- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing Projects in Developing Countries

About this book

Covers the concepts, systems and skills of project management, identifying the three major elements of organisations: implementation, planning and procurement.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

Development and development projects

The policy framework

This book is concerned with the practical management of development projects. Development is used here in the sense that some countries are described as being ‘developed’ while others are ‘developing’ or ‘underdeveloped’. It is a concept which has become widely used only since the Second World War. A variety of theories have been advocated as the best method of achieving development. The neo-classical approach emphasized national economic growth based on investment and growth theories such as the Harrod Domar model (Sen 1970) in which particular emphasis was put on industrial expansion. The approach was dominant in the 1950s and 1960s, both in the free market and centrally planned economies. A development of the neo-classical approach was the ‘trickle-down’ theory, which suggested that all members of society would benefit from national growth, as increased wealth gradually spread from the richer sections of the community to the poorer. When this appeared not to be happening, the neo-classical approach based on industrial growth was replaced by an emphasis on the direct satisfaction of basic human needs (food, shelter, health, transport and education), particularly for the poorer members of society. The concept of development then began to assume a precise form as first, the satisfaction of basic human needs and, beyond that, as giving people the capacity to determine their own future. Throughout this period projects played a key role, because they seemed to represent the most practical method of achieving specific goals and targets in both the neo-classical and basic needs approaches, and were a way of concentrating and combining scarce human and material resources to achieve maximum effect. Indeed they were particularly appropriate to the neo-classical approach with its emphasis on the expansion of production; for a considerable time the word ‘project’ came to be associated almost exclusively with the construction of industrial, infrastructural or directly productive facilities.

The past few years have seen a shift in emphasis in development. In the 1970s and early 1980s the focus was on the study and improvement of projects as a mechanism of successful development, whether directed towards growth or the satisfaction of basic needs. In the late 1980s and early 1990s the emphasis has shifted to the study and analysis of policies, focusing on the general direction and framework of government measures, rather than specific actions represented by projects. This shift has been assisted by the increasing importance being given by the international lending agencies to balance of payments support and structural adjustment loans, and the corresponding decrease in the importance of project lending. At the same time attention is being paid to the potential of private enterprise to provide mechanisms for development, and there is a growing awareness of the need to enhance the efficiency of organizations, particularly in the public sector, through processes of institutional development.

Policies determine the environment and framework within which development takes place. Get the policies right, it is argued, and successful development will follow. Nevertheless, the tactical processes of development also need attention and, for the foreseeable future, projects are likely to form a major part of these tactics. Projects and the project approach are an instrument of policy, and are one means by which policies are put into practice. The change, which is inherent in any form of economic, institutional or social development, is brought about by initiative, impetus and, where necessary, capital investment, which may be provided by a project.

The need to link appropriate policies to appropriate projects is an increasingly important element of the development process. Whatever their shortcomings, projects will remain as an important mechanism for implementing policies: they are, and will remain, demonstrations of the effects of policies at a practical level. They also provide a means of assessing the impact of development initiatives on people. For example, a policy to attain self-sufficiency in rice may well be implemented through a series of projects related to the supply of irrigation facilities, development of improved seed, and provision of related inputs, such as training and marketing. A review of these projects, together or singly, increases our knowledge of the possible effect of the policy both on the economy and on individuals such as the farmer and the consumer. Similarly, a structural adjustment programme may include a requirement to reduce the size of the public sector. The necessary retrenchment will be affected by a series of project-type initiatives, whose impacts on identifiable individuals may be readily recognized.

Although projects in general will remain important tactical development tools, different types of projects are emerging as policy frameworks change. Hitherto, a development project has tended to mean an externally funded initiative undertaken by the public sector, generally resulting in the creation of physical assets. It is inevitable that many projects are conceived and implemented in the public sector because of the relatively large size of this sector in developing countries. Increasingly, however, projects will be internally conceived and funded initiatives, undertaken by both the public and the private sector, and often concerned as much with skill enhancement and institutional development as the creation of physical assets. Whereas the typical project of the early 1970s was the development of a sugar estate and the construction of a sugar factory, the typical project of the 1990s is management development for staff in public enterprises, or review and improvement of systems of cost recovery in water undertakings. Such projects require little, if any, physical construction work, but they are nevertheless real projects, requiring similar attention to their planning and management to be successful.

What is a project?

While the meaning and theories of development provide a general background for this book, a thorough understanding of projects is fundamental to consideration of project management. Successful project managers must fully understand the nature of projects and how these differ in many important respects from other activities in which they might become involved. Indeed, many of the problems of project development stem from an inability on the part of those involved to grasp the intrinsic differences between, for instance, a project to develop a primary health care service in a rural area, and the subsequent operation of that system.

There have been many attempts to define projects, because of their important role in the development process since the 1950s. In this context, it is valuable to use a definition which is as simple and generally relevant as possible:

A project is the investment of capital in a time-bound intervention to create productive assets.

The energy and inventiveness of people play a role in projects which is as important as the expenditure of physical and financial resources, so that in this definition ‘capital’ refers as much to human as to physical resources. Similarly, the assets created may be human, institutional or physical. This definition of a project allows us to use it across a wide spectrum of human activity. Individuals can undertake personal projects: for instance, learning a language in order to be able to use it in business or enjoy its literature is just as much a project for that individual as building a house, though the time-scale and scope of financial investment may be vastly different. More usually, we are concerned with projects undertaken by groups of individuals and society as a whole through government. In this case projects can cover a whole variety of initiatives; these may range from those designed to enhance potential in specific groups, perhaps creating small-scale enterprises for the rural poor, through projects intended to establish new organizational forms and sets of procedures, for instance for delivering health care more efficiently, to projects for the construction of physical assets such as factories. The key aspect that distinguishes a project from other forms of investment, whether for society or an individual, is that the investment is outside the scope of the normal day-to-day or year-to-year expenditure and effort, that it takes place over a particular time (in other words it is ‘time-bound’) and that it is intended to achieve a specific objective or set of objectives.

In arriving at a precise understanding of the nature of projects, it is also necessary to be aware of the link and distinction between projects and programmes. A programme resembles a project in that it is a set of activities designed to facilitate the achievement of specific objectives but generally on a larger scale and over a longer time frame. Characteristically the activities of a programme may be diverse in scope, and widely diffused, both in space and time. Examples are found right across the development spectrum. In response to the International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade (the objective of which was to provide all people with safe water and sanitation facilities) many countries formulated programmes consisting of a series of activities such as surveys of existing facilities and resource potential, procurement of necessary equipment for drilling and construction, widespread health education, training of skilled personnel, and so on. A programme in the industrial sector might be the planned expansion of plant capacity for sulphuric acid production in order to achieve the goal of making a country self-sufficient in a given time. Programmes may also mean much smaller routine or repetitive activities falling within an overall plan, such as the construction of grain stores or the allocation of money and personnel to an Irrigation Department for the rehabilitation of small irrigation schemes.

Development projects are often the constituent activities of programmes. In the case of water supply, for instance, the construction of a well for a village community would constitute a project, as would the construction of a dam and pipeline for an urban supply. In the case of industrial production, the construction of a new factory would be a project. The distinction between projects and programmes is not always clear-cut since “many characteristics are common to both activities. A project large enough in time, scope or cost may often be called a programme; integrated agricultural development programmes/projects are a case in point. Generally, however, the important distinction is that programmes are diverse sets of activities over a long period designed to attain certain objectives, while projects have a defined starting and finishing time. Projects also tend to be location-specific, though this is not invariably the case. In this book project management relates both to individual investments (projects) and programmes.

The important characteristics of projects are that they involve capital investment (through the incurring of costs) over a limited time-frame. Projects create, over that period, assets, systems, schemes or institutions, which continue in operation and yield a flow of benefits after the project has been completed. Once an individual has expended hard work, and perhaps incurred financial costs, to learn a foreign language (the project), he or she can continue to use and enjoy that knowledge. Once a water supply project has been completed (through the commitment of investment resources such as money, skills, equipment and materials), it creates a system which is operated to supply drinking water to its consumers on a continuing basis. Unfortunately development practitioners often blur the distinction between projects and the assets, systems, schemes or institutions that they create. This decreases the effectiveness of development through the project approach, because the techniques and approaches appropriate to the time-bound investment of a project are not necessarily appropriate to the continuing operation of the assets. Another problem, which frequently occurs, particularly when large quantitites of aid funds are involved, is to view them as self-contained initiatives, separate and distinct from the other activities of the organization which owns them. In fact, any organization is likely to be involved with a number of projects, as well as a collection of ongoing activities or a portfolio of continuing business. Very often there will need to be a trade-off between projects and the other activities, perhaps in relation to the commitment of scarce resources. Project managers need to be aware of the wider framework within which they are acting, and to understand that the best interests of the organization as a whole may sometimes be better served by putting first the requirements of the operation of existing assets and systems at the expense of project development of new assets. This is often made difficult because (as will be discussed on p. 8) current practices of aid funding tend to emphasize capital investment for projects, at the expense of recurrent funding for operations.

The project cycle: the traditional approach

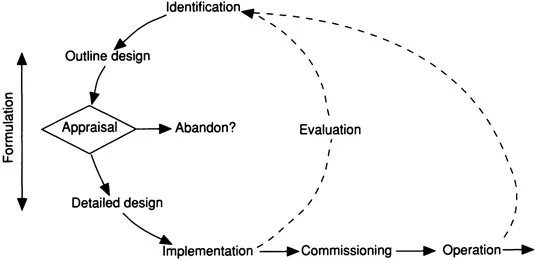

The idea of development projects as the time-bound creation of physical assets led in turn to the recognition of phases within the project process and from there to the concept of the project cycle. The following section discusses fundamental modifications to the project concept which require a major reassessment of this general approach. Nevertheless, the idea of the project cycle still has much of value for project managers, and serves as a useful basis for understanding. Many versions of the project cycle have been produced, all of them having as their basis the idea that projects go through a number of clearly defined stages in the process of their establishment. A well-known and influential version of the cycle presented in a cyclical form is that due to Baum (1978), while UNIDO (1979) have produced a linear form. Figure 1.1 presents a modified version which borrows something from both these models.

Whatever their differences, most models of the project cycle have the same basic concepts and highlight the following important stages: identification, formulation, implementation, commissioning, operation and evaluation.

Identification

Identification is the stage at which the project is defined as an idea or possibility worthy of further investigation and study. This may come about either as the result of the discovery of a resource which could be exploited (a valuable mineral deposit in a remote region) or a need or demand to be satisfied (inadequate skills in a particular group of agricultural extension workers). Of course, many more projects are identified than actually pass through the remainder of the cycle to completion and operation.

Fig. 1.1 The project cycle

Formulation

The formulation (or preparation) stage involves the definition of alternatives for the project, followed by the selection and planning of the optimum alternative, covering such aspects as size, location, technical details, markets and institutional arrangements. Thus, for a mining project, preparation would involve defining and costing the techniques and facilities required for mineral extraction and assessing the potential market and revenue, together with important environmental and institutional considerations. For the strengthening of an agricultural extension effort it would involve identification of the skills which were lacking, assessing methods of providing those skills, perhaps through a particular type of training programme, and estimating the benefits expected to accrue. Within the formulation phase certain clearly defined stages can normally be distinguished: outline design, appraisal and detailed design.

Outline design

This is the design process carried to a sufficient level of detail to allow the estimation of technical, social and institutional parameters, and the preparation of a feasibility study with an assessment of costs and benefits. This should be done ideally to accuracy of, say, 20 per cent, though lack of good data and difficulties of forecasting mean that such accuracy is often not achieved.

Appraisal

Appraisal is the process in which all aspects of the project are reviewed, in order that the decision whether or not to proceed can be made. Appraisal should cover technical, financial, economic, social and organizational aspects of the project; others, such as environmental, administrative, gender or political impacts, may also need to be considered. Where aid funds are involved, appraisal is often seen as a formal process and a clearly definable event i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Development and development projects

- Chapter 2 The Project framework and the project environment

- Chapter 3 Project management and the project manager

- Chapter 4 Project organizations

- Chapter 5 Farhad Analoui Skills of management

- Chapter 6 Project implementation planning

- Chapter 7 Procurement, contracting and the use of professional services

- Chapter 8 Project finance and financial management

- Chapter 9 Project management systems

- Chapter 10 Farhad Analoui Managing people in project organizations

- Chapter 11 Beyond projects: the wider context of management

- Chapter 12 Carolyne Dennis Current issues in development management

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Managing Projects in Developing Countries by John W. Cusworth,T. R. Franks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Project Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.