![]()

Part I:

Introduction

![]()

1

For Whom the Bell Tolls:

Vulnerabilities in a Changing Climate

Neil Leary, James Adejuwon, Wilma Bailey, Vicente Barros, Punsalmaa Batima, Rubén M. Caffera, Suppakorn Chinvanno, Cecilia Conde, Alain De Comarmond, Alex De Sherbinin, Tom Downing, Hallie Eakin, Anthony Nyong, Maggie Opondo, Balgis Osman-Elasha, Rolph Payet, Florencia Pulhin, Juan Pulhin, Janaka Ratnisiri, El-Amin Sanjak, Graham von Maltitz, Mónica Wehbe, Yongyuan Yin and Gina Ziervogel

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

JOHN DONNE, 1623

Introduction

People have evolved ways of earning livelihoods and supplying their needs for food, water, shelter and other goods and services that are adapted to the climates of the areas in which they live. But the climate is ever variable and changeable, and deviations that are too far from the norm can be disruptive, even hazardous.

Now the climate is changing due to human actions. Despite efforts to abate the human causes, human-driven climate change will continue for decades and longer (IPCC, 2001a). Who is vulnerable to the changes and their impacts? For whom does the bell toll? We ask, against the oft-quoted advice of the poet John Donne, because understanding who is vulnerable, and why, can help us to prevent our neighbour’s home from washing into the sea, a family from suffering hunger, a child from being exposed to disease and the natural world around us from being impoverished. All of us are vulnerable to climate change, though to varying degrees, directly and through our connections to each other.

The propensity of people or systems to be harmed by hazards or stresses, referred to as vulnerability, is determined by their exposures to hazard, their sensitivity to the exposures, and their capacities to resist, cope with, exploit, recover from and adapt to the effects. Global climate change is bringing changes in exposures to climate hazards. The impacts will depend in part on the nature, rate and severity of the changes in climate. They will also depend to an important degree on social, economic, governance and other forces that determine who and what are exposed to climate hazards, their sensitivities and their capacities. For some, the impacts may be beneficial. But predominantly harmful impacts are expected, particularly in the developing world (IPCC, 2001b).

To explore vulnerabilities to climate change and response options in developing country regions, 24 regional and national assessments were implemented under the international project ‘Assessments of Impacts and Adaptations to Climate Change’ (AIACC). The case studies, executed over the period 2002–2005, are varied in their objectives, geographic and social contexts, the systems and sectors that are investigated, and the methods that are applied. They are located in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and islands of the Caribbean, Indian and Pacific Oceans. The studies include investigations of crop agriculture, pastoral systems, water resources, terrestrial and estuarine ecosystems, biodiversity, urban flood risks, coastal settlements, food security, livelihoods and human health.

One factor that is common to most of the studies is that they include investigation of the vulnerability of people, places or systems to climatic stresses. Vulnerability studies take a different approach from investigations of climate change impacts. The latter generally emphasize quantitative modelling to simulate the impacts of selected climate change scenarios on Earth systems and people. By contrast, vulnerability studies focus on the processes that shape the consequences of climate variations and changes to identify the conditions that amplify or dampen vulnerability to adverse outcomes. The climate drivers are treated as important in vulnerability studies, but drivers related to demographic, social, economic and governance processes are given equal attention. Understanding how these processes contribute to vulnerability and adaptive capacity in the context of current climate variations and extremes can yield insights regarding vulnerability to future climate change that can help to guide adaptive strategies (Leary, 2002).

This volume presents a collection of papers from the AIACC case studies that address questions about the nature, causes and distribution of vulnerability to climate change. In this first chapter we introduce the case studies and present a synthesis of lessons from our comparison of the studies. A companion to this volume, Climate Change and Adaptation (Leary et al, 2008), explores options for adapting to climate change, capacities for implementing these and obstacles to be overcome.

Our synthesis of lessons about vulnerability is a product of a week-long workshop held in March 2005. During the workshop we applied a three-step risk assessment protocol previously used by Downing (2002). In the first step we identified domains of vulnerability that correspond to resources or systems that are important to human well-being, are very likely to be affected by climate change, and are a focus of one or more of the case studies. Four major domains were selected, around which we organized our discussions in the workshop and which have been used to structure both this chapter and the book as a whole: 1) natural resources, 2) coastal areas and small islands, 3) rural economy and food systems, and 4) human health.

In the second step, outcomes of concern within each domain were identified and ranked as low-, medium- or high-level concerns. In selecting and ranking outcomes, we attempted to take the perspective of stakeholders concerned about national-scale risks. Outcomes are included that our studies and our interpretation of related literature suggest are plausible, and that would be of national significance should they occur. Our rankings of low-, medium- and high-level concerns are based on the following criteria: potential to exceed coping capacities of affected systems, the geographic extent of damages, the severity of damages relative to national resources, and the persistence versus reversibility of the impacts. The rankings do not take into account the likelihood that an outcome would be realized. They represent the degree of concern that would result if the hypothesized outcomes do materialize. While we have not formally assessed the likelihood of the different outcomes, each is a potential result under plausible scenarios and circumstances.

In step three we identified the climatic and non-climatic factors that create conditions of vulnerability to the outcomes of concern within each domain. Where climatic and non-climatic drivers combine to strongly amplify vulnerability, the potential for high-level concern outcomes being realized is greatest. Conversely, where some of the drivers interact to dampen vulnerability, outcomes of lower-level concern are likely to result.

The lessons produced from this protocol are presented below in this chapter. The case studies from which they are derived are elaborated on in the chapters that follow.

Natural Resources

Natural resources, under pressure from human uses, have undergone rapid and extensive changes over the past 50 years that have resulted in many of them being degraded (MEA, 2005). Population and economic growth are likely to intensify uses of and pressures on natural resource systems. Global climate change, which has already impacted natural resource systems across the Earth, is adding to the pressures and is expected to substantially disrupt many of these systems and the goods and services that they provide (IPCC, 2001b; IPCC, 2007; MEA, 2005). Our case studies investigated vulnerabilities to climate hazards for a variety of natural resources, which are grouped into the contexts of water, land, and ecosystems and biodiversity.

Water

Population and economic growth are increasing water demands, and many parts of the world are expected to face increased water stress as a result (Arnell, 2004). Water resources are highly sensitive to variations in climate and, consequently, climate change will pose serious challenges to water users and managers (IPCC, 2001b). Climate change may exacerbate the stress in some places but ameliorate it in others, depending on the changes at regional and local levels.

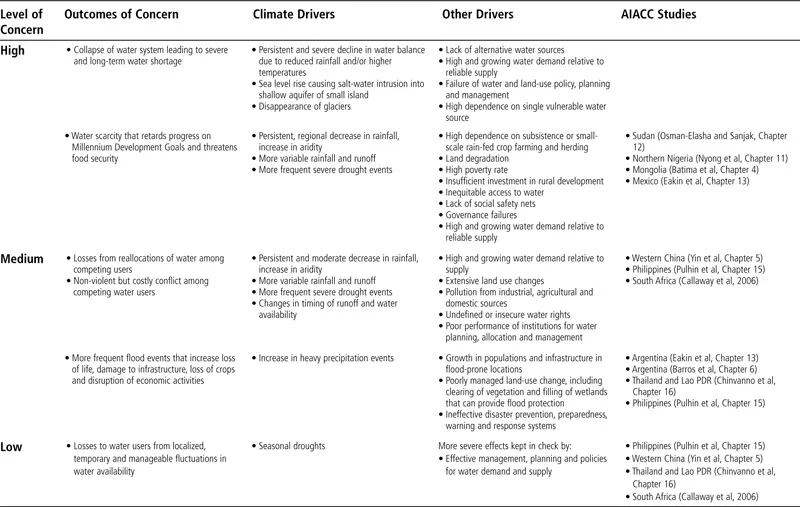

Vulnerabilities from water resource impacts of climate change are addressed by several of the case studies. Outcomes of concern for water resources from these studies and the climatic and non-climatic drivers of the outcomes are identified in Table 1.1. Scenarios of future climate change indicate that many of the study regions, including parts of Africa and Asia, face risks of greater aridity, more variable water supply and periods of water scarcity from drought. In contrast, scenarios suggest that the climate may become wetter and water supply greater in southeastern South America and southeastern Asia.

Changes in water balances will impact land, ecosystems, biodiversity, rural economies, food security and human health; vulnerabilities to these impacts are discussed in later sections of this chapter. The outcomes are strongly dependent on factors such as the level and rate of growth of water demands relative to reliable supplies; water and land-use policies, planning and management; water infrastructure; and the distribution and security of water rights. Where water becomes less plentiful and climates drier, the changes have the potential to retard progress towards the Millennium Development Goals.

The impacts that can result from persistent and geographically widespread declines in water balances have been demonstrated all too frequently. Osman-Elasha and Sanjak (Chapter 12) and Nyong et al (Chapter 11) examine the impacts of decades of below average rainfall and recurrent drought in two parts of the Sudano-Sahel zone with case studies in Sudan and Nigeria respectively. The reduced availability of water in these arid and semi-arid areas has resulted in decreased food production, loss of livestock, land degradation, migrations from neighbouring countries and internal displacements of people. The effects of water scarcity have contributed to food insecurity and the destitution of large numbers of people; they are also implicated as a source of conflict that underlies the violence in Darfur.

Non-climate factors that have contributed to the severity of impacts of past climatic events in Sudan and Nigeria create conditions of high vulnerability to continued drying of the climate and future drought. Both studies find that large and growing populations in dry climates that are highly dependent on farming and grazing for livelihoods, lack of off-farm livelihood opportunities, reliance of many households on marginal, degraded lands, high poverty levels, insecure water rights, inability to economically and socially absorb displaced people, and dysfunctional governance institutions create conditions of high vulnerability to changes in water balances. While projected water balance changes for the Sahel and Sudano-Sahel zones are mixed (Hoerling et al, 2006), they include worrisome scenarios of a drier, more drought-prone climate for these regions.

Table 1.1 Water resource vulnerabilities

The Heihe river basin of northwestern China has experienced more modest drying over the past decade (Yin et al, Chapter 5). But with increasing development in the basin, water demands have been rising and intensifying competition for the increasingly scarce water. As a result, water users in the basin have become more vulnerable to water shortage, reduced land productivity and non-violent conflict over water allocations. These effects illustrate outcomes of medium- and low-level concern. A drier climate, as some scenarios project for the region, would exacerbate these conditions and could result in outcomes of higher-level concern if future development in the basin raises water demand beyond what can be supplied reliably and sustainably.

For the case study regions in the eastern part of the southern cone of South America (Conde et al, Chapter 14; Eakin et al, Chapter 13; Camilloni and Barros, 2003), the Philippines (Pulhin et al, Chapter 15), and the Lower Mekong river basin (Chinvanno et al, Chapter 16), climate change projections suggest a wetter climate and increases in water availability. In the southern cone of South America, increased precipitation over the past two decades has contributed to the expansion of commercially profitable rain-fed crop farming, particularly of soybeans, into cattle ranching areas that were previously too dry for cropping. While this has generated significant economic benefits, the increased rainfall has also brought losses from increases in heavy rainfall and flood events. In the future, a wetter climate in these regions would also bring benefits from increased water availability, but may cause damages from flooding and water-logging of soils (Eakin et al, Chapter 13). Furthermore, farmers may face greater risks from greater rainfall variability in South America that could include both heavier rainfall events and more frequent droughts (IPCC, 2001a).

In the Pantabangan–Carranglan watershed of the Philippines, increases in annual rainfall and water runoff would benefit rain-fed crop farmers, irrigators, hydropower generators and other water users. But changes in rainfall variability, including those related to changes in ENSO variability, could intensify competition for water among upland rain-fed crop farmers, lowland irrigated crop farmers, the National Power Corporation and the National Irrigation Administration (Pulhin et al, Chapter 15). Changes in flood risks are also of concern in the watershed. In the Lower Mekong, while increases in annual rainfall may bring increases in average rice yields, shifts in the timing of rainy seasons and the potential for more frequent flooding are found to pose risks for rice farmers (Chinvanno et al, Chapter 16). Those most vulnerable to changes in variability in the Lower Mekong and in Pantabangan–Carranglan are small-scale farmers with little or no land holdings, lack of secure water rights, limited access to capital and other resources, and limited access to decision-making processes.

Land

The quality and productivity of land is strongly influenced by climate and can be degraded by the combined effects of climate variations and human activities. Land degradation has become one of the most serious environmental problems, reducing the resilience of land to climate variability, degrading soil fertility, undermining food production and contributing to famine (UNCCD, 2005a)....