eBook - ePub

The Challenge of Rural Electrification

Strategies for Developing Countries

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Douglas Barnes and his team of development experts provide an essential guide that can help improve the quality of life to the estimated 1.6 billion rural people in the world who are without electricity. The difficulties in bringing electricity to rural areas are formidable: Low population densities result in high capital and operating costs. Consumers are often poor, and their electricity consumption is low. Politicians interfere with the planning and operations of programs, insisting on favored constituents. Yet, as Barnes and his contributors demonstrate, many countries have overcome these obstacles. The Challenge of Rural Electrification provides lessons from successful programs in Bangladesh, Chile, China, Costa Rica, Mexico, the Philippines, Thailand, and Tunisia, as well as Ireland and the United States. These insights are presented in a format that should be accessible to a broad range of policymakers, development professionals, and community advocates. Barnes and his contributors do not provide a single formula for bringing electricity to rural areas. They do not recommend a specific set of institutional arrangements for the participation of public sector companies, cooperatives, and private firms. They argue instead that successful programs follow a flexible, but still well-defined set of principles: a financially viable plan that clearly accounts for any subsidies; a cooperative relationship between electricity providers and local communities; and an operational separation from day-to-day government and politics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Challenge of Rural Electrification by Douglas F. Barnes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Environmental Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Challenge of Rural Electrification

MORE THAN 1.6 BILLION PEOPLE in the world are without electricity. Most of these people are in rural areas of the developing world, where the pace of electrification remains painfully slow. Why is this so? Providing electricity to remote, rural people is often easier said than done. Well-publicized problems plaguing some programs have led to wariness about rural electrification among energy policymakers. Some highly subsidized programs, for example, have drained the resources of many state power companies, with highly damaging effects on their overall performance and quality of service. The result is widespread brown-outs and blackouts for their existing customers and a reluctance of the power companies to reach out and provide electricity service to the poor.

Rural electrification programs can undoubtedly face major obstacles (World Bank 1975, 1996). Low population densities in rural areas result in high capital and operating costs for electricity companies (Denton 1979; Fluitman 1983). Consumers are often poor and their electricity consumption low. Politicians interfere with the orderly planning and running of programs, insisting on favored constituents being connected first and preventing the disconnection of people not paying their bills. Local communities and individual farmers may cause difficulties over rights of way for the construction and maintenance of electricity lines.

Yet despite these problems, many countries have been quietly and successfully providing electricity to their rural populations. In Thailand, well over 90% of rural people have a supply. In Costa Rica, cooperatives and the government electricity utility provide electricity to more than 95% of the rural population. Again, in Tunisia, more than 95% of rural households already have a supply. Thus, there are many good examples of successful programs to counterbalance those that have experienced problems. This book focuses on the characteristics of successful rural electrification programs by examining the accomplishments and difficulties that have been overcome.

Rural Areas Still Lag Far Behind in Access to Electricity

Worldwide energy availability issues are under increasing scrutiny, and access to electricity services is a special concern. One reason for this scrutiny is the commitment of international development agencies to promote the Millennium Development Goals for the purpose of halving poverty by the year 2015 (United Nations 2003, Sachs 2005). Neither energy nor electricity is stated as a goal under the Millennium Development Goals, but electricity actually provides the foundations for most of them (Modi et al. 2006). Without access to modern energy services, it is generally agreed that the achievement of these goals would be difficult, if not impossible.

The growth in the number of people who have gained access to electricity over the past few decades has been quite remarkable. Today more than 1 billion more people have electricity compared to 25 years ago. But as impressive as this accomplishment is, population growth over the period has meant that big gaps in access to electricity remain. About 1.6 billion people—around a quarter of the world’s population—lack access to electricity (International Energy Agency 2002). Moreover, under today’s energy policies and investment trends in energy infrastructure, projections show that as many as 1.4 billion people will still lack access to electricity in 2030. In sub-Saharan Africa only 8% of the rural population has access to electricity, compared with 52% of the urban population. A similar disparity exists in South Asia, where only a little more than 30% of the rural population has access, compared with approximately 70% of the urban population. Indeed, four out of five people without access to electricity live in rural areas of the developing world, mainly in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

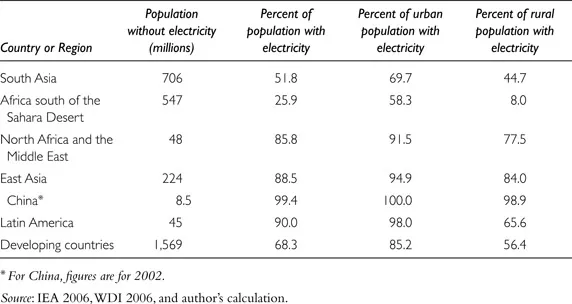

Although higher income and mainly urban households now have access to modern energy, the world’s poorest households do not (Table 1-1). With the exception of towns and cities in Africa, most urban areas in developing countries now provide electricity to their residents, although the reliability of this supply is sometimes intermittent. Thus, the problems of electricity access are now far greater in rural than in urban areas. Although urban population growth rates will continue to exceed those in rural areas, this actually means that the rural populations must become more productive and efficient at satisfying ever-increasing demands for food and other farm products.

In many African and South Asian countries, the rate of the number of people gaining access to electricity is even lower than rural population growth. In Africa, 9 out of 10 rural people do not have access to electricity or appliances. In South Asia, which has a large number of poor people, more than 800 million people do not have electricity. These dramatic figures have recently become a central issue in the debates over how to achieve improvement in education, reduction of diseases, and overall quality of life for rural people in developing countries.

The conclusion is that even though progress has been made, there still is a long way to go to raise the world’s poorest populations above the poverty line. Without access to modern energy services—including electricity—it would be virtually impossible to meet the challenge of achieving the Millennium Development Goals or more generally to reduce poverty in the developing world. Having said this, there has been some controversy over the effect of rural electrification on development in the past (Barnes 1988), and it is still true that electricity is a necessary but not sufficient condition for development. Thus, the next section deals with the role of electricity in promoting both social and economic development.

Table 1-1. Electricity Access in Developing Countries, 2005

Why Worry about Rural Electrification? A Review of Important Issues

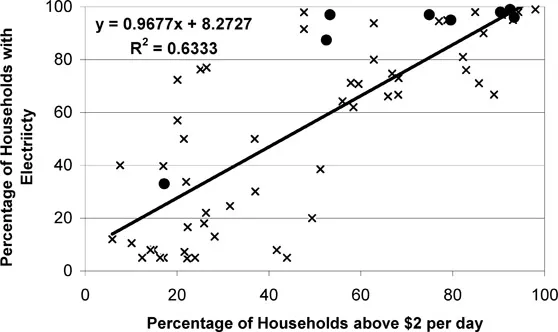

Countries are often faced with a dilemma concerning the provision of electricity. Over the long term, the benefits of providing electricity to poor rural households can be quite high, as evidenced by the well known positive relationship between electricity consumption and gross domestic product. This correlation is mirrored by the relationship between a country’s rate of electrification and the percent of households that are above the poverty line of two dollars per day (Figure 1-1). This figure illustrates that the rate of electrification is related to the percentage of a country’s population that is above the poverty line. Their rates of electrification are higher than what would be expected given their level of development, but despite this relationship, the initial cost of developing the infrastructure is high and unaffordable for poor people. The benefits must be evaluated and compared to the costs involved in providing electric service. Building extensive central grid distribution systems with miles of medium- and low-voltage lines is expensive to light a few light bulbs in the rural areas that have low densities of consumers.1

The social and economic benefits of rural electrification have been researched over the past 30 years. One notable review was conducted in the early 1980s covering several countries (USAID 1981; Butler et al. 1980; Goddard et al. 1981; Madigan et al. 1976; Mandel et al. 1980). Intuitively, one can easily understand that in households with electricity, people are better able to undertake activities that require higher levels of lighting, such as reading and studying (Barnes et al. 2003; Samanta and Sundaram 1983). They can also listen to the radio or watch television, and attend to more household chores (World Bank 2004a, b). In contrast, the kerosene lantern or candles in the household without electricity emit a dull light inadequate for reading or close work (Nieuwenhout et al. 1998; Van der Plas and de Graaff 1988). In such households with no electricity, the family may retire early after a fairly unproductive evening.

Figure 1-1. The Relationship between the Percentage of Electrification and the Poverty Rate for Developing Countries

Note: The eight developing countries in this report are indicated by solid circles. Data for rural electrification rates are for 2002, and for the % households above poverty, they range from 2000 to 2004.

Source: World Bank 2002. Development Data Group, World Development Indicators database. Tables prepared on electrification rate for business renewal strategy. Energy and Water Department, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Such accounts may seem to overstate the actual value of rural electrification, but they are typical of the expected benefits for rural areas anticipated by both politicians and those still living in rural communities without electricity. In this section, we review the evidence of the social and economic effects of rural electrification, but not the benefits versus the costs, as this is a completely different area of research (for a review, see Webb and Pearce 1985; Barnes and Halpern 2000; World Bank 2002b). In addition, there is discussion of equity issues and subsidies for rural electrification.

Importance of Social Effect and Household Benefits

The arguments for rural electrification often have centered on the transformative effect that it can have for rural households. At the micro level, the effect of rural electrification on a household can be substantial. At the macro level, the arguments for rural electrification have revolved around the productive work that can be done in rural areas with electricity.2

In rural households that adopt electricity, lighting is the first choice by households as they begin to use electricity. Virtually 100% of households with electricity use it for lighting, as electricity allows activities to continue through the evenings. Cooking is not changed significantly in most households with electricity, except in Latin America, where electricity is used for cooking in some urban areas. In general, rural households prefer the traditional wood, coal, and charcoal stoves to the more expensive electric stoves or even heating plates or coils. However, there is some emerging evidence that in households with electricity, women are spending less time in fuel collection and meal preparation, even though they do not change their cooking fuels (World Bank 2002a, 2004a). The apparent reason is that with lighting in the evening, women can prepare the main meal just before it is eaten rather than preparing some dishes during the day and then reheating them at night.

Women and children are prime beneficiaries of rural electrification. Lights and appliances had a significant effect on household work in the early stages of rural electrification programs in the United States, as appliance use reduces the drudgery of household chores. A study in India found that electric appliances helped decrease the amount of toil and thus increased the time available for family and leisure activities (World Bank 2004a). At a minimum, all households used electricity for lighting. The other major uses were space cooling (fans) and watching television. This report also established that in general women from homes with electricity were better able to balance paid work, household chores, and leisure than women from homes without electricity. Similarly in Bangladesh (Barkat et al. 2002), women in households with electricity spent less time on household chores. Other studies have found that lighting alone made a dramatic difference in one’s ability to do household chores at night and to read for education and leisure (Lay and Hood 1976; Khandker 1996; Gordon 1997; Filmer and Pritchett 1998; Kulkarni and Barnes 2004). However, the socioeconomic background of the household often determined the trade-offs they made with their time and the extent to which they could enjoy the advantages of electrification.

To conclude, an overriding impression from some of the recent reviews is that rural electrification has a significant social effect. For instance, the positive benefits include increased appliance use and more reading—especially for children. The findings of the effect of electricity on migration are somewhat mixed (Herrin 1979), with no conclusive evidence. Education and electrification definitely appear to be mutually reinforcing programs (Saunders et al. 1978; Velez et al. 1983; Khandker et al. 1994; World Bank 1999; Kulkarni and Barnes 2004; Arcia 2000). In this section, the social benefits of electricity have been reviewed without reference to the division of the benefits between social classes. In other words, the benefits of rural electrification may well be distributed unevenly among the rural population. The next section examines the equity of the effect of rural electrification.

Importance of the Economic Impact

Due to the importance of economics for rural life, a brief review of the economic effect of rural electrification is in order.3 This section concentrates on the effect of electricity on agriculture and on the growth of rural businesses. However, to a great extent the economic effect of electricity depends on government policies directed toward either household or productive uses. In some countries and among some donor agencies, the overemphasis on the economic benefits of rural electrification has meant a lack of proper perspective. This emphasis does not mean to deny the importance of electricity for economic development, but policies supporting both social and economic effects seem to lead to favorable program results.

For instance, the rural electrification policy in India since the early 1960s has focused on the promotion of electric pump sets, which has had a large effect on agricultural productivity (Das 1990; Bose 1994; Barnes 1988). This effect is in part due to the fact that India has in place an aggressive agricultural development program, including the dissemination of hybrid seeds, fertilizers, and other agricultural inputs, along with a policy to subsidize electricity for water pumping. Credit programs also have helped agricultural development in India, whereas in some other countries there are no similar programs to complement rural electrification.4

India’s effort to improve rural development through electrification has been relatively successful, but it is not unique (Barnes et al. 2003). For instance, the growth of electric pump sets in Bangladesh is much lower than those experienced in India, but it has been higher than was expected at the beginning of the program (Barkat et al. 2002). However, no similar effect has been measured in other countries. For instance, one survey in a relatively rich rice-growing region in Indonesia found that the rate of growth of pump sets was low because most irrigation was accomplished through gravity-fed sources (Brodman 1982; U.S. Census Bureau 1980). This finding is similar to those in the rice growing regions in India (World Bank 2002a; Barnes et al. 2003). Also, the price of diesel fuel in Indonesia is heavily subsidized, making it less attractive for farmers with pumps to switch to electricity. Thus, the productive effect of rural electrification can be substantial, but the effect depends on factors such as government policy and complementary programs.

Businesses in rural areas of developing countries include home businesses, small commercial shops, grain mills, sawmills, coffee and tea processing, as well as brick kilns (for a review, see Cabraal and Barnes 2006). The effect of rural electrification on small businesses is determined by the nature of the local community, the complementary programs, and the ability of rural entrepreneurs. Although electricity is an important and often essential input that helps in the development of small rural industries, the other complementary conditions include access to good rural markets and adequate credit. Perhaps because these complementary conditions are not present in all rural areas, the anticipated growth of industries in rural areas provided with electricity is somewhat slow (Zomers 2001). However, areas without electricity have an even worse record of business development. For instance, in a recent study in the Philippines, small home businesses were found to be more active in areas with electricity, contributing to family incomes (World Bank 2002b). The majority of these businesses are small general stores for food and other necessities.

Finally, an overemphasis on rural productivity can divert attention away from the household benefits. As indicated earlier, there are substantial social benefits of rural electrification, which accrue mainly in the evening hours, when small businesses and commercial establishments are not operating. Thus, the same investments can serve two complementary purposes at the same time.

The conclusion is that electrification is an important condition for the development of rural businesses and that under the right circumstances, it has resulted in significant economic growth. However, it is unrealistic to expect that it will produce an explosion of industry and commerce in a short time, especially in the absence of other development programs. Concerted effort is needed to coordinate rural electrification with other relevant programs. Without such complementary programs, the full socioeconomic effect of electrification probably will not be realized, and the required substantial capital investments may not be fully exploited. Electrification projects properly coordinated with such programs or implemented under the rig...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Contributor

- 1. The Challenge of Rural Electrification

- 2. The Cooperative Experience in Costa Rica

- 3. Power and Politics in the Philippines

- 4. Rural Poverty and Electricity Challenges in Bangladesh

- 5. Public Distribution and Electricity Problem Solving in Rural Thailand

- 6. From Central Planning to Decentralized Electricity Distribution in Mexico

- 7. Electricity and Multisector Development in Rural Tunisia

- 8. Rural Electricity Subsidies and the Private Sector in Chile

- 9. National Support for Decentralized Electricity Growth in Rural China

- 10. The New Deal for Electricity in the United States, 1930–1950

- 11. Electricity for Social Development in Ireland

- 12. Meeting the Challenge of Rural Electrification

- References

- Index