![]()

Part I

Status and Global Trends

![]()

1

Current Status of the Biofuel

Industry and Markets

A GLOBAL OVERVIEW

The liquid biofuels most widely used for transport today are ethanol and biodiesel. Ethanol is currently produced from sugar or starch crops, while biodiesel is produced from vegetable oils or animal fats. The growth in the use of biofuels has been facilitated by their ability to be used as blends with conventional fuels in existing vehicles, where ethanol is blended with gasoline and biodiesel is blended with conventional diesel fuel.

Ethanol currently accounts for 86 per cent of total biofuel production.1 About one quarter of world ethanol production goes into alcoholic beverages or is used for industrial purposes (as a solvent, disinfectant or chemical feedstock); the rest becomes fuel for motor vehicles.2 Most of the world's biodiesel, meanwhile, is used for transportation fuel, though some is used for home heating.

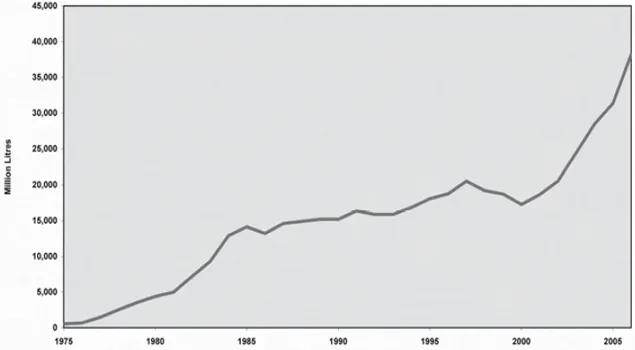

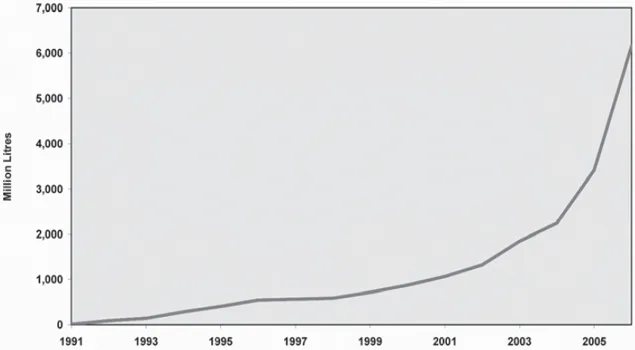

Global fuel ethanol production more than doubled between 2001 and 2006, while production of biodiesel, starting from a much smaller base, expanded nearly sixfold (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2).3 In contrast, the oil market increased by only 10 per cent over this period (in absolute terms, however, world petroleum production increased by some 80 million litres a year from 2001 to 2006, compared to some 5 million litres annually for biofuels).4 In 2006, biofuels comprised about 0.9 per cent of the world's liquid fuel supply by volume, and about 0.6 per cent by transport distance travelled. Yet, as a percentage of the increase in supply of liquid fuels worldwide from 2005 to 2006, the surge in production of the two biofuels accounted for 17 per cent by volume and 13 per cent by transport distance travelled.5

HISTORY OF BIOFUEL PRODUCTION PROGRAMMES

Biofuels have been used in automobiles since the early days of motorized transport. American inventor Samuel Morey used ethanol and turpentine in the first internal combustion engines as early as the 1820s. Later that century, Nicholas Otto ran his first spark-ignition engines on ethanol, and Rudolph Diesel used peanut oil in his prototype compression-ignition engines. Henry Ford's Model T could even be calibrated to run on a range of ethanol–gasoline blends. However, just as automobiles were becoming popular at the beginning of the 1900s, the fuel market was flooded with cheap petroleum fuels.6

Figure 1.1 World fuel ethanol production, 1975–2006

Source: F. O. Licht

Figure 1.2 World biodiesel production, 1991–2006

Source: F. O. Licht

Biofuels represented only a small proportion of total fuel during the early 20th century. They were supported by policies in several European countries, especially France and Germany, where at times they neared 5 per cent of the fuel supply. In tropical areas with irregular supplies of petroleum and in enclosed settings such as mines, biofuels were often the favoured fuel; during World Wars I and II, ethanol was also used to supplement petroleum in Europe, the US and Brazil. However, military demobilization in the post-war period and the development of new oil fields in the 1940s brought a glut of cheap oil that virtually eliminated biofuels from the world fuel market.7

The oil crises of the 1970s prompted countries to again seek alternatives to imported oil. Brazil, which had maintained a small fuel ethanol industry since the 1930s, expedited a national ethanol programme called Proálcool with an eye to alleviating its great national debt and expanding its agricultural industry. Especially after the second oil crisis of 1979, when oil prices reach their historic zenith, the Brazilian government prioritized ethanol production, supporting expanded sugar cane acreage, new ethanol distilleries and ethanol-only cars. By the mid 1980s, ethanol was displacing almost 60 per cent of the country's gasoline.8

Also motivated by the high and volatile oil prices of the 1970s, the US launched its own fuel ethanol programme at the end of the decade, using corn to produce a proportionally small but increasing amount of ethanol. The Brazilian and US ethanol industries still produce the vast majority of the world's fuel ethanol – almost 90 per cent in 2005.9

The oil crises prompted other countries to promote biofuels as well, although these efforts were less successful. In China, the government encouraged peasants to cultivate oil plants that would provide insurance against disruptions in the supply of diesel fuels; but it abandoned these efforts after the price of oil fell in the mid 1980s.10 In 1978, the Kenyan government initiated a programme to distil ethanol from sugar cane, mixing it in a 10 per cent blend with gasoline; but this programme faltered due to drought, poor infrastructure and inconsistent policies.11 Zimbabwe and Malawi initiated larger programmes in 1980 and 1982, respectively; but only Malawi has consistently produced fuel ethanol since then.12

In Europe, a trade dispute triggered a rise in biodiesel production, starting in 1992. The European Union (EU) agreed to prevent gluts in the international oilseeds market by confining production to just under 5 million hectares. European governments helped to create a new market for farmers on the remaining ‘set-aside’ land, primarily by reducing the taxes on biodiesel – a policy that has led to a rapid increase in European biodiesel production, particularly in Germany.13

More recently, environmental standards have become important drivers for biofuel markets. In the US, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began requiring cities with high ozone levels to blend gasoline with fuel oxygenates, including ethanol. When state governments learned in the late 1990s and early 2000s that the most common oxygenate, methyl tertiary-butyl ether (MTBE), was a possible carcinogen that was seeping into groundwater, 20 states passed laws to phase it out, creating a surge in demand for US ethanol in the early 2000s.14

In Brazil, the auto industry's 2003 introduction of so-called flexible-fuel vehicles (FFVs), which can run on any combination of gasoline or ethanol, has given drivers the freedom to choose whichever of the fuels is cheaper. Consumer demand for these vehicles has surged, and by early 2006, more than 75 per cent of new cars sold in the country were FFVs.15 Combined with high petroleum prices, these cars have led to a dramatic increase in Brazilian ethanol production.16

CURRENT BIOFUEL PRODUCTION

The US and Brazil dominate world ethanol production, which reached a record 38.2 billion litres in 2006 (see Table 1.1).17 Close to half the world's fuel ethanol was produced in the US in 2006, nearly all of it from corn crops grown in the northern Midwest, representing 2 to 3 per cent of the country's non-diesel fuel.18 More than two fifths of the global fuel ethanol supply was produced in Brazil in 2006, where sugar cane grown mostly in its centre-south region provides roughly 40 per cent of the country's non-diesel fuel.19

The remainder of ethanol production comes primarily from the EU, where Spain, Sweden, France and Germany are the big producers, using mainly cereals and sugar beets. China uses corn, wheat and sugar cane as feedstock to produce a large amount of ethanol destined mostly for industrial use. In India, sugar cane and cassava have been used intermittently to produce fuel ethanol.20

Table 1.1 World fuel ethanol production, 2006

|

| Country or region | Production (million litres) | Share of total (percentage) |

|

| United States | 18,300 | 47.9 |

| Brazil | 15,700 | 41.1 |

| European Union | 1550 | 4.1 |

| China | 1300 | 3.4 |

| Canada | 550 | 1.4 |

| Colombia | 250 | 0.7 |

| India | 200 | 0.5 |

| Thailand | 150 | 0.4 |

| Australia | 100 | 0.3 |

| Central America | 100 | 0.3 |

| World Total | 38,200 | 100.0 |

|

Source: see endnote 17 for this chapter

In 2005, many new ethanol production facilities began operating, were under construction or were in the planning stage. For example, US ethanol production capacity increased by nearly 3 billion litres during 2005, with an additional 5.7 billion litres of new capacity under construction going into 2006.21

Biodiesel has seen similar growth, almost entirely in Europe (see Table 1.2).22 Biodiesel comprises nearly three-quarters of Europe's total biofuel production, and in 2006 the region accounted for 73 per cent of all biodiesel production worldwide, mainly from rapeseed and sunflower seeds.23 Germany accounted for 40 per cent of this production, with the US, France and Italy generating most of the rest.

The rapidly changing character of worldwide biofuel production capabilities is illustrated by recent trends in the US. US biodiesel production, mainly from soybeans, was 1.9 million litres (500,000 gallons) in 1995; by 2005, it had jumped to 284 million litres (75 million gallons); and in 2006 it tripled, to 852 million litres (224 million gallons).24 At mid-2006, US biodiesel production capacity stood close to 1.2 billion litres per year from 42 facilities, and more than 400 million litres per year of additional production capacity were under construction at 21 new plants.25, 26 Meanwhile, the EU was home to approximately 40 biodiesel plants, and this capacity was also growing rapidly, both in Germany, which has been the clear leader in world biodiesel production, and also in Austria, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Sweden.

Table 1.2 World biodiesel production, 2006