![]()

Part I

On Dexterity and Its Development

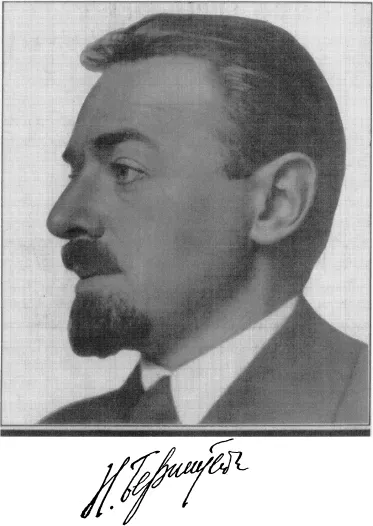

N. A. Bernstein

![]()

Introduction

This book was written in response to a suggestion by the Administration of the Central Research Institute of Physical Culture. This suggestion contained two objectives: first, to present as strict and precise a definition and analysis of the complex psychophysical capacity of dexterity as possible; second, to provide a popular overview of the contemporary understanding of the nature of movement coordination, motor skill, exercise, and so forth, which are of very high practical importance for both professionals in the area of physical education and for all the numerous participants of the physical-culture drive in our country, an overview that should encourage genuine culture in all connotations of this word. Thus, the book was conceived as popular-scientific.

The need for popular-scientific literature is very strong in our country. It would be basically wrong to dismiss this kind of literature on the grounds that the Soviet Union does not need “semieducated” citizens and that its citizens should have an undisputed right and means to master special literature without the condescension and arrogance that are, as some claim, inevitably present in popular-science literature. This view is totally wrong.

The time when a scientist could be equally well oriented in all areas of the natural sciences passed, irreversibly, long ago. Even 200 years ago, it required the omnipotent genius of Lomonosov for such universality. In essence, he was the last representative of universal natural scientists. During the two centuries that separate us from Lomonosov, the volume and content of natural science have grown so immensely that scientists of our day spend all of their lives mastering the material of their major, narrow areas of specialization. Very few of them find enough time to follow the heavy flow of the scientific literature in order not to lag behind even in their own field. They are rarely able to find time to mull over other areas of their own science and even less time for other areas of natural science in general.

Bernstein in the mid-1940s.

This overflowing stream of new information in all the branches of natural science and, directly related to its growth, the increasing differentiation of scientific and scientific-practical professions, create an increasing danger of turning their representatives into narrow specialists lacking any general horizon, blind to anything except the narrow path that they have chosen in life. This narrowing of the general perspective is dangerous not only because it deprives people of the irresistible beauty of wide general education but also because it teaches them not to see the forest behind the trees even in their narrow area; it emasculates creative thinking, impoverishes their work with respect to fresh ideas and wide perspectives. Jonathan Swift, also about 200 years ago, predicted the emergence of such “gelehrters” with blinkers on their eyes, blind, confused cranks; Swift sharply ridiculed them in his description of the Academy of Sciences on the Island of Lagado.

The role of popular-scientific literature is to overcome this danger. Let it be guarded by all the muses from condescending arrogance toward the reader, from the Horacius’ Odi profánum vulgus et arceo! (“Hate the dark mob and drive it off!”). The popular-scientific author must approach the reader, not as an ignoramus, not as a vulgar mob, but as a colleague who needs to become acquainted with the basic facts and current conditions of an adjacent area of science, an acquaintance that the reader would never be able to achieve by studying the same problems in the mountains of original papers and special literature. The popular-scientific author strives to provide the reader with a wide perspective, one that is necessary for both theoretical and practical creativity in any area, and tries not to descend to some imaginary, unrespected lay reader but to elevate the colleague-reader from a different area to a bird’s flight from where he is able to see the whole world.

A contemporary professional, whether a theoretician or a practician, should know everything about his own basic area and basic things about everything.

The area of theoretical linguistics related to popular-scientific writing is absolutely undeveloped. It is ruled by chaos, unclearness, and groping empiricism. If one wants to make a contribution to this kind of literature, being as serious and responsible as it deserves, the author must first of all realize how to start. As far as I am able to discern, there are three different styles in the contemporary popular-scientific literature.

Typical examples of one of them are widely available and well-known books including Prosvyastcheniye (“Enlightment”): The World by A. Meier, The History of Earth by I. Neymark, The Human by L. Ranke. Books of this kind are not much different from any textbooks or special literature, aside from taking into account the level of the targeted reader. Such authors do not try to entice the reader or to excite the reader’s curiosity; any enticement and curiosity stem directly from the inherent interest of the theme and the subject themselves. Their style is dry, businesslike, based on a strict plan that is mostly defined by the dogmatics, not the didactics, of the subject.

The second style of popular-scientific literature may be called Flammarion. Widely known books by C. Flammarion on astronomy and cosmography are characterized mostly by two basic features. First, they continuously flirt with the reader, particularly with the female reader, whom the author, according to the ideas of the bourgeois society of the 19th century, depicts as an extremely prim, impatient, and ignorant person but for whom he does not spare any amount of gallantry. Second, the text is diluted. Undoubtedly, simplicity of discourse and percentage of dilution are not the same things; we are aware of many examples of very specialized and hard-to-understand scientific works that nonetheless contain about 90% of a useless, liquid solvent. From my view, such swelling of a book does not help any more than flirting with the readers of either gender.

The third style is the most recent one and most brightly illustrated by the books by P. De Kruif dedicated to the history of great inventions in medicine and biology. De Kruifs first and most talented book, Microbe Hunters is well known and very popular in our country. As far as I know, De Kruif was the first to introduce into popular-scientific literature a brave, impressionistic style, enriched with all the contemporary achievements of general stylistics. His text is rich with images, bright comparisons, and humor, and he sometimes ascends to the passionate enthusiasm of a zealot for science and advocate for the martyrs. He is helped by the historical aspect that is present in most of his books, whether it is history of a great invention with all its intricate complications or history of the life of a great scientist. In both cases, the narration is filled with dynamic and developing intrigue. The reader holds his breath to find out what will happen next and is eager to peek at the last page, as some young ladies do when reading a breathtaking novel. The title of the first book by De Kruif, Microbe Hunters by itself introduces the reader to his style and manner. De Kruif turns the history of the scientific struggle into a fascinating, adventurous novel without devaluing the described events and their significance.

The style of De Kruif has begun to find followers in the Soviet Union. For example, the bright essays of Tatyana Tess, which are dedicated to the most prominent contemporary Soviet scientists and which sometimes appear in the major newspapers, are undoubtedly influenced by the style of De Kruif. Also, the style of the essays of Larisa Reisner, who died an untimely death, have much in common with that of De Kruif.

I decided to use the style of De Kruif because of a number of its attractive features. The endeavor, however, turned out more complex because of the lack of plot dynamics. My problem was to apply this style to describing a theory, an area of science, with its somewhat inevitable lack of dynamics. The third essay (“On the Development of Movements”) was the easiest one, exactly because of its historical nature, which gave me a chance to dramatize the fascinating canvas of movement evolution in the animal world up to human beings.

In the other essays, I decided to use the whole available spectrum of means developed and ordained by the theory of belles lettres, every artistic method that has been sanctioned by it. I am determined not to be afraid of any Russian word that is able to express the required ideas most accurately and vividly, even if that word is not included in the official (scientific and administrative) language. Furthermore, I extensively use different kinds of comparisons, from fleeting metaphors, lost somewhere inside subordinate clauses, to extensive parallels that occupy a full page.

My desire to make the text as lively as possible led to the inclusion of a number of narrative episodes, from fables and myths to realistic essays predominantly related to impressions from the Great Patriotic War (World War II). Finally, as for the illustrative material, I enjoy the full support of the publisher and introduced numerous drawings into the text. The book contains drawings whose content closely accompanies the material and also a number of scientific illustrations indirectly supporting the discourse (these are mostly drawings from areas of anatomy, zoology, and paleontology and photographs of the highest athletic achievements). I decided not to be afraid of including an element of humor in some cartoons, genially making fun of clumsiness and awkwardness or suggesting unrealistic examples of dexterity and skillfulness.

All these attempts in the area of popular-scientific literature are, perhaps, just one big mistake. Undoubtedly, however, there is a chance that at least a small grain of what has been found was found correctly. Indeed, only those who never search never err, and, on the other hand, not one of the (re)searchers ever expected to find something worthwhile at the first attempt.

Let me rely on harsh, albeit friendly, critique and on the reader’s experience in pronouncing the final judgment.

![]()

Essay 1

What Is Dexterity?

RECONNAISSANCE AND BATTLES OF SCIENCE

Physiology long ago passed beyond being merely “the frog science.” The subject grew both in size and in level of development. It addressed doves and chickens, then moved to cats and dogs. Later, a respectful place in the laboratories was taken by monkeys and apes. The persisting requirements of practice moved physiology closer and closer to human beings.

There was a time when the human was considered a unique being, a semigod. Any research into the human bodily structure and function was considered sacrilegious. Spontaneous scientific materialism took its position in science only about 300 years ago; at that time, the first frog was dissected. However, in current times, the depth of the abyss between humans and all other living beings has become apparent. Here, the subject was not human supernatural origin or immortal soul. The abyss was revealed by the inevitable, persisting requirements of everyday practice. Physiology of labor and physiology of physical exercise and sport emerged. What kind of labor can be studied in cats? What is common between the frog and the track-and-field athlete?

Thus, genuine human physiology and genuine human activity has developed and expanded. Scientists attacked one bastion after another, delving deeper and deeper into the mysteries of functions of the human body.

Development of each natural science, including physiology, might well be compared to a persistent victorious offense. The adversary—the unknown—is strong and is far from being defeated. Each inch of land has been captured only after fierce battles. The offense does not go smoothly. Sometimes, it is stopped for quite a while, as the opponents entrench and try to gather new forces. Sometimes, a seemingly captured area is taken back by the adversary—the unknown. This regression happens when a promising scientific theory is proved wrong, because its fundamental facts were misunderstood or misinterpreted. Nevertheless, the regiment of science knows only temporary upsets and misfortunes. Scientific offense is like ocean high tides: Each wave is only half a meter higher than the previous one, but wave after wave and minute after minute, they push the tide higher and higher. The difference from high tides is that the scientific offense does not end.

There are many common features between the development of science and the battlefield. There is a slow, methodical movement of the whole front when each step is taken once and forever. There are brave assaults, clever breakthroughs, which quickly penetrate deep into the area that had offered the most resistance for years. Such breakthroughs of genius in scientific battles include the discoveries of Nikolai Lobachevsky, Louis Pasteur, Dmitri Mendeleev, and Albert Einstein. In science, as in battles, an important role is played by short reconnaissance sallies deep into the enemy’s rear. Such excursions are not attempts to capture and retain a new piece of territory. They can yield, however, important information on the deep enemy arrangements and help the main body of the army to reorganize prior to a major offensive operation by the whole front.

For a quarter of a century, I worked as a modest officer in the army of science, in the regiment of human physiology. During all these years, I took part only in the slow, systematic offensive actions of the science infantry. The suggestion that I write essays on the physiology of dexterity was the first reconnaissance assignment because this area had only a few bits of facts that were firmly established by scientific research. It seems to be the proper time to undertake such an intelligence action because life urges it. Was the choice of the officer lucky? How valuable is the collected material? These questions are not for me to answer. The intelligence report is here, in front of the reader, in form of a book. Let the reader make the decision.

PSYCHOPHYSICAL CAPACITIES

The banner of physical culture bears the names of four notions that are commonly addressed as psychophysical capacities: force, speed, endurance, and dexterity.

These four are quite unlike each other.

Force is virtually a purely physical feature of the body. It depends directly on the volume and quality of the muscles and only indirectly on other factors.

Speed is a more complex feature that combines elements of both physiology and psychology.

Endurance is even more comple...