![]()

Section II

Empirical Studies of Public Engagement

![]()

Part 1

STAKEHOLDER AND MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT

![]()

Chapter 6

Discourses on the Implementation of Wind Power: Stakeholder Views on Public Engagement

Maarten Wolsink

Introduction

A crucial dimension of the context of institutional key variables that can be held responsible for the variation in implemented wind power capacity is how actors with different stakes perceive the deployment of wind power. Among key stakeholders, very strong conflicts between views exist. These conflicts are linked with the positions that actors hold within the domain of wind power development, and they concern all aspects of implementation. Among these are the financial procurement system and government policies, but they also concern the engagement of civil society in wind power schemes.

In an international comparative study in three countries on the institutional setting of wind power implementation (Breukers, 2007) the current discourses among all key actors involved in the implementation process were investigated, as these perspectives can be related to the historical-institutional legacy of the geographical cases. For that purpose the Q method was used; this is a formal reconstructive methodology which measures quantified unique responses to stimuli, allowing for a qualitative evaluation and comparison of human subjectivity. The complete patterns of stakeholder views, as reported in Wolsink and Breukers (2010) include all aspects that were marked as significant by the stakeholders themselves.

Involvement in Wind Power Schemes

In the case of wind power, the domains of significant stakeholders are energy policy, spatial planning and environmental policy. Here we focus on the views of stakeholders from these domains concerning the engagement of civil society in wind power schemes, which mainly concerns planning regimes and decision-making about projects. Planning systems in most countries, although very different, apparently all seem to have difficulty with decisions over wind power; they almost seem ‘designed to fail’ (Wolsink, 2009). The starting point is often that developers, authorities or hired experts need to do nothing more than present information to the still ignorant local civilians. Most studies on decision-making show, in fact, that developers and their associates urgently need to be informed, for example, about the crucial role of factors of community and landscape identity, and how to deal with the culturally rooted and fundamental subjectivity of these. Usually their knowledge about this is limited, and understanding of how to include the community values in decision-making on wind farms is mostly not supported by existing planning procedures. Planning systems and planning agencies have difficulty in incorporating landscape valuation because of its subjectivity and the variation of this subjectivity. As ‘knowledge’ about landscape valuation is in ‘the eye of the beholder’ (Lothian, 1999), ultimately the people who identify themselves with the landscape (‘place identity’) are the ‘experts’. At the same time, landscape is the most important attribute in shaping attitudes towards wind energy projects (Wolsink, 2007) and therefore community involvement in the development of wind power schemes is crucial.

Unfortunately, planning systems are seldom designed to handle the required involvement of civil society; in fact they are often designed to avoid this kind of involvement. The reaction of governments to adapting planning systems to deal with the ‘obstacle course’ caused by developers seems to be merely a reinforcement of that design (for example, in the UK; Ellis et al, 2009; Haggett, 2009, p304). Do these efforts reflect the views of all key stakeholders? In particular, do they reflect the views of those who have experience of successful implementation, and if not, what are their perspectives? This analysis of patterns in stakeholder views reveals that strong dissimilarities exist in perspectives on planning and on the need for involvement and participation.

Research Approach

In a geographical study of onshore wind power developments in The Netherlands, North Rhine–Westphalia (NRW) and England, the institutional conditions and changes in the domains of energy policy, spatial planning and environmental policy were compared with respect to how they influenced the clear differences in the implementation rates of wind power in those countries (Breukers and Wolsink, 2007). A crucial dimension of the institutional context is how key actors with different interests perceive the realization of wind power projects. These perspectives on implementation processes and considerations about economics, spatial planning and the environment are defined as the current stakeholder positions in ongoing environmental discourses (Dryzek, 2005). To reveal the common narratives, representatives of all key stakeholder groups in the relevant policy domains were identified and interviewed. In this ‘P sample’ (in the method applied to be distinguished from the ‘Q sample of statements; see below), all levels of governance from local to national were included (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 Samples of respondents representing stakeholders (2003–2005)

|

Stakeholder category | North Rhine–Westphalia | England | The Netherlands |

|

Local, regional, national governments and agencies | 7 | 6 | 5 |

Citizen projects, cooperations | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Private wind project developers | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Anti-wind power groups | 1 | 2 | 1 |

Environment/nature protection/landscape preservation organizations | 3 | 5 | 2 |

Wind power/renewables branches | 4 | 2 | 4 |

Conventional energy sector | 1 | 2 | 2 |

Researchers | 1 | 1 | 1 |

N (total N=56) | 20 | 19 | 17 |

|

These interviews started with collecting the data for the Q study. Q methodology provides a structural model that measures quantified unique responses to stimuli (a set of statements) that allow for a qualitative evaluation and comparison of human subjectivity. The method has been applied in a study of decision-making on wind power (Ellis et al, 2007), but it can also be applied as a tool to support public participation itself (Doody et al, 2009). Similarities between individual views make it possible to articulate a condensed number of social narratives on a topic (Webler et al, 2001). Unlike surveys and interviews, it bypasses the researcher, because the patterns that are revealed by the analysis are produced by the respondents and not by the analysing researcher (Eden et al. 2005). It allows ‘the categories of the analysis to be manipulated by respondents’ (Robbins and Krueger, 2000, p645). Explications of the technique can be found in Stenner et al (2008) and McKeown and Thomas (1988). The entire procedure and full results on all aspects of wind energy implementation are described in Wolsink and Breukers (2010), but here we emphasize the essential contrasts in the views on community involvement and focus on how the presented data can be interpreted.

The first step was to formulate and select a set of 60 statements (the ‘Q sample’) that would represent the entire opinion domain. The statements included all the possible diverse viewpoints on all sub-themes present within the realm of the topic. They were spread over the following categories:

• arrangements within the policy domains of energy and environment;

• the role, position and objectives of the incumbents in the energy sector, in particular existing energy companies; and

• financial support regimes and their stability.

These categories are not directly associated with the involvement of the public. The following categories, however, are all directly linked with issues of public involvement:

• The impact of spatial planning and of location decision-making. Political institutions that do not support local collaborative approaches and that do not allow the community to negotiate on the impact on the landscape reduce the success of national wind power programmes. These negotiations concern the choice of the site for achieving a good fit between the wind power project and the landscape identity, as perceived by the community that holds a commitment to the landscape of the site.

• Community acceptance of wind power projects. This element has received most of the attention in social acceptance studies (Wüstenhagen et al, 2007). Developers tend to misunderstand their planning problem as an attitude–behaviour ‘gap’ among local residents. However, the attitude concerns the object of wind as an energy source, whereas the behaviour is directed at the object of a wind power project, including a certain site and a particular investor. These objects are very different and, furthermore, an attitude is a bi-polar evaluation (negative or positive) whereas in behaviour the focus is on resistance, which implies that the position in favour of a proposed scheme is not questioned in the first place. As wind power is a contested realm, the legitimacy of national policy is problematic as well, in particular when hierarchical power is overtly used to site turbines. In addition to landscape concerns, community acceptance may also suffer in response to dissatisfaction with the planning and decision-making processes (Wolsink, 2007), in particular, on how public consultation is organized (Aitken et al, 2008). All studies of the underlying reasons for opposition show that the objections are very heterogeneous (Ellis et al, 2007; Jones and Eiser, 2009).

• Participation in investments or ownership. Related to the community acceptance of wind power projects is the question of whether institutional settings allow direct involvement in locally organized or publicly owned wind power. In fact, wind power might become an essential part of community energy provision (Walker and Devine-Wright, 2008). This is important, as it is the level where decisions about investments and siting of concrete wind power schemes are taken, and the community may be involved as shareholder and as stakeholder. ‘Ownership’ should not even necessarily be legal ownership, as the way in which the community is involved in the project might create identification with the wind farm ('sense of ownership’; Warren and McFadyen, 2010).

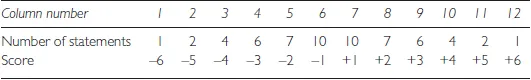

Table 6.2 Number of statements in each rank of the Q sort

In the second step, the 56 representatives (see Table 6.1) sorted the Q sample statements on a board with 60 boxes. The number of columns from left to right was 12, and the numbers per column allowed them to sort the statements in a forced ‘normal’ distribution only (Table 6.2).

The statements in Table 6.3 have letters in the column alongside them, so that they can be referred to easily in the text. This table also presents the results as scores from -6 (far left, ‘Least in accordance with my opinion’) to +6 (far right: ‘Most in accordance with my opinion’). Although the respondents gave their personal opinion, they were fully aware of the fact that they were involved in interviews representing their category of actor.

The Four Discourses on Public Involvement

In the analysis the similarities in the patterns of sorting the statements were analysed, revealing four fundamentally distinct patterns that can be interpreted as sets of coherent views on all the aspects of wind power implementation. The figures presented in the next sections give the ranks of the ‘ideal respondent’ in each of the four separate discourses.

In the analysis, some statements appear to reflect a certain consensus. An example of that is ‘If good arguments exist for constructing a wind farm in one local community instead of another, then the local authorities will agree to this’. The statement ranked mainly neutral and there was no significant variance between the four perspectives. In the analysis of the results, we focus only on ‘distinguishing statements’ – those that revealed significant differences between perspectives. As we zoom in on the perspectives on public involvement we only present data concerning statements that are associated with the categories of involvement of civil society in wind schemes, as described above. However, the reader should bear in mind that all figures are related to the complete set of statements and therefore the ranking figures on each statement are not independent from the ranks for all other statements.

Community involvement and room for independent developers

The first three discourses represent support for wind power implementation, but from different perspectives. The first is a discourse of mainly independent developers. In North Rhine–Westphalia (NRW), representatives of several of these, who cannot be considered to be developers themselves, shared the views of these independent developers: the NRW Environmental Ministry, the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety. In contrast, in England, only one actor represented this perspective, a civilians’ cooperative (Baywind). This discourse is particularly strong in the successful case of NRW, and its main characteristic is that it entails the view that support programmes should not focus on industry but on those who develop and invest in the projects. It is ...