- 196 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Children Mourning, Mourning Children

About this book

Based on the Hospice Foundation of America's second annual teleconference, this book explores three basic themes in children's grief. Firstly, it maintains that children are always developing; therefore their understanding of death and their reactions to illness and loss are also multifaceted and constantly undergoing change. Secondly, children grieve in ways that are both different from and similar to adults. While they may need different therapeutic approaches from their elders, each loss is different and the grief experience will be affected by many of the same factors that affect adults. Thirdly, it holds that they need significant support as they grieve.; Talking to children about loss and and illness is too important to wait until a crisis; rather, it is essential to provide opportunities to discuss loss in times that are not so Emotionally Laden. This Book Aims To Demonstrate That Open Communication between parents and children will lead to skills and understanding that are essential to the child for coping with loss and reaffirming that death is part of the process of living.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Children Mourning, Mourning Children by Kenneth J. Doka in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

♦

Section Four

Innovative Research

Throughout this book, we have sought to include chapters that review the state of what is known and thought about children, life-threatening illness and death. There has been a concern that the author or each chapter provide an overview that is written in style that is concise and free of an overemphasis on research that might limit its accessibility to the broad viewership of this teleconference.

Yet, research is the lifeblood of a field. It allows its theories, ideas and programs to be evaluated and refined. It brings whole new areas and concepts into focus.

In editing this book, it seemed important to introduce readers to the interesting research that is currently being done and that underlies the chapters of this book and the focus of the teleconference. Of the existing material, three articles seemed particularly worthwhile to present to our readers.

Many viewers and readers have already been exposed to the work of Myra Bluebond-Langner whose book The Private Worlds of Dying Children (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978) remains a classic in the field. In that work, Bluebond-Langner suggests that children with a terminal illness gradually understand the implications of their disease.

But Bluebond-Langner has not only explored the worlds of dying children but also of their well siblings. In this piece, she points out that many of these children live in houses of chronic sorrow. Their own lives are often contingent on their sibling’s illness. And, Bluebond-Langner, reminds they often have to cope with their own confusing emotions while their parents’ focus may be engaged elsewhere. Bluebond-Langner’s article outlines a distinction so important in Anderson’s chapter. A disease may infect a certain number of people, but so many others are affected by it. And Bluebond-Langner sensitizes caregivers to the critical needs of these affected siblings.

Two other articles are included because they expand our thoughts about the nature of grief. McClowry and her associates challenge perspectives that grief is timebound and resolved in a similar way for each affected family. McClowry in her research found that parents who faced the death of a child lived with that sense of loss for long periods of time. While some felt they “got over it,” others described a more complex pattern where they found ways to fill this perpetual “empty space” or maintain a significant and therapeutic connection to the deceased child. It is not only adults that do that. Silverman, Nickman, and Worden, in their study of childhood bereavement also document the many ways that children continued a healthy sense of connection to their deceased parents.

Naturally this chapter is limited both by space and the editor’s own perception of significant researchers. Readers may wish to review the state of research themselves.

The bibliographies in the chapters should offer some direction. In addition, two journals, Omega and Death and Dying Studies are devoted exclusively to research on dying and death.

We wish to acknowledge permission to reprint the following articles:

From Death Studies, 1989, Vol. 13(1), pp.1–16,

“Worlds of Dying Children and Their Well Siblings,” by M. Bluebond-Langner Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved.

From American Journal of Ortho-psychiatry, Copyright 1992 by the American Orthopsychiatric Association, Inc.

“Detachment Revisited: The Child’s Reconstruction of a Dead Parent,” by Phyllis R. Silverman, Steven Nickman, and J. William Worden

From Death Studies, 1987, Vol. 11(5), pp. 361–374,

“The Empty Space Phenomenon,” by S.G. McClowry, E.B. Davies, K.A. May, E.J. Kulenkamp, and I.M. Martinson. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved.

10

Worlds of Dying Children and their Well Siblings

This paper examines the place of illness and death in the lives of healthy children and their ill siblings at the end stages of life. The behaviors that the children exhibit provide important insights into the children’s views of their lives as well as their views of death.

Introduction

A child is dying of kidney disease, of cystic fibrosis, of cancer. We refer to the child as a “victim of chronic or terminal illness.” But that child, that dying child, is not necessarily the only victim of chronic or terminal illness. The victims of chronic and terminal illness are not limited to the diagnosed patient. The destructive effects of such diseases spread to the families of those afflicted. New events and activities become part of the everyday lives of these families: time consuming care of the patient, trips to the hospital, the absence of family members during hospitalizations. A constant concern for the ill patient settles in for the duration. New feelings develop as well. Who would not occasionally resent the way in which one’s life has been complicated by capricious chance? Yet what right do the healthy members have to feel such feelings, to think such thoughts? They do not look forward to permanent disability or to death. So begins for the family, for each and every member of that family, a cycle of feelings that includes anxiety, guilt, neglect, denial, anger, and depression.

I want to call your attention to some of the other “victims”—the well siblings of terminally ill children dying of cancer and cystic fibrosis. I want to explore with you the place that illness and death have in their worlds. But before doing that, I think it is important to acquaint you with the world of the terminally ill child. For it is through observation and interaction with the dying child that the well sibling comes to know of disease and death. I will limit my remarks to the terminal phases of the illness. I will not discuss the behaviors one sees in earlier phases of the illness (e.g., diagnostic, relapses, exacerbations). The behaviors one sees before the child is terminal are very different from what one sees during the terminal phases. Later I will discuss some of those differences. For now, let us turn to the world of the terminally ill child.

Terminally Ill Children

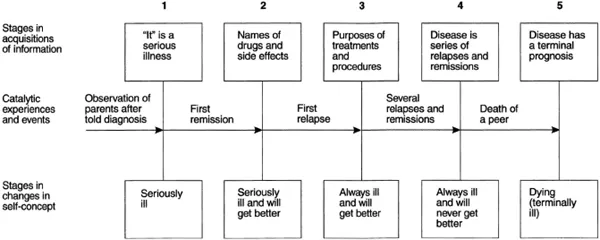

While all terminally ill children become aware of the fact that they are dying before death is imminent, the acquisition and assimilation of information is a prolonged process. It is a process that involves not only learning about the disease, but also experiences in that disease world and changes in self-concept. In situations where the children are told their diagnosis and prognosis, I refer to the process as one of internalization. In situations where the children are not told, I refer to the process as one of discovery. The process, however, remains the same in both situations and is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1

In the first stage in the acquisition of information, the children learn that they have a serious illness. In the second stage, they learn the name of the drugs and their side effects. In the third stage they become aware of the purposes of various treatments and procedures. In the fourth stage, they are able to take all of these isolated bits and pieces of information and put them into a larger perspective, the cycle of relapses and remissions. At this point, however, the children do not incorporate death into the cycle. It is only when they reach the fifth stage that the children come to see the disease as having a terminal prognosis.

At the same time that the children pass through these stages in the acquisition of information, their view of themselves also changes. They move from a view of themselves as seriously ill to a view of themselves as ill and going to get better, to a view of themselves as always ill and going to get better, to a view of themselves as always ill and never going to get better, and finally, to a view of themselves as dying.

For children to pass through these stages though, certain significant experiences have to take place. The first stage follows upon observation of their parents and the reactions of others to the news of the diagnosis. The second stage comes with the first remission; the third with the first relapse; the fourth, after a series of relapses and remissions; and the fifth, on the death of a peer.

As you consider this process, it is important to bear in mind that information is cumulative, such that if a child is at stage 2 and another child dies, he or she will not necessarily see the disease or himself or herself as having a terminal prognosis. Also, experience in the disease world is the most critical factor in the child’s coming to understand the disease. As you may have noticed, I have not mentioned age in this process. The children that we are going to be talking about are children between the ages of 5 and 12, all of whom became aware of the fact that they were dying before death was imminent. While their awareness of death did not vary by age, the way that they expressed it sometimes did.

If I had time, what I would like to do at this point is to detail each of the stages for you. But given the constraints of time, I’m going to jump to stage 4. At this point, the child, like the parents, comes to see the disease as something from which he or she will probably not recover. While the world is becoming increasingly closed to these children, they are still very much concerned about maintaining contact. The child is keenly aware of people’s exits and entrances. And perhaps that is why the death of a peer can have the impact that it does. It is as if in a matter of sentences the child assimilates a great deal of information and comes to the conclusion that he or she is dying. For example, a nurse had come into Tom’s room while he was sleeping to check his IV. On hearing her by his bed, Tom spoke.

Tom: Jennifer died last night. I have the same thing, don’t I?

Nurse: But they are going to give you different medicines.

Tom: What happens when they run out?

Nurse: Well, maybe they will find more before then.

This kind of conversation, of which I will give several examples, I refer to as a disclosure of awareness conversation. The conversation follows the same format regardless of what the other person in the interaction might say. The child begins by mentioning someone who has died or is in danger of dying. He or she then attempts to establish the cause of death either through a statement or a hypothesis. Finally, the child compares himself or herself to the deceased. For example:

Scott: You know Lisa?

Myra: [Nods.]

Scott: The one I played ball with. [Pause.] How did she die?

Myra: She was sick, sicker than you are now.

Scott: I know that. What happened?

Myra: Her heart stopped beating.

Scott [Hugging and crying]: I hope that never happens to me, but…

If the children recently discovered their prognosis, they talked about how different their condition was from that of the deceased, as in this conversation between a child I will call Benjamin and myself.

Benjamin: Dr. Richards told me to ask you what happened to Sylvia. [Dr. Richards had said no such thing.]

Myra: What do you think happened to Sylvia?

Benjamin: Well, she didn’t go to another hospital. Home?

Myra: No. She was sick, sicker than you are now, and she died.

Benjamin: She had nosebleeds. I had nosebleeds, but mine stopped.

Benjamin repeated this conversation with everyone he saw that day.

A more abstract version of a disclosure conversation occurred between a child I will call Stuart and myself after Stuart had been visited by a woman whose child had died 6 months earlier.

Stuart: Do you drive to the hospital?

Myra: No, I walk.

Stuart: Do you walk at night?

Myra [Noting the look on his face]: You wouldn’t?

Stuart: No, you would get shot. [Silence.] An ambulance would come and take you to the funeral home. And they would drain the blood out of you and wait 3 days and bury you.

Myra: That’s what happens when you die?

Stuart: I saw them do it to my grandmother.

Myra: I thought you told me you were here [in the hospital] when your grandmother died? [He was.]

Stuart [Quickly]: It was my grandmother. They wait 3 days to see if you’re alive. I mean, they draw the blood after they wait 3 days. [Note: the child had been in the hospital 3 days. They had drawn blood, done a bone marrow, and told the parents that things were not good, but that they would try one more experimental drug.] That’s what happens when you die. I’m going to get a new medicine put in me tonight.

If the child had known the prognosis for some time, he or she would talk about how much he or she was like the deceased, as in this conversation between a child I will call Mary, her mother, and an occupational therapy student when they were packing to go home.

OTS: What should I do with these, Mary? [Holding up the papers dolls that Mary, on an earlier occasion, said looked the way she did before she became ill.]

Mary [Who hadn’t said anything the entire time that they were packing to go home]: Put them in their grave in the Kleenex box.

Mother: Well, that’s the first thing you offered to do since the doctors said that we could go home.

Mary: I’m burying them. [Carefully arranges them between sheets of Kleenex.]

There were many children who did not engage in such full-blown disclosure of awareness conversations, but they made their awareness known in other ways. One way w...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- The Child's Perspective of Death

- Children' s Understandings of Death Striving to Understand Death

- Grieving Children Can We Answer Their Questions?

- The Child's Response To Life-Threatening Illness

- Talking to Children about Illness

- The Child and Life-Threatening Illness

- Children and HIV Orphans and Victims

- Children Mourning, Mourning Children

- Grief of Children and Parents

- Children and Traumatic Loss

- How Can We Help

- The Role of the School Bereaved Students & Students Facing Life-Threatening Illness

- Innovative Research

- Worlds of Dying Children and their Well Siblings

- Detachment Revisited The Child's Reconstruction of a Dead Parent

- The Empty Space Phenomenon The Process of Grief in the Bereaved Family

- A Sampler of Literature for Young Readers Death, Dying, and Bereavement

- Selected and Annotated Bibliographies

- Some Books to Guide Adults in Talking about Death with Children