![]()

1

Setting the Scene:

Polar Cruise Tourism in the 21st Century

Michael Lück , Patrick T. Maher and Emma J. Stewart

Introduction

The polar regions have long fascinated explorers and researchers, from the early adventures of explorers, such as Shackleton, Scott and Amundsen, to modern day scientists who have access with modern military aircraft to research stations such as McMurdo Station and Scott Base in Antarctica, and Alert and Ice Station Barneo in the Arctic. Tourism to these remote and hostile environments has a much shorter history; however, the polar tourism sector has increased rapidly over the past two decades. Climate change is affecting these regions to a large extent and, in turn, has repercussions for tourism (Maher, 2008). In fact, some argue that tourism will increase in the form of ‘last chance tourism’ or ‘doom tourism’, where people rush to see places before they disappear. A particular case in point is polar bear viewing in Churchill, Manitoba, where polar bear populations are feared to rapidly decline due to the effects of climate change (Lemelin et al, in press). On the other hand, tourism to the polar regions may become easier due to a lack of ice and generally milder conditions – so much so that some of the main attractions, such as icebergs and wildlife that are dependent upon them, are not guaranteed to be seen at all times (Schwabe, 2008). This may have an adverse effect on visitor satisfaction (Maher, in press) and demand (Stewart et al, 2007). In order to raise awareness, and better understand the climatic processes in the polar regions, the Fourth International Polar Year (IPY) was proclaimed by the International Council for Science (ICSU) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) as a large scientific programme focused on the Arctic and the Antarctic from March 2007 to March 2009 (ICSU and WMO, 2009). As we have commented elsewhere (Maher et al, in press; Maher and Stewart, 2007), unfortunately there was an overall lack of tourism-related research projects under the auspices of the IPY; but as the collection of chapters in this book indicates, critical issues about polar tourism, and polar cruise tourism in particular, are becoming important and active areas of research.

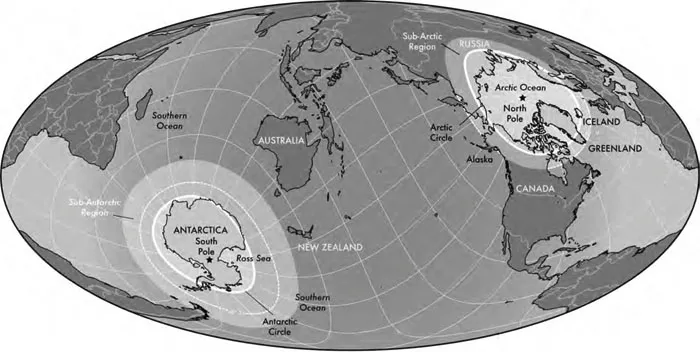

Polar tourism is defined as ‘tourism that occurs in the polar regions’ (Maher et al, in press, p1); however, defining the polar regions is more difficult and ambiguous. Delineating Antarctica is relatively easy, as Figure 1.1 shows, with land and sea south of 60°S considered Antarctica, as outlined by the Antarctic Treaty System. Subsequently, the sub-Antarctic is land and sea between 60°S and 45°S, including all the islands of the Southern Ocean, and the tip of South America (Maher et al, in press). In contrast, the Arctic and sub-Arctic are much more difficult to define. This can be done by either political boundaries (e.g. the three northern Canadian territories at 60°N, or the Arctic Circle) or by biophysical boundaries, such as the tree line or the July 10°S isotherm (Maher et al, in press). Maher (2007) suggests that because large parts of the Arctic are dependent on the marine environment, a marine delineation of the Arctic would be useful and appropriate. In addition, there are different terms used interchangeably by different authorities, such as the ‘High North’, ‘North’, Circumpolar North’ and the ‘Arctic’. The Arctic Human Development Report defines the Arctic as encompassing:

… all of Alaska, Canada north of 60°N together with northern Québec [Nunavik] and Labrador [Nunatsiavut], all of Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and Iceland and the northernmost counries of Norway, Sweden and Finland … [in Russia], the Murmansk Oblast, the Nenets, Yamalo-Nenets, Taimyr, and Chukotka autonomous okrugs, Vorkuta City in the Komi Republic, Norilsk and Igsrka in Krasnoyarsky Kray, and those parts of the Sakha Republic whose boundaries lie closest to the Arctic Circle. (Stefansson Arctic Institute, 2004, pp17–18)

Figure 1.1 The polar regions

Source: Shawn Mueller, University of Calgary, Canada

The cruise industry and the polar regions

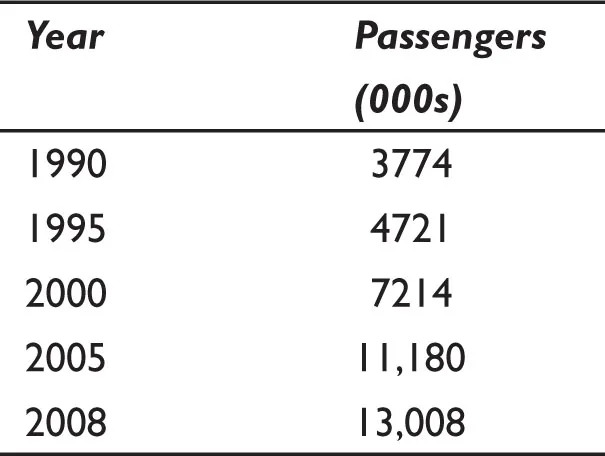

The cruise industry has seen phenomenal growth rates over the past few decades. Some sources contend that it is the fastest growing sector of the tourism industry (Dowling, 2006; Lück, 2007; CLIA, 2009), with growth rates of up to 1800 per cent since 1970 (CLIA, 2006). Table 1.1 illustrates the growth of the industry for the 25 member cruise lines of the Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA), which account for approximately two-thirds of the total market. Thus, it is estimated that, overall, close to 20 million people took a cruise in 2009 (R. Klein, pers comm). Despite the fact that the cruise industry accounts for only 0.6 per cent of all hotel beds offered worldwide (Dowling, 2006), it is a significant player in the tourism industry.

Table 1.1 Passenger numbers on CLIA member cruise lines

Source: CLIA (2009)

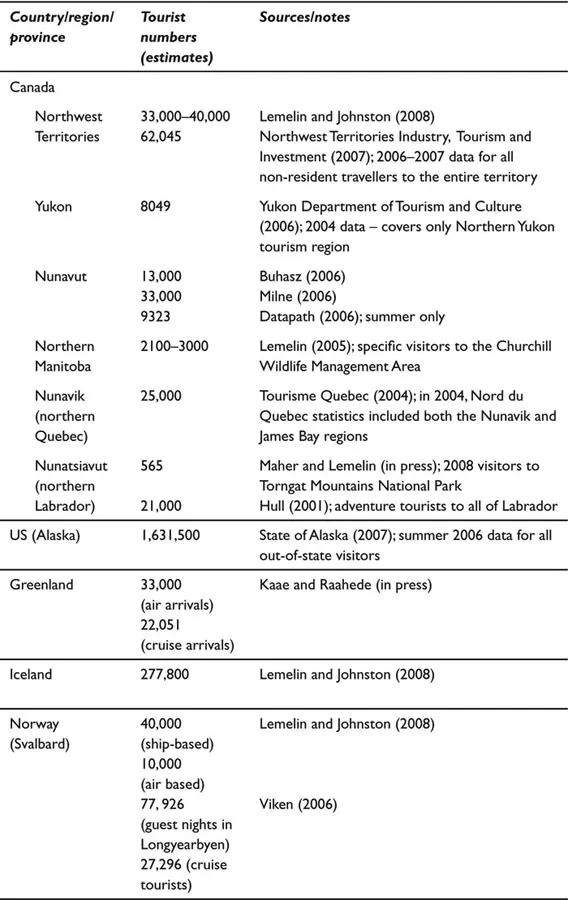

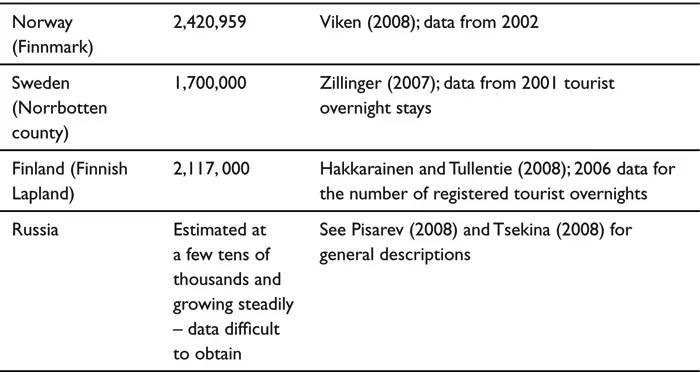

The growing trend in the cruise industry is equally reflected in a rapidly growing cruise activity in the polar regions. The majority of tourists to these regions are cruise ship-based, with Antarctica’s tourism almost being entirely ship-based. CLIA member lines saw an increase in capacity from approximately 4.2 million bed-days in 2000, to just under seven million bed-days in 2009 for Alaska-bound cruises. For Antarctica cruises, the number of bed-days increased from 49,000 in the year 2000 to 217,000 in 2009 (CLIA, 2009). Antarctica also sees a small number of small private yachts (estimated at about 1000 people), and a number of passenger over-flights (not landing on the continent) from Australia and, to a lesser extent, from Chile (Higham, 2008). Lemelin and Johnston (2008) contend that Arctic tourism is mostly based on wildlife (e.g. polar bears and whales) and landscape (e.g. fjords, glaciers and icebergs) as attractions. Due to the fact that the Arctic is more difficult to define and that not all tourists are ship-based, it is much more difficult to obtain reliable data about tourism activities in the Arctic. Data compiled from various sources are shown in Table 1.2. Numbers for Sweden, Finland and Norway (excluding Svalbard), and Alaska are assumed to be quite large; but statistics separating Arctic/sub-Arctic tourism from general tourism in these countries/states do not exist. Similarly, there is modest cruise ship activity in Russia, but data is not available (Lemelin and Johnston, 2008).

Table 1.2 Estimated tourist numbers in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions

Given the steadily increasing demand for polar tourism, tour operators are reacting accordingly. Skagway in Alaska, for example, experienced growth to an extent that this small town now receives daily cruise ship visits from mid May to mid September, with four to five ships almost daily during the summer months of July and August (Cruise Line Agencies of Alaska, 2009). On a busy day in July, this means that up to 10,000 passengers would disembark in a town with a population of approximately 800. Similarly, in the Canadian Arctic, the number of cruise ships doubled to 22 cruises during 2006 (Stewart et al, 2007) and by 2008 six vessels carried approximately 2400 passengers on 26 separate cruises representing the busiest ever cruise season in Nunavut (Stewart et al, 2010). More dramatically, Antarctica has seen large increases in cruise ship activity, and especially in the size of ships. During the 2008 to 2009 season, 37,858 passengers (plus 24,579 staff and crew) visited Antarctica on a number of ships (IAATO, 2009). While the ratio of ship-based passengers decreased slightly due to the success of air/ship operations, the vast majority (96 per cent during the 2004/2005 season) of tourists to Antarctica are still ship-based, with growth rates in excess of 400 per cent between the 1992/1993 and the 2005/2006 seasons (Bertram, 2007; Higham, 2008).

As the sinking of the Explorer in November 2007 off the Antarctic Peninsula illustrates, there are concerns associated with the enormous growth rates of polar tourism (Stewart and Draper, 2008). Key stakeholders, including national programme managers, tour operators and tourists themselves have to adapt to situations previously unheard of. In 2008, for example, a passenger who was booked on a cruise via the Northwest Passage successfully sued the tour operator for a shortcoming of his trip: the brochure of the operator promised ‘meter-thick pack ice’. During the journey in July 2007, there was no ‘meter-thick pack ice’ to be seen (attributed to the effects of climate change), and the court agreed that this was a shortcoming of the journey and a broken promise of the tour operator, despite the tour operator’s brochure advising that schedules may have to be changed due to extreme weather (Schwabe, 2008). In contrast to not having enough ice, in November 2009, the Russian icebreaker Kapitan Khlebnikov was stuck in ice around Antarctica with 101 passengers, 23 staff and 60 crew on board (Associated Press, 2009; Shaw, 2009). The return to Ushuaia, Argentina, was delayed by eight days, and in order to pass the time in the ice, the operator organized tours to spend time at the Snow Hill Island Emperor Penguin Rookery (Shaw, 2009). While there was no obvious risk for an icebreaker like the Kapitan Khlebnikov in such a situation, there is concern about the increasing number of regular large cruise liners visiting the polar regions, which are not ice-strengthened. A potential rupture of the hull, or even a sinking, could result in the leaking of oil and other hazardous liquids, which would be a disaster for fragile polar environments (O’Grady, 2006). In addition, a search and rescue mission to such remote areas, and in adverse weather conditions, is very difficult at best. With a capacity of more than 3500 passengers and crew on board, and often adverse weather conditions, an aerial rescue mission is next to impossible. Response capabilities of Australia and New Zealand, for example, are very limited (Jabour, 2007).

Sustainable tourism and the polar regions

After the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) published the report Our Common Future, also commonly referred to as the Brundtland Report in 1987, sustainable tourism became the lofty goal of many tour operators, regional governmental organizations (RGOs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as pressure groups and various industry organizations (Lück, 1998). Sustainability is defined as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (WCED, 19...