![]()

Part I

The journey to today's crossroads

![]()

1

More of the same or something different?

I am sure we all remember the latest economic crisis that began in 2007. While the economists can argue about the details of whether this downturn met the official criteria to be classified as a depression or only a recession, there is no doubt we all felt and experienced the effects of a shrinking economy. Not only were millions and millions of jobs lost as organizations contracted and/or failed, the anticipated returns on investments, be it the $40K nest egg of a retired tire builder or the $50 million trust fund of an investment banker, were also greatly reduced. Today, in early 2016, the stock market is back and the unemployment levels are approaching pre-downturn levels. Some see the current state of the economy as a signal to breathe a sigh of relief because the worst of this financial downturn is, with any luck, behind us. However, along with a growing number of individuals I am beginning to look back at these repeating cycles as something different—a signal that there is something within the way we manage our organizations and make decisions that is contributing to the frequency and/or magnitude of these downturns. It is my hope that this chapter will help to answer the question posed in the chapter’s title: do those who have been entrusted with a managerial position within an organization just continue on the same path, after all that is the path of least resistance, or do we need to begin looking into an alternative route that may well lead to a different result? If we reject the first alternative, then the question becomes which alternative path? This chapter introduces a variety of perspectives and data.

Past economic trends and...?

The first perspective I want to look into is economics. While I agree that a country’s economic measures are in the aggregate and, as such, do not single out the well or badly performing organizations, what the aggregate data does provide is an indication of the health of the average business. When these indicators are down businesses, in general, are focused much more on survival and, as such, their decisions and actions will be very different than they are riding the wave of growth.

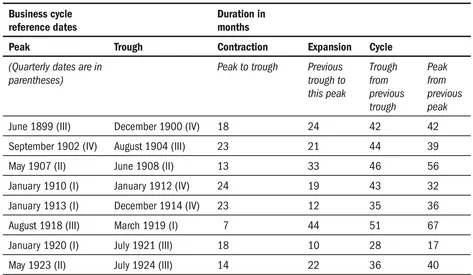

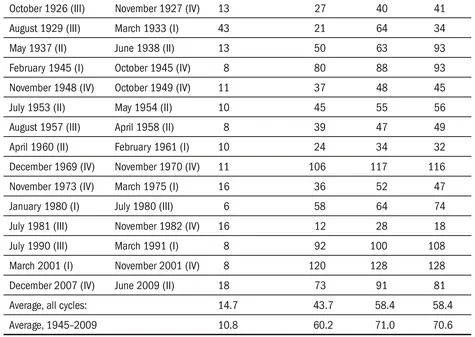

As we begin looking back at the economic data over the last 100 years there are at least two ways of viewing this data. First is the commonly accepted phenomenon that all economies experience, business cycles. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) in the United States published a table showing the timing and duration of these cycles from the mid-1850s. In Table 1 I have reproduced the NBER information covering 1900 through 2009. The two date columns on the left identify the cycle from peak (highest quarterly performance) to the following trough (lowest quarterly performance) before the next upswing. The following four columns provide additional insight (monthly measures):

- Contraction: months from peak to trough

- Expansion: months from previous trough to this peak

- Cycle measures: months from trough to trough or peak to peak

Table 1 US business cycle expansions and contractions

Source: Public Information Office, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc., Cambridge, MA (www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html).

When we take a deeper look at the data we see that the NBER identified 23 unique business cycles (measured from peak to peak) that ranged in duration from 17 months as we moved into the 1920s to the ten year cycle (128 months) that extended from July 1990 to March 2001. There are two points one should recognize when looking at this information. First, one should look at the timing/duration of the different cycles—contraction and expansion. If we take a look at the average duration of the downward (contraction) part of the cycle—from peak to trough—we see that overall it lasts about one year, whereas the upward swing (expansion) of the cycle runs for almost four years (43.7 months). A second perspective concerns the lack of any recognizable patterns in their movement except that they go up and down. The magnitudes and duration of these cycles appear to be random in nature. Yet, if this magnitude of variation appeared on the tracking of my bodily temperature or heart rate, I am sure my doctor would be frantically looking for an explanation.

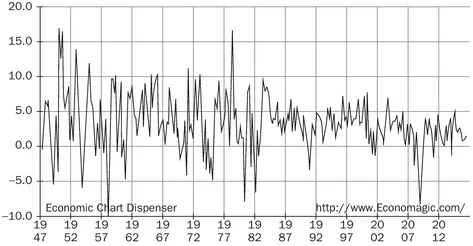

Another way of viewing economic data is to look at the magnitude of the cycle or, put another way, the impact it had on the overall economic conditions in the country. For that we will have to take a look at a different kind of data—the change in the gross domestic product (overall value of all goods and services produced by the country). This includes personal consumption, governmental purchase and expenditures, private inventories, dollars spent on construction, and the foreign trade balance (imports are subtracted and exports are added), adjusted for inflation. Figure 1 shows the percentage change in the GDP of the U.S. economy by quarter. Once again, I offer this graph as an indicator of the magnitude of impact the business cycle is having on individual businesses and as a surrogate for the intensity of the actions businesses are taking to either survive during the economic downturn or meet the increased demands during the upturns.

A quick review of the data shows that there have been 16 different occasions since 1947 that the quarterly growth of the U.S. GDP has actually fallen below zero. While this type of data tells us when and to what magnitude the quarter to quarter change occurred, it does not provide any data about what is happening within the economy. The NBER1 produces reports that dissect and provide additional details behind the summary tables and graphs, but their analysis is focused on the things that occurred during the period (quarter or year) that may have contributed to the adjustment in the GDP. While this is indeed insightful, it does not necessarily point to the causes of the change or provide us with any hard facts that can be used to better oversee and facilitate the economy’s ongoing growth.

Figure 1 Quarterly growth in real GDP at annual rates, %

Source: www.economagic.com/em-cgi/charter.exe/var/rgdp-qtrchg+1947+2016+0+0+1+290+545++0 (retrieved November 11, 2016)

Before we delve a bit deeper into trying to understand how and why the aforementioned shifts in economic performance affect organizational behavior, I think it is important to take a look at the shifts and changes in the field of economics over the last 400+ years.

To begin, let’s take a look at the concept of Mercantilism which was developed during the 1600s when the isolated feudal estates of the Middle Ages were being replaced by more centralized nation-states which had an almost insatiable desire for more wealth to support their growth. At this point in time the economists/philosophers encouraged exports and discouraged imports through the use of tariffs which, if practiced correctly, produced a positive trade balance and funneled more funds to the crown. After all, that was their goal—to facilitate the crown’s growth and prosperity.

By the mid-1700s, the physiocrats in France began expressing another economic perspective. They saw the nation’s wealth related to the size of the net products it produced. At that point in time the vast majority of the products being produced were agricultural and these were seen as the source of wealth. These economists described the economy’s “natural state” as one in which the income flows within and between the different sectors of the economy which did not expand or contract. As for structure, the physiocrats saw the economy as being composed of three different classes: productive—farmer and farm workers; sterile—industrial laborers, artisans, and merchants; and proprietor—who collected the net products as rents. Compared to the Mercantilists in Britain, the economists in France saw the structure and needs of an economy very differently.

These perspectives laid the groundwork for what is commonly referred to as the classical economics that originated in Britain in the late eighteenth century. Adam Smith is commonly seen as the father of classical economics. In 1776, the year of the American Revolution, he published a book entitled An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.2 In this seminal text, Smith lays out a multitude of ideas, but what I want to focus on is his prescription for increasing productivity. At a time when a vast majority of the items being produced were made by hand by craftspeople who started and finished one product at a time, Smith introduced the concept referred to as the division of labor, which broke the overall task down into smaller parts and assigned individuals to perform each part independently. By doing so, productivity was greatly increased and this began the transition from cottage industries to the beginning of manufacturing. This shift to businesses creating products for a market led to the need to expand the market to consume the increased level of output. Both of these shifts required an increase in capital to effectively achieve the objective of increasing productivity and growth. Another major addition from The Wealth of Nations to the field of today’s economics was included within Book 4, Chapter 2, entitled “Of Restraints upon the Importation from Foreign Countries of such Goods as can be Produced at Home”. In this chapter Smith introduces the idea of how an individual “intends only his own gain ... is ... led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was not part of his intention.”3 In this case, Smith’s metaphor was focused on showing his strong support of domestic/ local industries and comparing that to the importation of foreign-made goods. At that point in time his perspective was that the small, local economies interacting with each other and guided by the self-interest of the owners and the local community would provide a stronger economy than one that drew in imports from other countries. His position was counter to the crown-sponsored transnational organizations, such as the British East India Company and others, which tended to be unresponsive to the needs of local economies. In more recent times the idea of an “invisible hand” has been expanded by those within the neoclassical economic sphere to encompass nearly all aspects of economics.4

Another contributor to classical economics was Jean-Baptiste Say. In 1805, he published his book entitled A Treatise on Political Economy,5 which contained insights that eventually became known as Say’s Law of Markets. This theory remained part of economic thought for the next 125+ years. Say’s Law argued that there could never be a general deficiency in demand nor a general glut of commodities in the whole economy. Simply put, the objective of a businessman, when he produces a product, is to sell the product as soon as possible. After all, the sale creates wages for the worker and income for the businessman. Therefore, the production and sale of good A increases individual wealth and as such demand for goods B and C. Say recognized there could be some imbalances across economic sectors but, over time, businesses will recognize these imbalances and retool and produce products with larger demand.

The nineteenth century saw the rise of the Socialist approach to economics, most notably put forth by Karl Marx. He looked at the traditional approach to labor and its value a bit differently. He started with the currently accepted labor theory of value which defined the value of a product by the labor it took to produce it. He referred to this as the “use value” of the product. Next he pointed out that products are sold at what is called the “exchange value” which is what the customer will pay and more than the “use value”. The difference is what capitalists refer to as “profit” and Marx referred to as “surplus value”. Marx saw this as the exploitation of the worker.

Shortly after Marx published Das Kapital in 1867,6 a revolution in classical economics took place. Economists abandoned the labor theory of value which had been a tenet of economics for close to 100 years and replaced it with something new: the theory of marginal utility. This shift is commonly referred to as the marginal revolution referring to the shift to marginal utility as the primary measure. This change recognized that an equilibrium of people’s preferences established product prices, which included the price of labor, removing any question about capitalism exploiting the worker. This shift in perceptions of economic behavior led to the emergence of two very different perspectives to explain economic behavior. Let’s take a quick look at both of these:

One of the outputs from this shift was the emergence of Alfred Marshall’s work at Cambridge. He saw economics as a path to improving overall material conditions but he recognized that to accomplish this it must be done in conjunction with social and political forces. He added a great deal of insight and rigor to the field. Some of his contributions to the expanding field of economics are: the math and structure enabling the development of supply and demand graphs, the relationship between quantity and price and their effect on supply and demand, the concept of producer and consumer surpluses, and the law of diminishing returns. One of his most lasting impacts on the teaching of economics was his use of diagrams to explain the relationships between variables which he included in his text Principles, published in 1890.7

John Maynard Keynes also studied at Cambridge and is considered by many as the most influential economist of the twentieth century and one of the founders of modern macroeconomics. Prior to Keynes, the neoclassical economists believed that free markets would provide full employment in the short and medium term as long as the wage demands by the workers were flexible. Keynes argued that aggregate demand established the overall level of economic activity and if the demand was inadequate, the overall economy could see high levels of unemployment. He went on to say that intervention by the state—through spending and monitory controls—was necessary to intervene in the “boom to bust” cycles of economic activity. As the Western economies entered World War II, they begin to adopt Keynes’s economic policies. After WWII, the Bretton Woods Agreement introduced economic controls that greatly restricted the influence the speculators and financiers had enjoyed after WWI which eventually contributed to the Great Depression. By 1950, his economic policies had been adopted by most of the developed world and many of the developing nations. Indeed, the cover article of the December 31, 1965 issue of Time magazine, entitled “The Economy: We are all Keynesians now,” focused on the favorable economic conditions. It described the positive economic conditions of the mid-1960s as having been reached because of “Washington’s economic managers’ ... adherence to Keynes’s central theme: the modern capitalist economy does not automatically work at top efficiency, but can be raised to that level by the intervention and influence of the government”. It is also of note that the title of the article, “We are all Keynesians now”, is attributed to Milton Friedman, who is described as the nation’s leading conservative economist.8

The second interesting perspective was initially defined by Carl Menger in 1871. His argument for marginal utility was based on the fact that the value of goods varies because they provide differing levels of importance to different people at different times. One of Menger’s earliest followers was Friedrich von Hayek who, in his book entitled The Road to Serfdom (1944),9 argued that within centrally planned economies the individuals charged with determining the distribution of resources cannot have enough information to do it reliably. Thus they will be less effective and efficient than a free market economy. By the late 1940s Milton Friedman had arrived at the University of Chicago and continued the work of Jacob Viners and his criticism of Keynes’s approach to economics. Friedman believed that a government policy that is based on the laissez-faire approach to business was more desirable than having government intervening in the actions of business. He strongly supported the virtues of a free market economic system with few controls and minimal intervention. As for monitory policy, he thought that government should establish a hands off/neutral monetary policy that is focused on long-term economic growth and not too concerned about the short-term issues that may arise. Friedman believed that there was a close and stable association between inflation and the supply of money. That said, inflation could be avoided with the proper control and regulation of the growth rate of money within the economy. Put another way, control the amount of money in circulation and you can control the rate of inflation. His economic perspective was embraced by both President Reagan and British Prime Minister Thatcher and has received solid support from political conservatives on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

Finally, we have arrived at the latest perspective researchers have taken when looking i...