eBook - ePub

The Foundation of Literacy

The Child's Acquisition of the Alphabetic Principle

- 162 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This monograph brings together important research that the author and his colleagues at the University of New England have been conducting into the early stages of reading development, and makes a valuable contribution to the debate about literacy education. It should appeal to a broad audience since it is written in an entertaining and accessible style, with chapter summaries, and where appropriate short tutorials in relevant topics, in particular Learnability Theory (Chapter 1), levels of language structure (Chapter 2) and writing systems (Chapter 2).

It will be of interest to experimental psychologists concerned with the reading process, developmental psychologists interested in cognitive growth, educational psychologists interested in the application of experimental methods in the classroom situation, and teachers and teacher educators.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Foundation of Literacy by Brian Byrne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Definitions, phenomena, questions, and frameworks

DEFINING THE ALPHABETIC PRINCIPLE

The term alphabetic principle refers to the relatively straightforward idea that the letters that comprise our printed language stand for the individual sounds that comprise our spoken language. Consider two simple words of English, dog and den. Both of these have three letters. This is motivated by the fact that both have three sounds. Both start with the same letter. This is motivated by the fact that both start with the same sound. For the same reasons, mad ends with the letter these words start with, and shares its first and second letters with man. In general, whenever and wherever a particular sound occurs in a spoken word, it can be represented by a particular letter.

To readers of this book, literate adults all, the fact that dog and den each has three letters and the fact that each starts with the same letter are unremarkable ones—trivial even. Here, however, is what I want to demonstrate about the alphabetic principle in this book: To apprentice readers, it is far from obvious why words like dog and den are written the way they are, and discovering why they are is not trivially easy. Children will not, for the most part, make the discovery unaided, and the consequences for literacy growth of not discovering the alphabetic principle are serious. It follows that instructional methods that assume that the alphabetic principle need not be a prime, early focus, that it is obvious or trivially easy to discover, are ill-founded.

Readers familiar with phonology, phonetics, and speech science will note some oversimplifications in how I have defined the alphabetic principle. One is the use of the phrase individual sounds. It implies discrete packages of acoustic energy, but discreteness is not in fact a property of the elements of speech. Another oversimplification attends the adjective same (sound). It implies invariance, such that, say, the vowels a in the words mad and man are acoustically identical. They are not. I recognise these and other shortcomings in my definition, and I will address the ways in which these are oversimplifications as we proceed. Indeed, the simplifications themselves may embody some of the reasons why some children find discovery of the alphabetic principle to be a difficult assignment, as we will see. But the definition will suffice for the moment; it successfully describes the core feature of an alphabetic writing system. This monograph is about how children come to understand that feature. It is also about the consequences of achieving, and not achieving, a grasp of the alphabetic principle.

Others will note that the definition also oversimplifies the nature of one version of an alphabetic writing system, English. It is true that in English dog has three sounds and three letters, but ship has three sounds and four letters and ox has three sounds and two letters. It is also true that the words weather, whether, and wether all sound the same but are spelled differently. Inconsistencies and irregularities in English spelling abound, and we consider some of these later in the book. Nevertheless, English is fundamentally an alphabetic language and thus furnishes proper material for a book about the child’s discovery of the alphabetic principle.

DETECTING THE ALPHABETIC PRINCIPLE

For the most part, we will consider the alphabetic principle to be in place in children who can decode novel print sequences, exemplified by nonwords like sut and yilt that they could not have learned “by sight”. Unless children know why writing has the form that it does, they are unlikely to be able to make sense of print sequences they have not seen before. But it needs to be said at the outset that children could in principle understand why dog and den are written the way they are and yet not be able to decode new words. Put the opposite way, a failure to decode does not necessarily mean that a child has failed to grasp the alphabetic principle. Indeed, we will see evidence that this dissociation may sometimes occur. Nevertheless, as I will argue, the ability to decode is a product of understanding the alphabetic principle, and it underpins literacy growth. Hence, decoding can be used as a touchstone for the presence of the alphabetic principle in children’s minds.

Moreover, though this is rather obvious, children could know how to read dog and den but not understand why they are written the way they are. They could read them in roughly the same way as you and I read $ and & and %, by rote, without relying on any links between the individual letters and individual sounds within the words. In the case of &, there are none of these “sublexical” links; for a given child reading dog, there may be none either. The word might have been learned as a whole pattern, for example.

WHY STUDY THE ACQUISITION OF THE ALPHABETIC PRINCIPLE?

The answer to the question of why we should study acquisition of the alphabetic principle may seem obvious: English is written alphabetically, and therefore the ability to decode it, an ability essential for reading English, is based on an appreciation of the alphabetic principle. Moreover, it follows from this that we should investigate the best way to teach the alphabetic principle. But it is important to note that the first claim, that people employ the alphabetic principle during reading, is an empirical rather than a logical one. It does not follow automatically from the fact that English itself employs an alphabet. We have already granted that it is possible in principle to read words and not know why they are written the way they are. A good test of this kind of “rote” reading would indeed be whether the person can decode nonwords. If they cannot, their success with real words is probably based on rote associations between printed and spoken words. Rote associations of this sort would seem to place high demands on visual memory, given that different words share many common letters and letter groups. But humans are pretty good at remembering, say, thousands of faces, which also share many overlapping features. We could also say that this kind of rote reading would place special demands on instruction, requiring a teacher to tell the child what each printed word says. But this observation does not amount to an argument that rote learning cannot occur. In fact, case reports document the existence of people who can read reasonably well but are simultaneously poor at decoding. There are not many of these reports, and reading performance may be seen to be compromised on close examination. Nevertheless, their existence indicates that decoding, the ability to pronounce unlearned letter strings, may not be necessary for reading real words and the texts made from them. For an example of this kind of case and a summary of others, see Stothard, Snowling, and Hulme (1996).

Assume for the moment, however, that understanding the alphabetic principle is basic to reading English. Then we can turn to the second part of my answer as to why we should study acquisition of the alphabetic principle, namely to discover the best way to teach it. But it is not a priori obvious that we need to teach it at all, at least if we mean by teach to provide children with direct instruction. Whether we need to do so for the alphabetic principle is also an empirical question. Alphabetic writing is simply a set of rules relating letters to sounds, and humans are rather good at learning rules without direct instruction. Spoken language is probably the best example of this: Speakers create sentences and discourses under the control of complex rules and principles that they have never been taught in any overt way. Similarly, readers may learn the rules for pronouncing novel strings of letters without being directly taught how to do so. Young children acquire the structures and rules of spoken language without conscious effort and without explicit instruction once they are in an environment where language is used in a meaningful way. So young readers might acquire the principles and rules underlying alphabetic script without conscious effort simply from learning to read meaningful words written alphabetically. It may be unnecessary, or even futile, to try to teach the alphabetic principle directly, as seems to be the case for the rules of spoken language.

Thus, reading real words does not logically require a grasp of the alphabetic principle, and even if it did, understanding the alphabetic principle does not logically depend on direct instruction. The existence and nature of any links among these processes is an empirical question. We began our work with the reasonable assumption that these links exist, supported of course by the available research evidence (for a recent and particularly comprehensive survey of this evidence, see Share, 1995). We believed, in other words, that reading in an alphabetic orthography and understanding its basic design principle go hand in hand, and that this understanding needs to be taught. The questions of how use, understanding, and acquisition are linked remains, however, fundamentally empirical.

AN EXERCISE

Let us now turn to an exercise that provides a phenomenological introduction to the topic of the book. Phenomenology might seem an odd way to start a monograph in the tradition of experimental psychology, but to us literate adults the alphabetic principle seems so patently obvious that we have difficulty appreciating that children might have any problem in discovering it. The exercise is designed to help us recreate why there may be a problem. Afterwards, we move onto more solid ground with a summary of experiments on adults, which, like the exercise, are meant as an analogue to acquisition of the alphabetic principle by children. Finally in this chapter, we firm up the issues raised to that point and the questions that will be addressed in the rest of the book. We do so by selecting a framework for questions about the acquisition of knowledge in general, namely a version of what has become known as Learnability Theory.

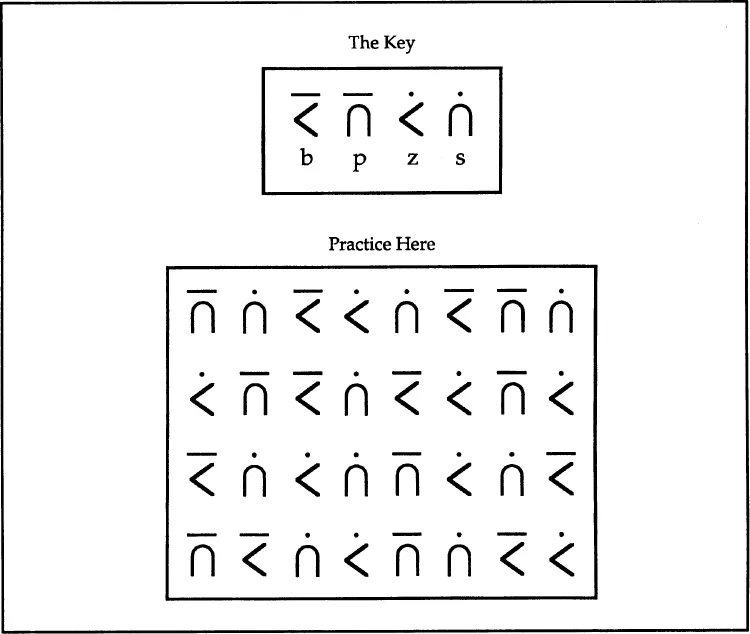

In the top panel of Fig. 1.1 there is a fragment of a new writing system. Each of the four symbols represents a consonant of English. Your task is to learn to read this new orthography by practising on the lower panel of Fig. 1.1. Simply say the phoneme corresponding to each symbol in turn. (You will have to pronounce /b/1 and /p/ with a following vowel, as in “buh” and “puh”.) At first, you will need to check back to the top part of the figure, but soon you should have the symbol-sound correspondences memorised. Keep practising until you are a fluent reader of this new orthography. Once you know the system, turn to Fig. 1.2 and try to answer the questions there.

FIG. 1.1. A new orthography. Practise pronouncing the symbols in the lower panel, referring to the key in the top panel. Continue practising until you are so fluent at saying the phoneme for each symbol that you can quickly read a whole line without referring to the key.

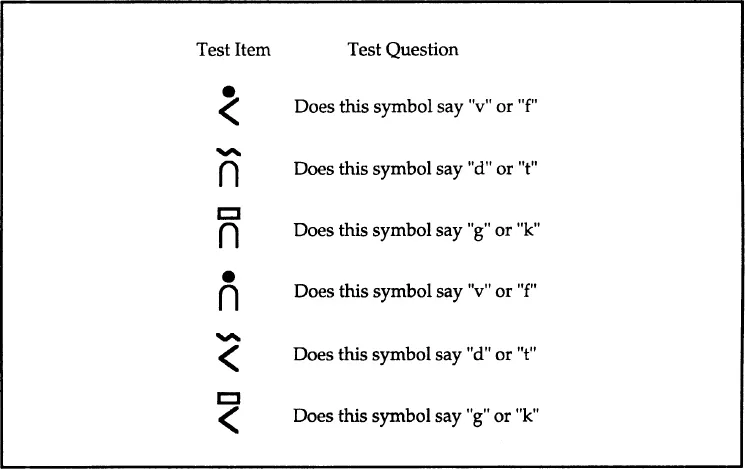

FIG. 1.2. Transfer test for the new orthography.

Were you successful?2 If you are not familiar with phonetics, and if you are like the majority of the subjects in experiments I will describe shortly, you probably were not successful with the questions in Fig. 1.2. In fact, you probably feel there are no sensible answers to those questions. But there are. The elements of the new orthography systematically represent properties of speech. Note that /b/ and /z/ share a symbol, <, as do /p/ and /s/, ∩. In speech, /b/ and /z/ have something in common; they are both voiced. This means that the vocal chords are engaged when we say them. You can notice this most clearly with /z/. Hold your finger to your Adam’s apple and say a prolonged /z/ (ZZZZZ…). Then say a prolonged /s/. Do you feel the difference? There is vibration in the larynx for /z/, but not for /s/; the sound /z/ is voiced, /s/ is unvoiced. Similarly, /b/ is voiced and /p/ is unvoiced. Put another way, /b/ and /z/ share the property of +voice, and /p/ and /s/ share the property of −voice.

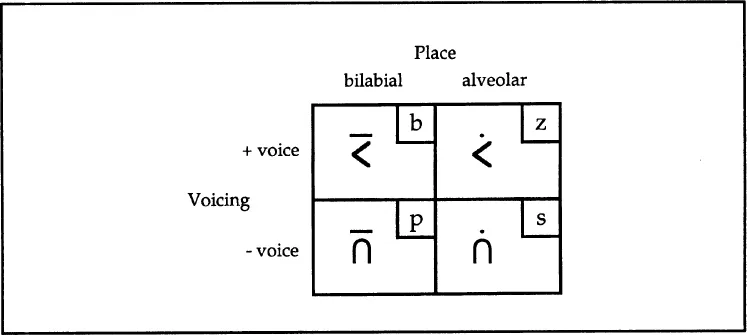

Note, too, that except for voicing, /b/ and /p/ are made in identical ways, with the closed lips suddenly parting. They are created at the same place in the vocal cavity, they are bilabials. Similarly, /z/ and /s/ are made in identical ways (except for voicing), with a hissing sound from a groove made by the tongue at the alveolar ridge behind the top teeth. They are alveolars. The alveolar ridge is these sounds’ place of articulation. The whole scheme (or the part of it that is relevant to our story) can be represented as in Fig. 1.3. The new writing system represents voicing and place: < for voiced sounds and ∩ for unvoiced ones; – for bilabials and • for alveolars. Therefore, you could in principle successfully decide that the first symbol in Fig. 1.2 says /v/ rather than /f/ as long as (1) you had deduced that voicing was represented in the new orthography and (2) you realised that /v/ is the voiced member of the otherwise identical pair, /v/ and /f/. The fact that the upper part of the symbol was unfamiliar should not have proved an insurmountable difficulty because you could choose from the alternatives offered solely on the basis of voicing. Similarly, the second symbol in Fig. 1.2 must be /t/, the unvoiced member of the /d/ - /t/ pair, and so on.

FIG. 1.3. Structure of the new orthography: How the symbols represent phonetic features. /b/ is a voiced bilabial /p/ is an unvoiced bilabial /z/ is a voiced alveolar /s/ is an unvoiced alveolar.

I have challenged you with this exercise for several reasons. One is to help you appreciate the task facing the child learning to read. Three observations are pertinent as we try to put ourselves in the mental shoes of the apprentice reader. One is that writing is first and foremost about the sounds of language, not the meanings. It is mainly about the physical, not semantic, properties of speech. For literate adults, the meanings of written words are so immediately upon us that we tend to forget this fact. Words like dog and cat bring the creatures to mind straight away. With evocative words like vomit and kiss, the meaning response is even more obvious. If we can so readily bypass the fact that print records sounds, perhaps children might have problems realising this fact in the first place. In Chapter 2, I present evidence that this is precisely what happens.

A second observation is that writing systems represent speech at more than one level simultaneously. The symbols in Fig. 1.1 stand both for whole phonemes and for elements of phonemes. The very first symbol, for instance, represents /b/ when considered as an entire pattern, and the features of voicing and bilabiality when considered component by component. Duality of representation also holds for alphabetic writing. The visual pattern dog, for instance, represents both the entire word “dog” and the phonemes /d/, /p/ and /g/. Formally, we can say that any writing system that is isomorphic with a particular level of speech is also isomorphic with all higher levels, where by “higher level” we mean the combination of elements from the initial level. So the writing in Fig. 1.1, whose elements represent phonetic features, also represents combinations of features, that is, phonemes. Alphabets, whose elements represent phonemes, also represent combinations of phonemes, that is, words.

The third observation that may help you to appreciate what the apprentice reader faces is that a learner can acquire the associations between a writing system and speech at a level other than the most fine-grained one available. This will be clear to you if you failed to make headway with...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1. Definitions, phenomena, questions, and frameworks

- 2. Children’s initial hypotheses about alphabetic script

- 3. Induction of the alphabetic principle?

- 4. Instruction in the alphabetic principle

- 5. Individual differences

- 6. Conclusions and implications

- References

- Author index

- Subject index