![]()

1

Setting the Stage

This book was inspired by unease regarding the lack of progress we have made towards sustainable development,1 despite numerous activities carried out by government agencies, research laboratories, environmental organizations, neighbourhood councils and the like. It would be difficult indeed to defend that only little energy and thought has been dedicated to developing sustainable solutions. After all, we now have hybrid cars, e-government, Earth Days and Earth Summits, Ride Your Bike campaigns, photovoltaics and 6022 books on sustainable development in the US Library of Congress.2 In short: much has been done, but not much has been achieved. The United Nations’ General Assembly, in preparation for the Johannesburg summit Rio +10, enunciates the same impression much more eloquently:

We are deeply concerned that, despite the many successful and continuing efforts. . . the environment and the natural resource base. . . continue to deteriorate at an alarming rate. United Nations General Assembly 55th session, 2001, p1

This book is an invitation to imagine that the problem might not rest so much with the number of activities we undertake in the name of sustainable development but – at least also – with the type of activities. ‘A story of Asterix, not of Hercules’3 as Kemp (personal communication, 26 August, 2004) describes the transition to sustainability. This is the lesson I suggest can be learned from several notable cases in which communities achieved substantial advancements with respect to sustainability, cases that are described in this book. What I encountered were not successful attempts to devise vastly more efficient technologies, nor did I find increased sustainable behaviour due to resounding awareness campaigns. These two approaches could quite rightly have been expected. After all, they represent the two poles of a spectrum I found helpful in describing the current discourse on sustainable development. It reaches from technology orientated approaches to behaviour orientated approaches. Cognate vocabularies range from modern to antimodern, from genetically modified organisms (GMOs) to eco-farming, from technophilic to sociophilic, from high-tech to back-to-the-roots. The technology orientated approach promises that smart technologies can take care of our unsustainabilities. Thus unencumbered, individuals would not have to change

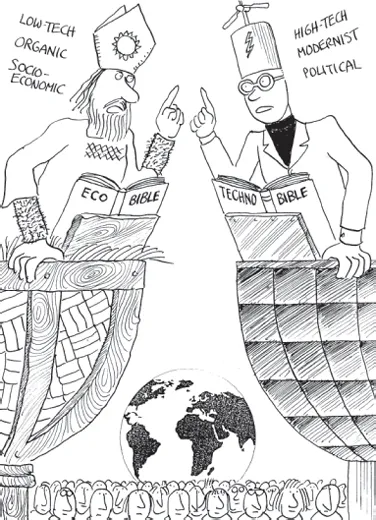

their behaviour, at least not to make heroic choices.4 In contrast, advocates of the behaviour orientated approach respond that technology has proven too often to be a false promise. In this view, we should face the truth that heroic choices, such as the reduction of consumption, are unavoidable if we are to be serious about sustainability. Advocates of both camps claim to serve sustainability, which leaves not only the public in a conceptual babel, as depicted poignantly by Hellman in Figure 1.1. A more thorough explanation of these two positions is presented in Chapter 2.

Without a cartoonist to hold a mirror up to us, we are rarely aware of how immersed we are in this discourse. I, for example, grew into it as a student eager to understand what others had to say about sustainable development. I adopted their vocabulary, which subsequently helped me to categorize competently – as it seemed -the manifold voices I heard. Eventually, it appeared natural that the proponents of fuel efficient cars and the advocates of reduced consumption literally sat at different tables in community meetings and at United Nations assemblies. Chapter 2 (section entitled ‘Ringing bells’) demonstrates that this dichotomy is indeed a prevalent characteristic of the sustainability discourse; after all, it is clearly evident in newspaper articles, scholarly journals, national energy saving programmes and in the pamphlets of grassroots activists.

As I document in Chapter 2 (section entitled ‘The seamless web’), authors of several disciplines have often criticized the distinction between the technical and the social realm as unwarranted. They argue that both are inextricably linked in two fundamental ways – whether these links are acknowledged or not. One link has come to be known as technological voluntarism; its proponents emphasize the possibility of human beings freely designing technologies according to their needs and desires. Technological determinists, in contrast, claim that existing technologies establish corridors of choices that restrict or widen the choices of individuals and of society as a whole. Science and technology studies (STS) scholars go one step further in their assertion that the relationship between the technical and the social realm is actually a constant back and forth, a circular mutual influence.

Some projects that are described throughout this book appear to have harnessed this phenomenon by proactively coordinating and synchronizing technical and social change instead of playing the oscillation game of action, re-action, re-reaction and so forth. Their designers, in most cases teams of community officials, entrepreneurs and citizens, thus managed to escape the technology-behaviour dichotomy.

While the inspiration and evidence that form the backbone of this book stem from a number of real world cases, two cases are looked at in more detail in order to learn not only what has been done but also how it has been done. Chapter 3 contains a detailed account of these cases but as a frame of reference a brief summary might be helpful at this point.

The Belgian city of Hasselt used to suffer from severe traffic related problems such as accidents, traffic congestion, low mobility for senior citizens, poor accessibility of the shopping district in the centre of the city especially for out-of-town customers, etc. Eventually, the city council opted to narrow the traffic artery

in the inner city, to increase public transport services eightfold, to radically modernize its bus fleet, to introduce a five-minute interval on some bus routes and to make bus travel free of charge. As a result, many people quickly changed their behaviour, such that bus use octupled.

Source: Hellman, 2002, p4

Figure 1.1 Competing sustainability bibles

In the second case, in the German county of Fürstenfeldbruck many people changed their shopping behaviour. They now buy more locally produced groceries because they are available at almost every supermarket, they are fresher than

non-locally produced food products, they are easily identifiable by a uniform logo, they are produced according to strict and strictly controlled standards and they are quite reasonably priced. As a result, over 800 tonnes of bread and almost 300,000 litres of milk were sold with the ‘Brucker Land’ logo in 2001.

In both cases, people changed their behaviour and new technologies,5 infrastructures or logistics systems were introduced. This twin change is hard to describe completely and concisely through either the technology orientated or the behaviour orientated terminology, as I demonstrate in Chapter 4. A manifest conclusion of this observation is that a vocabulary that cannot successfully describe existing cases should not be expected to excel in describing, ergo suggesting, future ones. The apparent need for a new vocabulary in this regard is met by recent developments in the field of STS, which turn the observation of a circular mutual influence between the technical and the social realm into a positive reference. Rohracher and Ornetzeder, for example, suggest the expression ‘fruitful co-evolution between technology design and use’ (2002, p74) and Guy and Shove talk about ‘co-evolution of social and technical systems’ (2000, p131). This language of co-evolution permits not only a more coherent description of the cases in Hasselt and Fürstenfeldbruck, but also enables us to semantically and conceptually grasp the condition of unsustainability in a different way. From this new outlook, fresh options for action become visible that harness the insights of both theory and empirical research and proceed from disavowed to strategic co-evolution, from an unavoidable relationship between technology and behaviour to a constructive partnership.

As a contribution to a general theory of co-evolution towards sustainable development, I try to identify the main memes of co-evolution in Chapter 5. Memes are the cultural counterpart of the biological concept of genes or simply the essentials of human artefacts. Ideas, technologies and infrastructures with memes that make them fit for their prevailing selection environment (that is, those that solve perceived problems for their human environment) are most likely to be produced. The foremost meme of co-evolution is the deliberately coordinated evolution of technology and behaviour in a way that makes socially desired behaviour attractive. Other crucial elements of co-evolutionary projects are also identified and systematically scrutinized against the existing body of literature. Among them are the role of public participation, the diplomacy of inventiveness, social embedding strategies of new technologies, the building of critical mass to overcome path dependencies and strategic alliances between designers and users of technologies. These memes are not meant as ready-made ingredients of co-evolution. They are rather a proposal for linguistic modules to use in descriptions of co-evolutionary cases. They might also serve as digestible units of inspiration instead of one bulky chunk of thick description. Lastly, they can be used to systematically construct a definition of co-evolution, which is presented in Chapter 5 (section ‘Definition of co-evolution’).

In Chapter 6, I anticipate and respond to a number of criticisms of the concept of co-evolution. Among the allegations that try to shake the foundation of co-evolution might be the argument that co-evolution is either too radical or not radical enough, that it is doomed because either professional interests or common

sense will blind out co-evolutionary options, and that co-evolution can exacerbate unsustainable practices if people are given too much say in the design of new technologies. Representatives of other academic disciplines could assert that the concept of co-evolution is merely old wine in new bottles, while adherents of the Great Man theory of history could reply that co-evolution depends on mere chance because it only works if there happens to be a great leader around. These arguments are tackled with reference to empirical evidence and theoretical literature, thus enabling a specification of the conditions under which I claim validity for the concept of co-evolution.

One caveat seems appropriate for the claim with which I furnish my predication about co-evolution. It helps to make sense of and to linguistically grasp real world projects that pursue certain approaches to sustainability – probably without calling it co-evolution. At first, I was tempted to write ‘without knowing that it is co-evolution’, but I refrained because it would suggest that there is a pre-linguistic ‘Truth’ ‘out there’ that is co-evolution. Under such an assumption, the cases under scrutiny would have finally discovered it and successfully mirrored it, thus coming closer to the end of history. This is clearly not what I believe. To clarify this in philosophical terms: I am more concerned with the question ‘what can we do?’ than with the ontology of sustainability and with corresponding epistemological problems. My concern is much more humble and pragmatic, as in William James’ conviction that ‘the finch with the better adapted beak isn't smarter or nobler than the other finches’ (James according to Menand, 2001, p145). Similarly, an idea carrying the meme of co-evolution is not closer to how the world was ‘meant to be’ than a low emission engine or a low consumption lifestyle. To my mind, it simply has the potential to solve some problems of a society that values the ideal of sustainability. In that regard, my proposal is not at all humble. It advocates what Spinosa et al call ‘history making’. From this perspective, people who want to make history have to ‘make choices instead of simply following the drift’ (1997, p15). Sustainability strategists who put all their hopes into optimized technologies or into a large scale change of behaviour follow the drift of the prevailing sustainability discourse. Those who look up from their isolated efforts and discover options for synergies based on collaborations with the other camp, however, are on the best path to making history.

Notes

1 I do not subscribe to one ultimate definition of this concept. Rather, I argue that we are approaching sustainable development if we achieve improvements of at least one of its main three criteria without impairing any of them: integrity of local and global ecosystems, economic viability and social fairness (as determined in an undistorted public debate).

2 Online query at http://catalog.loc.gov/ on 19 January, 2005. Guided Search = (sustainable AND development) in keyword Anywhere (GKEY).

3 René Kemp during his presentation at the 4S/EASST Conference on 28 August, 2004 in Paris.

4 This expression builds upon Kenneth Boulding's term ‘heroic decisions’, which is cited in Lovins (1979, p7). I am grateful to Langdon Winner (via email, 17 December, 2002) for bringing this source to my attention.

5 It deserves mention that I do not put technology on a par with tools and machinery, which would be ‘to substitute a part for the whole’ as Mumford put it (cited in Pursell, 1994, p26).

![]()

2

The Nature of the Problem

The technical-fix approach

Advocates of the technology orientated approach to sustainable development usually do not put much trust in the likelihood that individuals will do what they should or refrain from doing what they should not do – with should being defined by sustainability experts or politicians. They rather trust in technology because it can, in the technophile's view, take care of many unsustainabilities, and because it is always obedient to its designer. Therefore, they argue that the solution lies in a large scale, qualitatively different industrial revolution focusing on ecoefficiency, high-tech ingenuity and market forces (L. Winner, personal communication, 7 March, 2002). This view is the sequel to the young Lewis Mumford's hope that technology would lead to ‘improvements in environmental, social and economic spheres’ (according to Ebersole, 1995). Concrete manifestations of this optimism range from incrementally improved resource efficiency of existing technologies such as high mileage cars and co-generation power plants, to radical technological innovations like hydrogen fuelled cars, nuclear fusion, genetic engineering or Supercritical Water Oxidation.1 Rohracher and Ornetzeder explain that most ‘architects, planners and energy experts’ are among those for whom ‘this technical strategy is the most favourable one’ (200...