![]()

Chapter

1

THE CHARACTERISTICS OF SUNLIGHT

1.1 PARTICLE–WAVE DUALITY

Our understanding of the nature of light has changed back and forth over the past few centuries between two apparently conflicting viewpoints. A highly readable account of the evolution of quantum theory is given in Gribbin (1984). In the late 1600s, Newton's mechanistic view of light as being made up of small particles prevailed. By the early 1800s, experiments by both Young and Fresnel had shown interference effects in light beams, indicating that light was made up of waves. By the 1860s, Maxwell's theories of electromagnetic radiation were accepted, and light was understood to be part of a wide spectrum of electromagnetic waves with different wavelengths. In 1905, Einstein explained the photoelectric effect by proposing that light is made up of discrete particles or quanta of energy. This complementary nature of light is now well accepted. It is referred to as the particle-wave duality, and is summarised by the equation

where light, of frequency f or wavelength γ, comes in ‘packets’ or photons, of energy E, h is Planck's constant (6.626 × 10−34 Js) and c is the velocity of light (3.00 × 108 m/s) (NIST, 2002).

In defining the characteristics of photovoltaic or ‘solar’ cells, light is sometimes treated as waves, other times as particles or photons.

1.2 BLACKBODY RADIATION

A ‘blackbody’ is an ideal absorber, and emitter, of radiation. As it is heated, it starts to glow; that is, to emit electromagnetic radiation. A common example is when a metal is heated. The hotter it gets, the shorter the wavelength of light emitted and an initial red glow gradually turns yellow, then white.

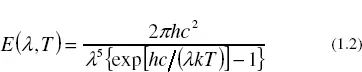

Classical physics was unable to describe the wavelength distribution of light emitted from such a heated object. However, in 1900, Max Planck derived a mathematical expression describing this distribution, although the underlying physics was not fully understood until Einstein's work on ‘quanta’ five years later. The spectral emissive power of a blackbody is the power emitted per unit area in the wavelength range λ to λ + d λ and is given by the Planck distribution (Incropera & DeWitt, 2002),

where k is Boltzmann's constant and E has dimensions of power per unit area per unit wavelength. The total emissive power, expressed in power per unit area, may be found by integration of Eqn. (1.2) over all possible wavelengths from zero to infinity, yielding E = σ T4, where σ is the Stefan– Boltzmann constant (Incropera & DeWitt, 2002).

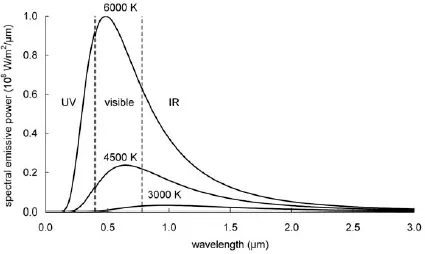

Figure 1.1. Radiation distributions from perfect blackbodies at three different temperatures, as would be observed at the surface of the blackbodies.

Fig. 1.1 illustrates the radiation distribution for different blackbody temperatures, as would be observed at the surface of the blackbody. The lowermost curve is that for a body heated to 3000 K, about the temperature of the tungsten filament in an incandescent lamp. The wavelength of peak energy emission is about 1 μm, in the infrared. Only a small amount of energy is emitted at visible wavelengths (0.4–0.8 μm) in this case, which explains why these lamps are so inefficient. Much higher temperatures, beyond the melting points of most metals, are required to shift the peak emission to the visible range.

1.3 THE SUN AND ITS RADIATION

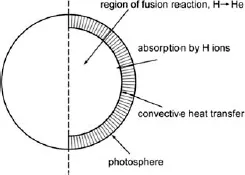

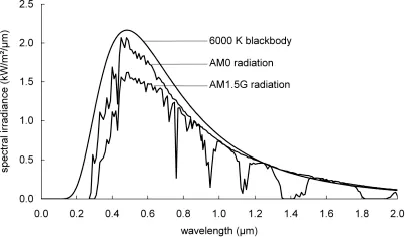

The sun is a hot sphere of gas heated by nuclear fusion reactions at its centre (Quaschning, 2003). Internal temperatures reach a very warm 20 million K. As indicated in Fig. 1.2, the intense radiation from the interior is absorbed by a layer of hydrogen ions closer to the sun's surface. Energy is transferred by convection through this optical barrier and then re-radiated from the outer surface of the sun, the photosphere. This emits radiation approximating that from a blackbody with a temperature of nearly 6000 K, as shown in Fig. 1.3.

Figure 1.2. Regions in the sun's interior.

Figure 1.3. The spectral irradiance from a blackbody at 6000 K (at the same apparent diameter as the sun when viewed from earth); from the sun's photosphere as observed just outside earth's atmosphere (AM0); and from the sun's photosphere after having passed through 1.5 times the thickness of earth's atmosphere (AM1.5G).

1.4 SOLAR RADIATION

Although radiation from the sun's surface is reasonably constant (Gueymard, 2004; Willson & Hudson, 1988), by the time it reaches the earth's surface it is highly variable owing to absorption and scattering in the earth's atmosphere.

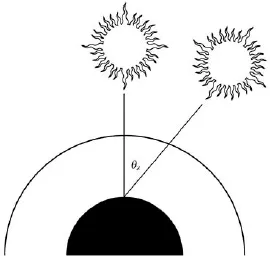

When skies are clear, the maximum radiation strikes the earth's surface when the sun is directly overhead, and sunlight has the shortest pathlength through the atmosphere. This pathlength can be approximated by 1/cosθz, where θz is the angle between the sun and the point directly overhead (often referred to as the zenith angle), as shown in Fig. 1.4. This pathlength is usually referred to as the air mass (AM) through which solar radiation must pass to reach the earth's surface. Therefore

This is based on the assumption of a homogeneous, non-refractive atmosphere, which introduces an error of approximately 10% close to the horizon. Iqbal (1983) gives more accurate formulae that take account of the curved path of light through atmosphere where density varies with depth.

Figure 1.4. The amount of atmosphere (air mass) through which radiation from the sun must pass to reach the earth's surface depends on the sun's position.

When θz = 0, the air mass equals 1, or ‘AM1’ radiation is being received; when θz = 60°, the air mass equals 2, or ‘AM2’ conditions prevail. AM1.5 (equivalent to a sun angle of 48.2° from overhead) has become the standard for photovoltaic work.

The air mass (AM) can be estimated at any location using the following formula:

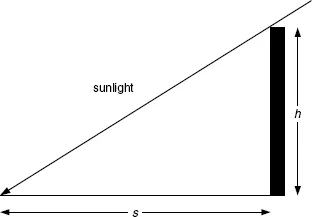

where s is the length of the shadow cast by a vertical post of height h, as shown in Fig. 1.5.

Figure 1.5. Calculation of Air Mass using the shadow of an object of known height.

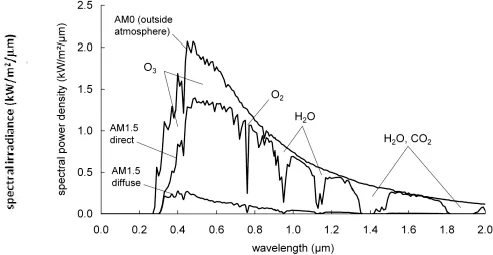

The spectral distributions of the sun's irradiance outside the atmosphere (Air Mass Zero or AM0), and at AM1.5 are shown in Fig. 1.6. Air Mass Zero is essentially unvarying and its total irradiance, integrated over the spectrum, is referred to as the solar constant, with a generally accepted value (ASTM, 2000, 2003; Gueymard, 2004) of

Figure 1.6. The spectral irradiance of sunlight, outside the atmosphere (...