eBook - ePub

Sustainable Investing

The Art of Long-Term Performance

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sustainable Investing

The Art of Long-Term Performance

About this book

Sustainable Investing is fast becoming the smart way of generating long-term returns. With conventional investors now scrambling to factor in issues such as climate change, this book captures a turning point in the evolution of global finance. Bringing together leading practitioners of Sustainable Investing from across the globe, this book charts how this agenda has evolved, what impact it has today, and what prospects are emerging for the years ahead. Sustainable Investing has already been outperforming the mainstream, and concerned investors need to know how best to position themselves for potentially radical market change.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sustainable Investing by Cary Krosinsky, Nick Robins, Cary Krosinsky,Nick Robins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Commerce & Investissements et valeurs mobilières. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Rise of

Sustainable Investing

____________________________

1

The Emergence of

Sustainable Investing

____________________________

THE ORIGIN OF THE SPECIES

It is said that it takes a generation for a potent idea to become common practice. In the case of sustainable development, it is now two decades since the Brundtland Commission first launched the concept onto the global stage, calling for a new pattern of growth that ‘meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (WCED, 1987). This poetically simple phrase contained within it three profound imperatives that challenged the prevailing models of economic performance: first, the identification of ecological constraints that human activity must respect (ecology); second, the concept of needs, particularly those of the poorest, to whom ‘utmost priority must be given’ in the commission's words (equity); and, third, the principle of intergenerational justice, adding a time dimension to the delivery of development so that long-term durability is not compromised by short-term speculation (futurity).

Looking back, the birth of sustainability was timely, coming as it did in the year that analysts believe that the global economy first entered a state of ecological debt – whereby resource extraction and pollution exceeds the carrying capacity of the planet, a deficit that has only deepened in succeeding years (WWF, 2007). Just as significant was its coincidence with the collapse of state communism, with the symbolic fall of the Berlin Wall, taking place just two years later. Critically, this meant that the realization of a sustainable economy would henceforth take place within the context of market-based capitalism. And if global capitalism is to become sustainable, then it makes sense to start with capital.

Yet, while some thought was given to the role that industry could play in the transition to sustainable patterns of development, the role of finance and investment was strangely absent, making investors the missing stakeholder in many subsequent negotiations to translate theory into practice. Indeed, when the then Business Council for Sustainable Development (BCSD) came to write its landmark report, Changing Course, for the 1992 Earth Summit, it acknowledged that ‘little is known about the constraints, the possibilities, and the interrelationships between capital markets, the environment, and the needs of future generations’ (BCSD, 1992; see also WBCSD, 1997). At the time, ethical investing was already practised by a growing number of individual and institutional investors in Europe and the US. But only a handful of the world's institutional investors had begun to include considerations of sustainability within their investment strategies. These included Bank Sarasin in Switzerland and Jupiter in the UK, both of which continue to be among the leading practitioners today. Nevertheless, a group of pioneers – led by Tessa Tennant and Mark Campanale in the UK, Peter Kinder in the US, Marc de Sousa Shields in Canada, and Robert Rosen in Australia – drafted the Rio Resolution, which sought to ‘draw to the attention of investors worldwide the link between investment policy and sustainable development’ (cited in Sparkes, 2002, p168).

Investment provides the bridge between an unsustainable present and a sustainable future – placing finance squarely at the heart of solutions to issues such as climate change and human rights. Across each of sustainability's three pillars of ecology, equity and futurity, the need for investment strategies that serve this transition is increasingly evident. Put simply, the world's capital markets fail to tell the ecological truth. According to Ernst von Weizsäcker: ‘the system of bureaucratic socialism can be said to have collapsed because it did not allow prices to tell the economic truth’ (von Weizsäcker, 1994). And despite the progress that has been made, he adds, ‘market prices are a long way from telling the ecological truth’. Negative environmental externalities remain significant, accounting for almost half of the US GDP, according to Redefining Progress (Talberth et al, 2006). In many cases, these externalities continue to grow. This is particularly stark in the case of climate change, where less than 10 per cent of global emissions are covered by carbon pricing mechanisms. Even where pricing has been introduced, this still undervalues the cost of greenhouse gas emissions, estimated by the Stern Review at some US$85 per tonne of carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent (Stern, 2006). Carbon has still only been marginally integrated within asset valuations. Thus, the share prices of oil, coal and gas companies remain buoyed up by the expected future returns from their reserves of fossil fuels, ignoring the huge carbon liability that is attached to each barrel of oil equivalent. As a result, hundreds of billions, if not trillions, of dollars in capital are still being routinely misallocated. Yet, in spite of these market failures, a growing body of sustainable investors have anticipated the future direction of policy and allocated increasing amounts of capital to environmental solutions.

In terms of equity, the challenge is for the investment industry to be an engine of social cohesion rather than social division. Much of today's investment industry has its roots in the post-war welfare settlement that gave rise to the modern pension and mutual fund industry (see, for example, Bogle, 2005). More recently, however, in a process described as ‘financialization’, a growing share of global output is taken by the finance sector and its employees. In the US, for example, finance-sector profits rose from 14 per cent in 1981 to 39 per cent of the total in 2001; over a similar timeframe – between 1980 and 2000 – average compensation for a US securities analyst tripled; for the average US worker, it doubled (Blackburn, 2006). Former investment banker Philip Augar has calculated that, as a result, US$120 billion was diverted from shareholders and customers to investment banking employees alone over the past two decades (Augar, 2006). Excessive remuneration and bonuses within the finance sector have attracted increasing public criticism not just for the social divisions that these create, but the perverse signals they often send for short-term profit-making. All of this has contributed to the wider rise in inequality, described as the emergence of a new Plutonomy by Ajay Kapur, until recently the chief global equity strategist at Citigroup (see Authers, 2007). In addition, the allocation of private capital for vital social infrastructure lags behind the surge in clean tech investing. As the unfolding sub-prime debacle in the US has demonstrated, conventional financial innovation has tended to progress without consideration of social impacts. The great challenge ahead is to harness the ingenuity of financial markets for social business, an issue addressed by Rod Schwartz in Chapter 12.

As for the core principle of futurity, the mainstream investment industry continues to foreshorten its time horizon when what is called for is the reverse. Technological innovation, financial deregulation and the rapid growth of hedge funds have served to make trading cheaper, easier and superficially more profitable – and so encourage short-term trading on the world's equity exchanges. In the UK, for example, the average holding period for shares on the London Stock Exchange has slumped from 9 years in 1986 to 11 months in 2006, suggesting that investors cannot wait between one annual report and the next before trading (Montier, 2005; see also Montier, 2007). Short-term performance measurement is a major profound driver of this behaviour, leading to extra costs and perverse results for the end investor. Indeed, there is a strong correlation between the time horizon of investment strategies and financial performance (see Chapter 2). Keynes's 70-year-old epitaph for the long-term investor still stands the test of time today. Writing in his groundbreaking General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money on the dynamics of investment practice, Keynes (1978) observed that ‘it is the long-term investor, he who most promotes the public interest, who will in practice come in for the most criticism wherever investment funds are managed by committees or boards or banks’.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE SPECIES

Since the embryonic initiatives of the early 1990s, sustainable investing has become one of the most creative areas of investment practice developing new ways of thinking and shaping an agenda for others to follow. It has attracted rapidly growing flows of assets and created new models for assessing fund performance. Many different streams have contributed to its rise. One of these is the pioneering ethical and socially responsible investment community, who first attempted to bring social and environmental values to the world's stock markets. In practice, ethical investing represents a merger between age-old principles of stewardship inherent to many of the world's religions and the more modern trend of ethical consumerism, as active individuals integrate their personal beliefs within their shopping and investing decisions.

Over the past 35 years, sustainable and responsible investing (SRI) has generally been characterized by the application of positive and negative screens to investment selection – on issues such as alcohol, environmental protection, gambling, human rights, military involvement, nuclear power, pornography and tobacco – as well as shareholder activism and community investing (see Domini and Kinder, 1986; Sparkes, 1995; Domini, 2001; Sparkes, 2002; Hudson, 2006; Kinder, 2007).

Equally important has been a host of new entrants who have responded to the investment challenges created by growing environmental constraints, increased public expectations of business social performance, new value drivers and heightened understanding of impacts up and down extended supply chains. Practitioners of sustainable investing share an interest in many of the same issues as ethical investors. But there are also important differences. While the primary spur for ethical investing is the internal value system of the investor, the prompt for sustainable investing is the external realities of an economy out of balance: water stress is thus not a question of belief, but of fact.

In essence, sustainable investors recognize that physical, regulatory, competitive, reputational and social pressures are driving environmental and social issues into the heart of market practice and thus the ability of companies to generate value for investors over the long term. Sustainable investors therefore incorporate these factors both within their choices over the selection and retention of investment assets and within the exercise of their ownership rights and responsibilities. It is this alignment with the forces shaping the planet that gives sustainable investors a far better chance of delivering outperformance than traditional investors. Indeed, much of the secret of sustainable investing's recent growth has been in its ability to sniff out critical trends before the ‘electronic herd’ of conventional investors, to stay one step ahead of the pack and to do things that seem to be eccentric at first, but then become perfectly normal. It was sustainable investors who first raised climate change as a financial issue, building understanding and expertise in advance of an often dismissive mainstream, who are now hastily playing catch-up. Matching this is the downside potential of anticipating trends too far ahead of the market – of being right too early.

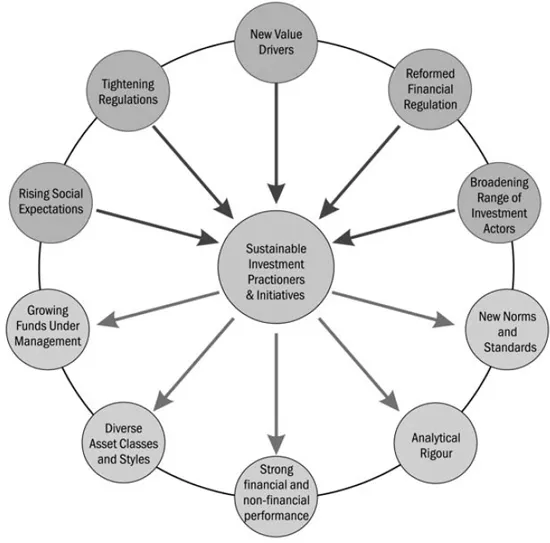

Source: Nick Robins

Figure 1.1 The dynamics of sustainable investment

Five main forces are at work in this arena, fusing with the efforts of sustainable investing pioneers to create tangible outcomes in terms of scale, diversity, financial and non-financial performance, analytical rigour and market norms (see Figure 1.1).

Rising social expectations around environmental protection, health and safety, and equal opportunities at work have formed the basis for a significant tightening in policy frameworks across the world during the past two decades. These have combined to create new value drivers for business success, where intangible assets have assumed ever greater importance. Thus, in the pre-sustainability mid 1980s, financial statements were capable of capturing 75 to 80 per cent of the risks and value creation potential of corporations. By the early 21st century, this had collapsed to less than 20 per cent (cited in Kiernan, 2007). Factors such as human capital and resource efficiency, along with brand and reputation are now critical to business success. Yet, mainstream investors have long ignored these and other issues, leaving it to the more nimble far-sighted sustainability investors to start the quest to understand the extra-financial aspects of performance. The financial success of many sustainability-focused funds at the end of the 1990s – such as NPI's Global Care range in the UK – helped to create the basis of evidence for amending financial regulation to reflect these new realities. Thus, in 2000, the UK introduced new requirements for pension fund trustees to consider the extent to which social, ethical and environmental factors were part of their investment strategies, paving the w...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures, Tables and Boxes

- List of Contributors

- Foreword by Steve Lydenberg

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- PART I — THE RISE OF SUSTAINABLE INVESTING

- PART II — CONFRONTING NEW RISKS AND OPPORTUNITIES

- PART III — SUSTAINABILITY ACROSS THE OTHER ASSET CLASSES

- PART IV — FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND TRENDS

- Glossary

- Appendix A: Sustainable and Responsible Initiatives and Resources

- Appendix B: Equity Returns Study Methodology –Determination of Annualized Five-Year Return for the Period 31 December 2002 to 31 December 2007

- Index