eBook - ePub

Choosing Environmental Policy

Comparing Instruments and Outcomes in the United States and Europe

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Choosing Environmental Policy

Comparing Instruments and Outcomes in the United States and Europe

About this book

The two distinct approaches to environmental policy include direct regulation-sometimes called 'command and control' policies-and regulation by economic, or market-based incentives. This book is the first to compare the costs and outcomes of these approaches by examining realworld applications. In a unique format, paired case studies from the United States and Europe contrast direct regulation on one side of the Atlantic with an incentivebased policy on the other. For example, Germany's direct regulation of SO2 emissions is compared with an incentive approach in the U.S. Direct regulation of water pollution via the U.S. Clean Water Act is contrasted with Hollands incentive-based fee system. Additional studies contrast solutions for eliminating leaded gasoline and reducing nitrogen oxide emissions, CFCs, and chlorinated solvents. The cases presented in Choosing Environmental Policy were selected to allow the sharpest, most direct comparisons of direct regulation and incentive-based strategies. In practice, environmental policy is often a mix of both types of instruments. This innovative investigation will interest scholars, students, and policymakers who want more precise information as to what kind of 'blend' will yield the most effective policy. Are incentive instruments more efficient than regulatory ones? Do regulatory policies necessarily have higher administrative costs? Are incentive policies more difficult to monitor? Are firms more likely to oppose market-based instruments or traditional regulation? These are some of the important questions the authors address, often with surprising results.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Choosing Environmental Policy by Winston Professor Harrington, Richard D. Professor Morgenstern, Thomas Professor Sterner, Winston Harrington,Richard D. Morgenstern,Thomas Sterner,Winston Professor Harrington,Richard D. Professor Morgenstern,Thomas Professor Sterner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

SO2 Emissions in Germany

Regulations to Fight Waldsterben

ONE OF THE MOST SERIOUS environmental problems in recent German history has been the decline of forest vegetation caused by air pollution, a process known as Waldsterben, “forest death.” Arousing great public attention, it coincided with (and may even have partly caused) the emergence of the Green Party in Germany. Waldsterben created enormous pressure on politicians and industry to reduce the emissions believed responsible for this environmental damage—sulfur dioxide (SO2). Because large combustion plants in the electricity sector were by far the largest source of SO2 emissions, it was obvious that these emissions had to be reduced significantly if the environmental situation was to be alleviated. Consequently, stringent regulations entitled the Großfeuerungsanlagen-Verordnung (GFA-VO, Ordinance on Large Combustion Plants) were compiled and took effect on July 1, 1983.

Following the enactment of GFA-VO, the electricity sector embarked upon a tremendous (and expensive) reduction program that led to a sharp decline in SO2 emissions. Electricity generators in the biggest German federal state, North Rhine–Westphalia, voluntarily agreed to cut emissions of SO2 and nitrogen oxides (NOx) even faster than required. Though highly ambitious, the reductions envisaged by GFA-VO and the voluntary agreement were actually exceeded.

Many economists seem to have a common opinion about the properties of command-and-control instruments like the GFA-VO: In a nutshell, they believe that such instruments are usually reasonably good at meeting the desired emissions reductions but poor at achieving the least-cost allocation of abatement activities (static efficiency) and stimulating environmentally friendly technological progress (dynamic efficiency). Against this assessment of command and control instruments the obvious success of GFA-VO in reducing emissions—but also the high costs necessary to achieve those reductions—prompt a number of questions:

1. What were the reasons for the tremendous reduction in SO2 emissions, and how important was it that the German SO2 policy relied on a command-and-control approach?

2. Were the high costs of GFA-VO attributable to the failure to achieve the efficient allocation of abatement efforts?

3. Or were the high costs due to negative effects of the command-and-control policy and its effect on technological progress?

The aim of this case study is to answer these questions—to explain why GFA-VO was successful in emission reductions and to evaluate both its static and its dynamic efficiency properties. The focus of the analysis is on SO2 emissions from existing large combustion plants (LCPs) and on the electricity generating industry, which accounts for the majority of LCPs.1

The case study is structured as follows. First, some background information about Waldsterben and the electricity sector is provided. The next sections describe the political evolution of and substance of GFA-VO and the voluntary agreement in North Rhine–Westphalia. Then, GFA-VO and the voluntary agreement in terms of emission reductions and static as well as dynamic efficiency are evaluated. The final section discusses the German SO2 policy against the background of what economists usually consider the properties of command-and-control policies.

The Environmental Problem

Waldsterben

Before the 1970s, the general concern about SO2 emissions was their effect on the environment close to the emissions location. The obvious solution was to construct tall chimney stacks that distributed the emissions over a larger area. In the 1970s it became evident that such a policy led to the deterioration of air quality and vegetation in formerly pollution-free zones. The first signs of Waldsterben appeared, and at the end of the 1970s and early 1980s it spread rapidly. By 1984, 50% of the German forests were affected, with 33% considered slightly damaged and 17% severely damaged (UBA 1994). The signs of Waldsterben were visible not only to experts but also to laypersons in many mountainous regions in Germany.

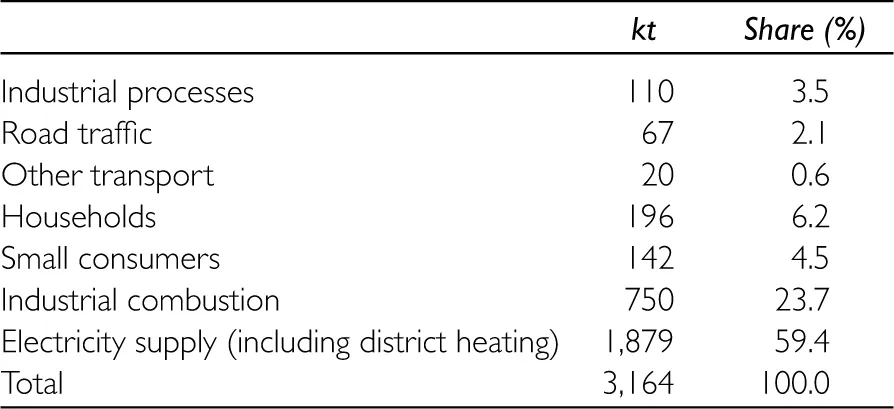

German scientists believed that high SO2 emissions were one of the main reasons for Waldsterben.2 Table 1-1 categorizes SO2 emissions in West Germany in 1980 by source.

Table 1-1. Sources of SO2 Emissions in West Germany, 1980

Source: UBA 1997, 135–39. Kt = kilotons.

Contributing close to 60% of all SO2 emissions in 1980, the electricity sector was by far the largest emitter. It was clear that substantial emissions reductions could be achieved only if the sector made significant abatement efforts. To understand the reaction of the affected industry on the demands for cutting SO2 emissions, a closer look at this sector is needed.

German Electricity Sector

Germany was and still is one of the largest electricity producers (and consumers) in the European Union. In 1986 West Germany generated 408.3 billion kWh (and consumed 386.0 billion kWh) (Statistisches Bundesamt 1991). The German electricity sector is fragmented and has a rather complex structure. Eight large companies own and operate the national high-voltage grid and the majority of generating capacity. But there are also nearly 1,000 regional and local companies that primarily distribute electricity. Although the public sector owns or holds majority shares in many of the regional and local companies, the eight large companies are dominated by private shareholders.

Prior to the recent liberalization of the European electricity markets, German electricity suppliers enjoyed regional monopolies. The sector was exempt from competition and antitrust laws. Electricity prices were fixed by electricity suppliers but had to be approved by public authorities. To raise prices, suppliers had to demonstrate a corresponding rise in production costs. The electricity suppliers began to lose this comfortable position with the 1997 European regulation on a single electricity market.

In 1997, the power stations produced 486,768 GWh (up from 355,048 GWh in 1987), which was 88.6% (84.9%) of the total electricity generated in Germany. In 1995, 79% of the electricity generated by the roughly 1,000 suppliers was produced by the largest companies, which then numbered nine.3 The approximately 80 regional suppliers provided about 10%, and the remaining 11% came from the small local utilities. For electricity distribution, however, the regional and local companies have shares of 36% and 31%, respectively. Only 33% of the electricity sold to households, companies, and public institutions came from the nine large suppliers, which often provide other suppliers with electricity instead of selling it directly to consumers.

Coal and uranium have been the main energy sources in Germany. In 1987, the sector produced 20.7% of its electricity from lignite, 29.5% from hard coal, and 36.5% from nuclear energy; 5.5% was produced from gas and 2.1% from oil. Hydroelectric power stations accounted for 5.1%. Other sources (including renewable energy sources, such as waste, wind, and solar energy) contributed less than 1% to electricity generation. Since 1987, the contributions of the energy sources have not changed significantly (Bültmann and Wätzold 2000).

Germany has large coal reserves. Because German hard coal is much more expensive than coal available on the world market, the German government has traditionally intervened to ensure that indigenous hard coal is used for electricity generation (Ikwue and Skea 1996). Between 1964 and the early 1970s, electricity suppliers were encouraged through tax benefits and subsidies to build power stations that burned hard coal. As of 1974, the use of hard coal was supported by a long-term contract between electricity suppliers and the coal industry stipulating that the electricity sector would buy 33 million to 47.5 million tons of German hard coal each year and pay a price sufficient to cover the costs of the mining companies. Electricity suppliers that ran hard coal generators got subsidies that were financed by a levy on electricity prices (Kohlepfennig). The contract expired in 1995, and the amount of hard coal the electricity sector buys and the price it pays are no longer regulated. Now the mining companies sell hard coal at world market prices but are compensated for the difference between the price they get and their production costs. The subsidies come from the federal budget and are paid for only a limited amount of coal.

National Political Response to Waldsterben: Strict Legislation

Rising concern about Waldsterben led to legislation that sought a fast and drastic reduction of SO2 emissions from the German electricity sector. The next section describes the policy process that preceded enactment of GFA-VO as well as the lead actors. The main content of the GFA-VO is then summarized.

Political Evolution of GFA-VO4

Leading Actors and Their Motives

The Bundesministerium des Inneren (BMI, Ministry of the Interior) was in charge of pollution control at the end of the 1970s. It reacted to the problem of Waldsterben and the public discussion about it by resolving to significantly reduce SO2 (and NOx) emissions. In pressing for tighter emissions limits, BMI understood that private and industrial electricity consumers would pay the pollution abatement equipment in the end, through higher electricity prices. Despite its insistence on strict emissions standards, BMI consulted with industry on feasible technological options to reduce SO2 emissions. Unlike electricity suppliers, BMI was convinced that reliable desulfurization techniques existed that could enable an emissions limit of 400 mg SO2/m3.

The industry groups involved in the discussion about GFA-VO were the electricity sector, the coal industry, and industrial associations such as the Bundesverband der deutschen Industrie. The electricity industry generally welcomed definite regulations on SO2 (and NOx) emissions at the national level. The legislation on which air pollution control policy was based at that time (TA Luft, Technical Instructions on Air Quality Control) demanded only that SO2 emissions be reduced “as much as possible.”This led to varying regulations in the German states. Nevertheless, the electricity suppliers were opposed to GFA-VO because they considered the emissions limits and deadlines too strict. They stressed that the paucity of experience with denitrification and desulfurization in Germany meant they would have to rely on Japanese experience and therefore could not guarantee compliance with the strict emissions limit (400 mg/m3 SO2). Additionally, electricity suppliers said the deadlines were too short to allow testing of desulfurization techniques in pilot plants first, and any shortcomings and optimization methods could not be discovered before the techniques had to be applied to the entire fleet of power stations (Bertram and Karger 1988). The high costs incurred in installing desulfurization techniques were less important for the electricity suppliers because they held regional monopolies and thus could rather easily transfer the costs to their customers via higher electricity prices. It was precisely this mechanism that led industry, especially energy-intensive sectors, to resist GFA-VO. Industry was afraid its international competitiveness would be jeopardized if only German companies had to pay higher electricity prices. Moreover, th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Overview: Comparing Instrument Choices

- 1. SO2 Emissions in Germany: Regulations to Fight Waldsterben

- 2. SO2 Cap-and-Trade Program in the United States: A “Living Legend” of Market Effectiveness

- 3. Industrial Water Pollution in the United States: Direct Regulation or Market Incentive?

- 4. Industrial Water Pollution in the Netherlands: A Fee-based Approach

- 5. NOx Emissions in France and Sweden: Advanced Fee Schemes versus Regulation

- 6. NOx Emissions in the United States: A Potpourri of Policies

- 7. CFCs: A Look Across Two Continents

- 8. Leaded Gasoline in the United States: The Breakthrough of Permit Trading

- 9. Leaded Gasoline in Europe: Differences in Timing and Taxes

- 10. Trichloroethylene in Europe: Ban versus Tax

- 11. Trichloroethylene in the United States: Embracing Market-Based Approaches?

- 12. Lessons from the Case Studies

- Index