![]()

Chapter 1

The Affect Heuristic and the Attractiveness of Simple Gambles

Ian Bateman, Sam Dent, Ellen Peters, Paul Slovic and Chris Starmer*

Introduction

The gamble has been to decision research what the fruit fly has been to biology – a vehicle for examining fundamental processes with presumably important implications outside the laboratory. Judgement and decision researchers have been studying people's preferences among gambles for more than 50 years. This chapter will describe a series of experiments with gambles that add to the growing literature on preference construction (Lichtenstein and Slovic, 2006) and provide what we hope are useful insights about the interplay of affect, reason, risk and rationality in life's most important gambles.

In recent years there has been much interest in using the concept of affect to understand a wide range of decision behaviours (Loewenstein et al, 2001; Slovic et al, 2002; Peters et al, 2006a). In this chapter, experimental studies with simple gambles are used to examine the roles of affect and the related concept of evaluability in determining judgements and decisions. We begin by providing some theoretical background on the key concepts. We next describe experiments demonstrating an anomalous finding: introducing a small loss as a component of a gamble increases its attractiveness. We then hypothesize an explanation for this anomaly based upon affect and describe several experiments that test and confirm this hypothesis. Finally, we discuss evidence that the subtle, context-dependent valuations we have observed with gambles in simple laboratory experiments appear to occur as well in many types of important decisions outside the laboratory.

Background and theory: The importance of affect

In this chapter, following Slovic et al (2002), we use the term affect to refer to experienced feeling states associated with positive or negative qualities of a stimulus. Slovic et al (2002) present a wide range of evidence supporting the notion that images, marked by positive and negative affective feelings, guide judgement and decision making. In light of this evidence, they propose that people use an affect heuristic to make judgements. That is, in the process of making a judgement or decision, people consult or refer to the positive and negative feelings consciously or unconsciously associated with the mental representations of the task. Then, just as imaginability, memorability and similarity serve as cues for probability judgements (e.g. the availability and representativeness heuristics), affect may also serve as a cue for many important judgements and decisions (Kahneman, 2003). Affective responses tend to occur rapidly and automatically. As such, using an overall, readily available affective impression can be quicker and easier – and thus sometimes more efficient – than weighing the pros and cons or retrieving relevant examples from memory, especially when the required judgement or decision is complex or cognitive resources are limited.

The concept of evaluability has been proposed as a mechanism mediating the role of affect in decision processes. Affective impressions vary not only in their valence, positive or negative, but in the precision with which they are held. There is growing evidence that the precision of an affective impression substantially impacts judgements. In particular, Hsee (1996a, b, 1998) has proposed the notion of evaluability to describe the interplay between the precision of an affective impression and its meaning or importance for judgement and decision making. Evaluability is illustrated by an experiment in which Hsee (1996b) asked people to assume they were looking for a used music dictionary. In a joint-evaluation condition, participants were shown two dictionaries, A (with 10,000 entries in ‘like new’ condition) and B (with 20,000 entries and a torn cover), and were asked how much they would be willing to pay for each. Willingness-to-pay was far higher for Dictionary B, presumably because of its greater number of entries. However, when one group of participants evaluated only A and another group evaluated only B, the mean willingness to pay was much higher for Dictionary A. Hsee explains this reversal by means of the evaluability principle. He argues that, in separate evaluation, without a direct comparison, the number of entries is hard to evaluate, because the evaluator does not have a precise notion of how good 10,000 (or 20,000) entries is. However, the defects attribute is evaluable in the sense that it translates easily into a precise good/bad response and thus it carries more weight in the independent evaluation. Most people find a defective dictionary unattractive and a ‘like-new’ dictionary attractive. Under joint evaluation, the buyer can see that B is far superior on the more important attribute, number of entries. Thus the number of entries becomes evaluable through the comparison process.

According to the evaluability principle, the weight of a stimulus attribute in an evaluative judgement or choice is proportional to the ease or precision with which the value of that attribute (or a comparison on the attribute across alternatives) can be mapped into an affective impression. In other words, affect bestows meaning on information (cf. Osgood et al, 1957; Mowrer, 1960a, b) and the precision of the affective meaning infiuences our ability to use information in judgement and decision making. Evaluability can thus be seen as an extension of the general relationship between the variance of an impression and its weight in an impression-formation task (Mellers et al, 1992).

Hsee's work on evaluability is noteworthy because it shows that even very important attributes may not be used by a judge or decision maker unless they can be translated precisely into an affective frame of reference. The implications of these findings may be quite wide-ranging: Hsee (1998) demonstrates evaluability effects even with familiar attributes such as the amount of ice cream in a cup. Slovic et al (2002) demonstrate similar effects with decisions about options saving different numbers of human lives.

Evaluability and the attractiveness of gambles

In this section we propose evaluability as an explanation for some early findings in the judgement and decision literature pertaining to gambles. In subsequent sections we shall discuss a series of newer studies, also conducted with gambles, which test this explanation.

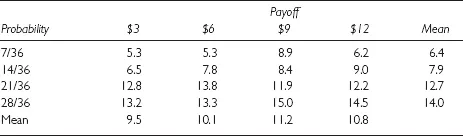

A number of studies have found that attractiveness ratings of simple gambles are influenced more by probabilities than by payoffs. Evidence for this claim can be found in Slovic and Lichtenstein (1968a), Goldstein and Einhorn (1987), Schkade and Johnson (1989) and, more recently, in data from a pilot study conducted by the present authors at the University of Oregon. In this pilot study, the relative importance of probabilities and payoffs was evaluated with 16 gambles, created by crossing four levels of winning probability (7/36, 14/36, 21/36 and 28/36) with four levels of payoff ($3, $6, $9, $12). University of Oregon students (N = 297) were randomly assigned to one of the 16 gambles and were asked to rate its attractiveness on a 0 (not at all attractive) to 20 (extremely attractive) scale. The mean ratings, shown in Table 1.1, indicated that attractiveness increased monotonically as probability increased, with the largest (and statistically significant differences) occurring when the two highest probabilities (21/36 and 28/36) were compared with the two lowest (7/36 and 14/36). Mean attractiveness varied little across a fourfold increase in payoffs (no column mean differences were significant statistically). A subsequent study using the same probabilities but increasing the payoffs to $30, $60, $90, and $120 showed essentially the same weak influence of payoff.1

The concept of evaluability provides one possible interpretation of these results. Following Hsee's reasoning one may argue that, because probabilities are represented on a fixed scale from 0 to 1, they can be more readily mapped into a relatively precise affective response: a probability close to zero can readily be interpreted as a ‘poor’ chance to win. By contrast, payoff outcomes such as those in Table 1.1 have less obvious affective connotations, at least in the absence of further context. To illustrate the point, ask yourself the question ‘how good is $9’? This $9 question, we contend, has no clear answer without further context. For instance, while it may be difficult to evaluate the goodness of an abstract and context-free $9, when further context is provided, the same amount of money may then ‘come alive with feeling’ (Slovic et al, 2002). For instance, although a $9 tip on a $30 restaurant bill may immediately be judged good by a waiter, a $9 increase on a monthly salary of $2000 may be judged quite negatively by an employee. If it is accepted that, in the context of these studies, probabilities are more evaluable than monetary outcomes, evaluability implies that attractiveness ratings will be relatively more sensitive to probabilities than to payoffs.2

Table 1.1 Mean attractiveness ratings in the pilot study

Note: Each respondent saw one probability/payoff combination (e.g. 14 chances out of 36 to win $6) and was asked to rate the attractiveness of playing this gamble on a 0 (not at all attra...