available water, this leads to the consequence that water for all human uses is scarce. On a global scale, there is a freshwater crisis (UNESCO - WWAP, 2003).

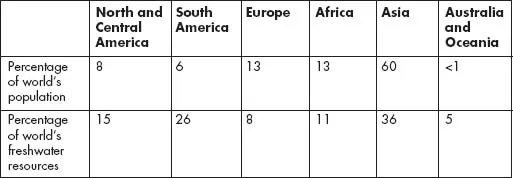

The available freshwater is distributed regionally as shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Regional distribution of renewable water availability and population

Source: UN-WWAP (2003)

Freshwater resources are further reduced by pollution. Some 2 million tonnes of waste per day are deposited in bodies of water, including industrial wastes and chemicals, human waste and agricultural wastes (fertilizers, pesticides and pesticide residues). Although reliable data on the extent and severity of pollution are incomplete, one estimate of global wastewater production is about 1500 km3 (UNESCO -WWAP, 2003). Assuming that 1 litre of wastewater pollutes 8 litres of freshwater, the present load of pollution may be up to 12,000 km3 worldwide. The poor are the worst affected, with 50 per cent of the population of developing countries being exposed to polluted water sources.

The precise impact of climate change on water resources is as yet uncertain. Precipitation will probably increase above latitudes 30°N and 30° S, but many tropical and sub-tropical regions will probably receive a lower and more unevenly distributed rainfall. Since there is a visible trend towards more frequent extreme weather conditions, it is likely that floods, droughts, mudslides, typhoons and cyclones will increase. Streamflows at low-flow periods may well decrease. Water quality will undoubtedly worsen because of increased pollution loads and concentrations, and higher water temperatures (Kunzewicz et al, 2007).

Good progress has been made in understanding the nature of water’s interaction with the biotic and abiotic environment. Better estimates of climate change impacts on water resources are available. Over the years, the understanding of hydrological processes has enabled humans to harvest water resources for their needs, reducing the risk of extreme situations. But pressures on the water system are increasing with population growth and economic development. Critical challenges lie ahead in coping with progressive water shortages and water pollution. According to the First World Water Development Report (UN-WWAP) (2003), by the middle of this century the number of people suffering from water shortages will be at worst 7 billion people in 60 countries, and even at best 2 billion people in 48 countries. Recent estimates suggest that climate change will account for about 20 per cent of the increase in global water scarcity.

1.1 WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT ISSUES - SOME PERSONAL EXPERIENCE

The many large-scale water resources projects I have been associated with have provided a rich source of knowledge and experience. Here are three examples, with a note of some of the lessons learned.

1.1.1 An integrated water resources model for Egypt

In the past, Egyptian water policies were formulated under the premise of the continued availability of ample surface freshwater. At that time, the clear policy choice was to develop water resources to the maximum extent possible. Financial and technological constraints were seen as the only limitation to such development. Economic feasibility was the main criterion for the approval of water resources projects. This meant that the analysis process used for policy formulation had well-defined aims. However, in order to meet the increasing demand for socio-economic development, the supply of surface water from the Nile had to be augmented with marginal-quality water and high-cost groundwater.

As Egyptian society strives to achieve a higher rate of economic growth, redistribution of the congested population in the Nile delta and valley, and environmental reclamation and protection, non-traditional strategies such as reallocation of water among the different uses, desalination of seawater, use of brackish water, mining of non-renewable groundwater and pollution control have had to be considered. Demand management strategies have become one of the main features of recent water policies.

To deal with integrated water management issues in Egypt, a new research group named the Nile Water Strategic Research Unit (NWSRU) has been established within the National Water Research Centre of Egypt (NWRC), through the second phase of the River Nile Protection and Development Project (RNPD-II, 1994). The NWSRU focuses on answering critical water resources development questions at all planning levels, with particular attention being given to future needs. Thus, a major task of the NWSRU is to apply a dynamic, interdisciplinary and multi-sectoral approach to modelling Egypt’s complex water resources.

Egypt’s share of the Nile’s water is 55.5 billion cubic metres per year (m3/yr). When this is distributed among the population, it barely reaches the water poverty threshold. To alleviate water poverty, other water resources have been made available through efforts such as the recycling of agricultural drainage. It is estimated that a volume of 4 billion m3/yr has been reclaimed through the reuse of agricultural drainage water in the Nile delta. Present extraction from the Nile aquifer is 4.8 billion m3/yr. While the agricultural sector consumes more than 80 per cent of the total water use, its contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) is only 20 per cent, which is very low when compared with the economic value of water in the industrial sector. Nevertheless, employment in the agriculture sector accounts for 40 per cent of the national labour power. Both sectors contribute to overall environmental degradation, and unlike agriculture, industry is a point source of water pollution and a major source of air pollution (see Figure 1.1, Plate 1).

The domestic demand for water accounts for less than 5 per cent of total water use, and about 20 per cent of the population have no access to safe drinking water. Losses in the distribution network are estimated to be around 50 per cent. Raising the distribution efficiency is expected to partially cover the predicted increase in domestic demand created by an increase in living standards and a growing population. Hydropower generation used to be considered as a consumptive use, but it is not seen in this light any longer, since water that generates power as it passes through the High Aswan Dam is not lost and can then be applied to other purposes. Navigation is another non-consumptive use that makes a significant contribution to the pollution of the Nile.

Note: A barrage is a hydraulic structure, a gated dam. Barrages were typically built on the River Nile or its branches with the purpose of elevating upstream water levels so that all the intakes into the branching irrigation canals were fed gravitationally. This old barrage on the Damietta branch is very close to the delta apex. It was built in 1863 to guarantee perennial irrigation of the delta without pumping. See Plate 1 for a colour version.

Source: photo courtesy of Dr Hussam Fahmy

Figure 1.1 An old barrage on the Damietta branch of the River Nile

Egyptian planners now consider sustainability and the environment in their planning, thereby increasing planning complexity beyond economic and engineering assessments. An Integrated Water Resources Model for Egypt (IWRME) has been developed, which uses the systems approach to analyse various policies and their long-term effects (Simonovic and Fahmy, 1999). The model relates various development plans in the different socio-economic sectors to water as a natural resource at the national (strategic) level. Agriculture, industry, domestic use, power generation and navigation are the five socio-economic sectors that depend directly on water. The model comprises six sectors: the five socio-economic sectors that depend on water, and the water sector itself.

The main objective behind the development of IWRME is to evaluate water policies formulated to satisfy long-term socio-economic plans at the national level in the five sectors. The time horizon of most socio-economic plans is from 25 to 30 years. Seven conventional and non-conventional water sources are modelled. Most of the water sources are conceptualized in the model as reservoirs with no maximum storage capacity. Based on the storage available in each one of them, there is a constraint on the level of withdrawal. The available storage depends mainly on the inflow to these reservoirs. In the case of desalination the inflow is infinite. In the case of surface water resources the inflow is finite, and is based on the releases from the High Aswan Dam, return flow from agriculture in Upper Egypt, and industrial and domestic effluent. On the timescale, a one-year model time increment has been chosen. No geographical distribution is assumed: that is, Egypt is modelled as a single geographical unit.

Because of the complexity of the model, gathering all the information from different sectors of the economy was not a simple process. To obtain the necessary information, it was necessary to exchange planning ideas about how to balance water demands with available resources. Discussions between the affected parties and the model developers enabled conflicting demands to be addressed and more realistic plans to be developed.

Accordingly, one of the activities of the NWSRU was to organize a workshop as a fo...