- 182 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1977. The present series of essays, of which this is the first volume, attempts to describe what is going on in a particular speciality in such a way that it can be easily assimilated by workers in other branches of psychology. The essays do not provide comprehensive reviews of specialized topics: They are intended to convey new concepts and new approaches without covering in exhaustive detail all the relevant experimental work. They should be intelligible to any psychologist regardless of his field and also to the advanced undergraduate student.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tutorial Essays in Psychology by N. S. Sutherland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Experimental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Magical Number Two and the Natural Categories of Speech and Music*

James E. Cutting

Wesleyan University

and

Haskins Laboratories

Wesleyan University

and

Haskins Laboratories

Eleanor Rosch (1973) found that the Dani, a nonindustrial and nonliterate community in New Guinea, perceive certain colors and shapes in a manner functionally identical to American college sophomores. Her result is interesting because the Dani have no color terms other than those for light and dark and no terms for angular geometric figures. Her methodology is complex and not relevant to speech research; her discussion centers more on the general area of cognition than on perception, but her conclusion is central to my theme: there are salient stimuli in our environment which we perceive as prototypes of natural categories. In other words, our perceptual apparatus is geared to perceive certain stimuli better than others, and it warps a somewhat illfitting stimulus to be more like its natural prototype. Moreover, going somewhat beyond Rosch, there are distinct perceptual boundaries between these adjacent categories. The categories and boundaries are "natural" because they remain largely unmodified by learning or by environment. Rosch presented convincing evidence that natural categories exist in vision; here, I hope to demonstrate that they are prevalent in audition and are accompanied by equally "natural" boundaries. I will use findings of speech research to establish particular patterns of results indicative of "categorical" perception, and then search for them in music as well. Before presenting any data, however, I will discuss a theoretical framework in which to consider categories and boundaries.

1 The Magical Number Two in Speech Sounds

For the last two decades a certain segment of the psychological community has been persecuted by an integer. The persistence with which this number plagues those of us interested in speech perception is far more than a random accident. There is, to quote a famous senator (and perhaps a more famous psychologist), a design behind it, some pattern governing its appearance. Either there really is something profound about this number or else we are all suffering from delusions of persecution. Our number, however, is not seven; it is two.

It is no mere trick that I choose to paraphrase the first paragraph of George Miller's famous paper from Psychological Review (1956). Information processing has certainly burgeoned in the 20 years since his paper appeared, and talk of channel capacities and bits of information has since filled many books and articles. One may worry, then, that those of us interested in this smaller integer are somewhat misguided, if not stymied: perhaps each of us is only two sevenths of a proper psychologist, or perhaps our student subjects are only two-sevenths as bright as most. This is not the case (we hope). Whereas Miller is concerned with an upper limit of perceptual processing, we are interested in a lower limit. In addition, we are interested in the possible benefits derived from binary systems. In information-theory terms Miller is a three-bit researcher; we, on the other hand, are not even two-bit but rather one-bit researchers.

Psychologists and others have come very late to one-bit research, especially as it is relevant to language. Millenia before engineers and their computer science stepchildren thought in terms of binary electrical circuits, before physiologists discovered all-or-none neural firings, and before geneticists postulated dominant and recessive genes, Greek and Sanskrit grammarians were discovering the magical number two in distinctive features. These binary systems are fundamental to language: "the dichotomous scale is the pivotal principle of the linguistic structure" (Jakobson, Fant, & Halle, 1951, p. 9). Spoken language in particular is a house built on the number two (see Halle, 1957; Lane, 1966, 1967).

Consider some important binary oppositions in speech, using /ba/ as in bottle as a reference syllable. The slashes here act in a manner similar to the way a dollar sign denotes that numbers are American money: they indicate that the letters between them are spoken according to the International Phonetic Alphabet. It is reasonable that /ba/ should be considered a central utterance in a scheme of speech tokens. Unlike many speech sounds, the elements /b/ and /a/, and the syllable itself, are nearly universal to all languages of the world. A related syllable, /pa/ as in pod, is also nearly universal. Together, the two consonants /b/ and /p/ are a voiced-voiceless pair and differ only in the relative timing of the opening of the mouth and the initiation of pulsing in the larynx. For /ba/ the timing is nearly simultaneous in English, whereas for /pa/ there is a slight delay in the onset of voicing which is preceded by about a twentieth of a second of whisper. This distinction is important because there is no speech sound, or phoneme, that is intermediate between /b/ and /p/.

Another binary pair is /ba/ and /ma/, which differ in manner of production: /ma/ is nasalized, /ba/ is not, but otherwise they are identical speech sounds. When a child says "I have a cold id by doze" we can appreciate the effect of clogged nasal passages on the neutralization of this phonetic distinction. A third pair is /ba/ and /da/, which differ in place of articulation: /ba/ is labial, produced at the lips, and /da/ is alveolar in English, produced by placing the tongue on the alveolar ridge behind the teeth. Just as there is no speech sound between /ba/ and /pa/, there is none between /ba/ and /ma/ and none between /ba/ and /da/.

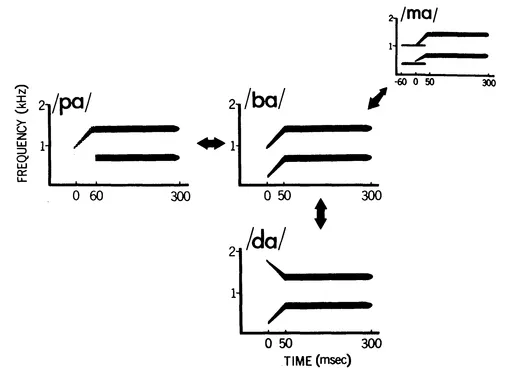

FIG. 1 Schematic spectrograms of /ba/ (as in bottle) and three other syllables whose initial consonant differs from /b/ along one phonetic feature.

Until World War II these distinctions were based on little more than 3000 years of intuition about the nature of speech production. Psychologists, wary if not skeptical of intuition and typically more interested in perception than production, did not become interested in speech until the invention of the sound spectrograph. This device transforms sound into a permanent visual record of time, frequency, and intensity patterns. (See Potter, Kopp, & Green, 1947, for elegant and detailed examples of sound spectrograms.) Shortly after the invention of this auditory-to-visual transform came its inverse, a device known as the pattern playback, which transforms a visual display into sound. Through a period of interactive experimentation with these two devices many of the important acoustic cues were discovered which separate speech sounds from one another (see Liberman, Cooper, Shankweiler, & Studdert-Kennedy, 1967, for an overview). Schematic spectrograms of the four syllables of particular interest here are shown in Fig. 1. Since the three pairs are logically orthogonal they are displayed as if in three-dimensional space. These examples are exactly like those used for the pattern playback, and would be highly intelligible (if somewhat metallic and "unnatural" sounding) when played through that device.

Observe the acoustic differences between the syllable pairs. Although all pairs are very similar, /ba/ and /pa/, for example, differ in two ways. In /pa/ the first formant, or dark resonance band of lowest frequency, has been cut back from stimulus onset by about 60 msec. Also, the excitation pattern of the second, or higher, formant has changed. Instead of being excited by a periodic glottal source in the larynx, it is excited by aperiodic or noiselike turbulances in the mouth cavity. Natural speech tokens would typically have a third and other higher formants. Whereas the third formant carries some important phonetic information, the fourth and higher formants carry little or none; the first two carry the bulk of the linguistic information load and suffice for these syllables. The syllable pair /ba/-/ma/ differs mostly in the addition of steady-state nasal resonances to /ma/. They extend from just before to just after the release of constriction at the lips (which creates the formant transitions). For /ma/, however, the first formant transition is less prominent. The differences between /ba/ and /da/ are perhaps the smallest and conceptually easiest to visualize of the three pairs. In /ba/ the second formant glides upward in frequency at syllable onset, whereas in /da/ the second formant glides downward by about the same amount. It will be instructive to consider this pair in more detail.

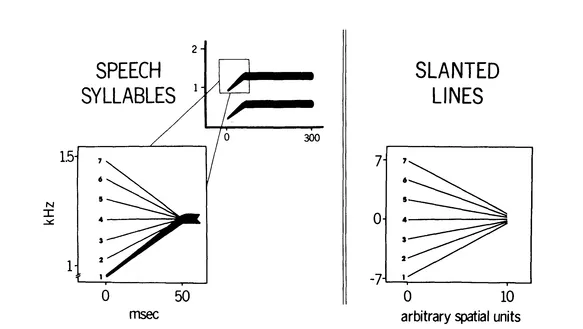

Identifying

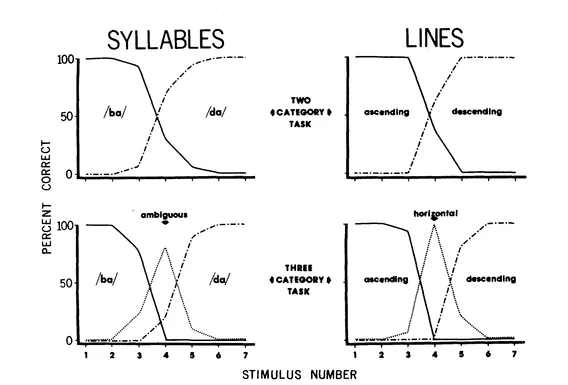

Humans have little success in producing speech sounds intermediate between /ba/ and /da/. Computer-driven speech synthesizers, on the other hand, can easily be programmed to produce these unlikely sounds. When a seven-item continuum of utterances is generated from /ba/ to /da/, the syllables array themselves as shown in the left panel of Fig. 2. When these seven syllables are randomly ordered and presented many times, and when listeners identify each as either /ba/ or /da/, we find our first empirical manifestation of the magical number two. Complementary identification functions show discrete perceptual categories as seen in the upper-left panel of Fig. 3. These are actual not idealized data. Notice that the first three stimuli in that array are almost always identified as /ba/, and that the last three items are almost always identified as /da/. (Stimulus 4 is perceived as /ba/ about half the time and /da/ the other half.) The stimulus differences appear to be perceived in a discrete rather than continuous manner.

However, one should not be overly impressed with the quantal nature of these complementary functions. Imagine an array of lines tilted at various angles like that shown at the right of Fig. 2. If we "read" these lines from left to right, Stimuli 1 through 3 might be considered "ascending" and Stimuli 5 to 7 "descending." Increments of physical difference between members of this visual array are exactly equal in angular degrees, just as increments in the /ba/-to-/da/ auditory series are equal in slope change of the second-formant transition. When the visual stimuli are mounted on cards and viewers asked to classify each as ascending or descending, we find nicely quantized identification functions shown in the upper-right panel of Fig. 3, with only Stimulus 4, the true horizontal, not a member of either category. Clearly the auditory and visual results are similar, and nothing would appear to be peculiar about speech.

FIG. 2 Schematic spectrograms of a /ba/-to-/da/ acoustic continuum, and a display of a companion array of slanted lines.

FIG. 3 Identification functions for an array of speech syllables and an array of slanted lines (shown in Fig. 2) in two conditions: one assigning the items to two categories and the other assigning them to three categories.

As a further demonstration that identification functions should not be overemphasized, consider what happens when we ask the same listener-viewer to classify the continua into three categories instead of two. The speech-syllable choices here are /ba/, "ambiguous" (not convincing as either stop consonant), and I da/; and the slanted-line categories are ascending, horizontal, and descending. Results are shown in the lower panels of Fig. 3. Both classes of stimuli yield similar identification patterns, with the third categories supplanting the old boundaries in the two-category tasks. From these results speech perception would appear to be no different from the perception of objects and events in other modalities. Moreover, the magical number two would seem irrelevant.

Two statements must be made before entertaining the notion that these conclusions are legitimate. First, the two stimulus series in question were judiciously selected. Few acoustic continua generated by a speech synthesizer appear to have phoneme boundaries with near-zero slope in the second-formant transition: /ba/-to-/da/ is closer to being an exception than the rule. Deviations from the peculiar regularity in this syllable array, such as that found in a /bi/-to-/di/ acoustic continuum (as in beam to deem), would be much more difficult to model in a visual continuum. Second, we should consider the nature of the middle categories in each set of responses. Intuitively they seem quite different. The middle visual category would appear psychologically more real than its neighbors. Indeed, the terms ascending and descending are derived with reference to horizontal. The middle speech syllable category, on the other hand, is a tenuous if not bogus domain. Certainly /ba/ and /da/ are not derived perceptually with reference to an ambiguous stimulus which is difficult if not impossible to pronounce. In short, we see horizontal lines every day; we do not "hear" ambiguous speech sounds. Just as with a Necker cube, the percept flips one way or the other: it is either /ba/ or /da/, and rarely anything else unless one asks the subjects to perform the unusual task of "ambiguating" the syllables as I have done.

Discriminating

Given these clues that a /ba/-to-/da/ acoustic continuum is perceived somehow in a unique and quantal manner, we should look to a second and more important manifestation of the magical number two—nonlinearities in discriminability.

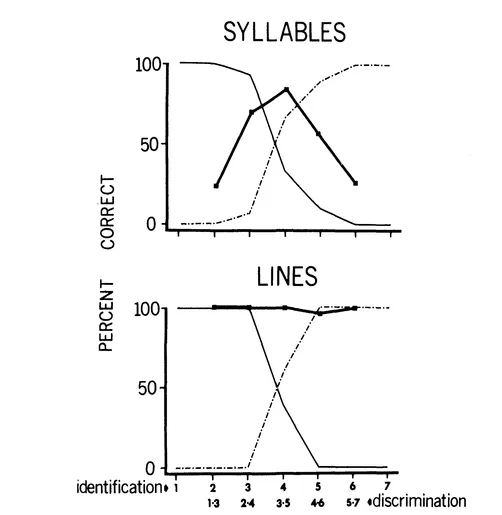

If a listener-viewer is asked to compare two members of one of the arrays of stimuli used thus far, how accurate are her responses? For purposes of uniformity both arrays of stimuli are presented in a sequential discrimination task: the first stimulus is presented, followed by a silent or blank interval of one second, followed by the second stimulus (either identical to the first or two steps removed along the physical continuum). In this manner, along with item pairs which are identical, Stimuli 1 and 3 are compared; 2 and 4; 3 and 5; 4 and 6; and 5 and 7. Subjects are asked to report whether the two items are the same or different. Only the "different''-pair results are of interest here and are shown in Fig. 4; few errors occur on "same"-pair discriminations in this type of task. Notice the sharp discrepancy between the two darker functions. The speech syllable data, shown in the top panel, demonstrate a sharp peak in discriminability at the Stimulus 3-Stimulus 5 comparison which rapidly tapers to lower-than-chance performance at either end of the continuum. The slanted line function, on the other hand, is at or near 100% performance throughout the stimulus range. (Smaller increments between slanted lines could easily decrease performance level, perhaps even create a peak near the horizontal, but significant troughs are unlikely to occur.)

FIG. 4 Two-step discrimination functions for speech syllables and slanted lines, superimposed on their respective identification functions.

Comparing these discrimination results with the two-category identification functions superimposed upon them, we see that for the speech items there is a correspondence between the crossover of the complementary identification curves and the peak in the discrimination function. Labelability changes inversely with discriminability: Items can only be perceived as distinct from one another when they have different names. This nonlinearity lies at the heart of the interest in th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. The Magical Number Two and the Natural Categories of Speech and Music

- 2. Word Recognition

- 3. Psycholinguistics Without Linguistics

- 4. Psychological Treatment of Phobias

- Author Index

- Subject Index