![]()

p.1

PART I

Breaking the shackles of gender-related expectations

Assessing and acknowledging reality

![]()

p.3

1

THE GLOBAL VIEW OF GENDER DISCRIMINATION IN BUSINESS

A story of economic exclusion

Laurel Steinfield and Linda Scott

Introduction

Collectively, women are the largest group in the world that face discrimination. Gender inequalities are a global phenomenon that occur inside and outside of the workplace. As this chapter will detail through a review of global data, the aggregated trends are consistent: women in businesses and leadership are faced with unequal career progression and unequal pay, as well as significant gaps in access to capital, all around the world. Moreover, these inequalities increase as women in organizations progress up the leadership chain and into higher tiered management positions. For entrepreneurs, these inequalities are made visible through their lack of access to financing and under-representation in more lucrative industries. As we argue, the pervasiveness of this problem means, firstly, that it is not an individual performance or capabilities issue with the “woman” who needs to “lean in.” Rather, it is a result of patriarchal biases imbedded in institutional structure, practices, policies, and imperatively, our own minds and implicit biases. Secondly, it is not just about employment or leadership or entrepreneurship as the trends we show repeat across each of these fields. Instead, there is a more systemic problem: the economic exclusion of women. Gender discrimination in business and leadership translates into a lack of access to positions of power where financial decisions are made. The wage gap, limitations on capital for entrepreneurial endeavors, and their exclusion from more profitable industries lead to a reduction of women’s investment power and ability to challenge men’s control over the global financial system. We raise concerns that go beyond the boardroom and C-suite to question the capital gap between women and men and its implications for women and economies. We interrogate policies and practices that are often believed to be solutions, such as maternity leaves or mentoring programs, and suggest plausible adjustments and actions for business and policy makers.

p.4

The data

The data we use is taken from the available records of large non-governmental bodies, including the World Economic Forum (WEF) (such as its Global Gender Gap Reports), the World Bank’s database and Enterprise surveys, the OECD and its Social Institution and Gender Index, the UNDP (United Nations Development Program), and the ILO (International Labor Organization) that have been collected annually for almost a decade. We likewise include findings based on our review of the academic literature, results from the World Values Survey (done every five years), and intermittent reports produced by the World Bank, OECD, IMF, Economist Intelligence Unit, WEF, and Booz & Company’s (now called strategy&) work on the Third Billion. Additional grey papers based on corporate’s self-reporting, such as LeanIn.Org and McKinsey & Co’s Women in the Workplace, and the WEF’s Corporate Gender Gap Report (produced once off in 2010), are used to provide insights into the awareness of the gender gap amongst business representatives and the existence of the often-invisible forms of gender biases in the workplace.

The trends

The exclusion of women from the formal labor markets

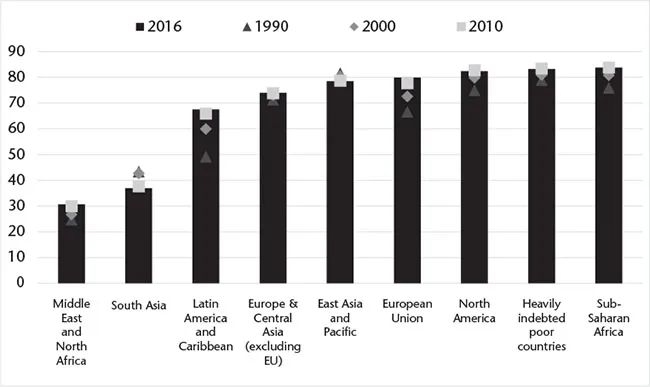

Globally, female labor force participation rates remain lower, on average, than men’s participation rates (refer to Figure 1.1). Although participation rates are comparable in some countries, especially in lower income countries, such as sub-Saharan Africa where women and men have to work out of necessity, discrepancies can be excessive in other countries, such as the MENA region (Middle East and North Africa). Imperatively, these figures mask the over-representation of women in more precarious forms of employment, such as the informal agricultural industry or part-time labor where there are fewer legal and social protections (e.g. pensions, health benefits, unemployment or maternity protection), and in sectors with lower remuneration. As the ILO’s Global Employment Trends find (2016b), women are on average 25–35% more likely to be in vulnerable employment in countries in sub-Saharan Africa and MENA region.

p.5

The downward stair-step of career progression

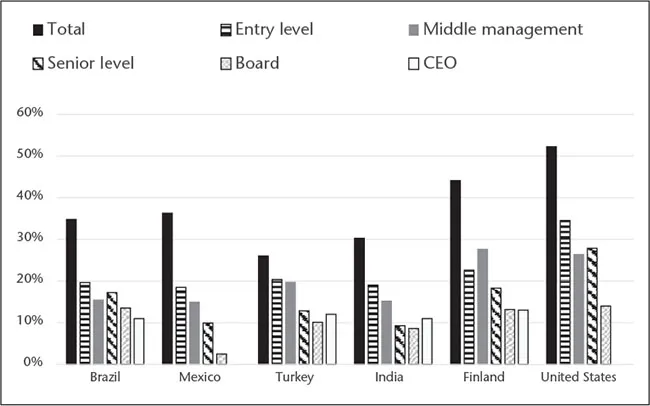

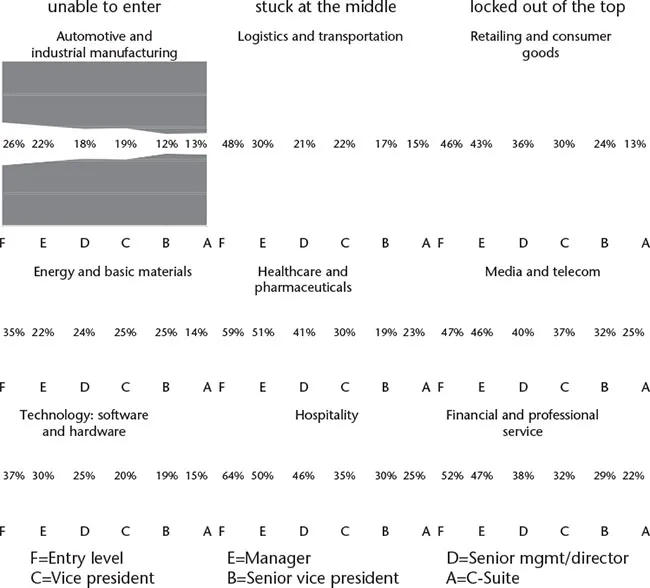

Exploring the data related to women in business and leadership demonstrates that in all nations, organizational types (corporates, governments, NGOs) and across industries, women as a population incur a downward stair-step of career progression, as well as increasing wage gaps as they move up into managerial and leadership roles. The downward stair-step, as per Figures 1.2 and 1.3, shows that although women and men may be achieving parity in labor force participation rates and gaining entry into lower level managerial positions, the ratio of women to men decreases in a stair-step fashion at each level of management, with a smaller percentage of women in middle management and a significantly smaller percentage of women in top management and on board. Figure 1.2 results are from the WEF’s (2010) Corporate Gender Gap Report—a report based on their survey with the Human Resource directors of 100 of the largest employers in the 30 OECD-member countries and BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) (3,400 companies). Notably, although the US companies have a larger proportion of women in their pipeline, these women are stuck in the middle: none of the companies interviewed had women CEOs.

p.6

The capital gap

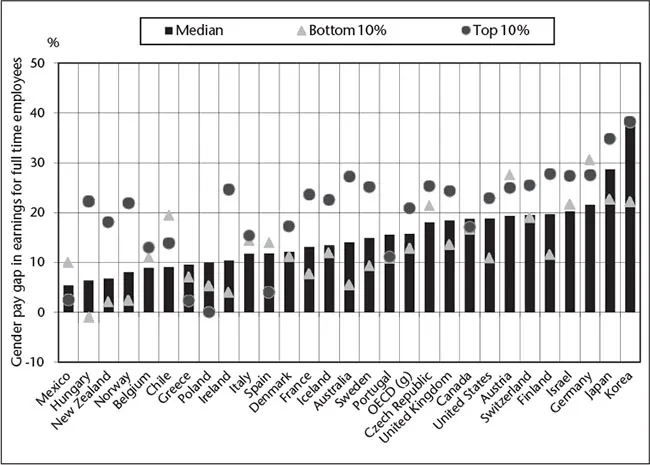

The capital gap between men and women can be seen in two critical areas: wages and access to loans. The gender gap in wages exists at every level and in every industry. Imperatively, the wage gap is the largest at the top, in management positions, where women earn on average 21% less than their male counterparts (OECD 2012). Figure 1.4 exemplifies how the gender gap is generally the largest for those women who are in the top 10% earnings category. Lower or entry level jobs tend to be graded, with information about expected pay more publicly available. As women progress in their career, knowledge about pay raises, or what the position should earn, becomes increasingly less transparent and more dependent on negotiation and subjective assessments of performance. As our subsequent review of studies demonstrates, implicit gender biases negatively affect women’s negotiations and performance-based assessments, contributing to the gender gap in pay and promotions.

p.7

p.8

The wage gap does vary by industry (as per Table 1.1). And in comparing Figure 1.3 and Table 1.1, trend lines become apparent: industries that have more women at the top or have more women as a percentage of clientele (as per the Healthcare industry or the Media/Telecom industry) report lower wage gaps. The directionality of this relationship, however, is unknown, and, moreover, it is not always guaranteed. The Financial and Professional Services, for example, which have on average 22% of their C-suite represented by women, have significant wage gaps ranging from 22–36%. The Consumer market, which has a significant percentage of a female consumer base (47%) and representation of women in their workforce (at 33%), holds the highest wage gap at 49%. Outliners such as these are important to note: they indicate a rigidity of gender biases. Indeed, prior studies show that having more women in a job can increase wage gaps because “women’s work” is undervalued. Elvira and Graham (2002) in their study of Fortune 500 financial corporations, found that for every 10% increase in the proportion of females in a job, individual employees in that job received 1% less in base salary and in total compensation, were 8.4% less likely to get a bonus, and, when given, received 7.5% less in incentive bonuses.

p.9

TABLE 1.1 The gender gap in wages versus female share of customer base, by industry

Source: WEF 2016b, 2.

In regard to loans, studies have produced mixed results as to whether women face discrimination in accessing loans and higher interest rates. Many studies report that women entrepreneurs do not request financing as much as men (see for example Moro, Wisniewski, and Mantovani 2017), yet these studies (and many that control for other “variables,” e.g. size of business, geography, etc.), fail to consider whether women are really choosing to refrain from financing or if the markets are choosing for them. Studies show that within the market there are hostile and discriminatory practices and gender biases that limit women’s credit histories and asset bases. These act to push women away from high-asset, high-investment industries (refer to McAdam 2013 for a review). In microfinance, for example, women face a glass ceiling in accessing sufficient capital (Agier 2013), which constrains the ambits of their entrepreneurial ventures. The smaller scale of women’s ventures contributes to substantially lower earnings, with self-employed women earning on average 30–40% less than their male counterparts (OECD 2012). The espoused factors of “limited management experience” and the devotion of “less time to their businesses than men” (ibid., p. 16) underscores more systemic issues at play, including a woman’s access to experience, to networks, and societal expectations of how she should be spending her time. This is a global problem.

p.10

Across the world there is a pattern in which a lower amount of financing is given to women entrepreneurs. This trend exists in developed and developing countries alike, and in countries with more liberal versus restrictive policies for women owned businesses. For example, in Lebanon, which has restrictions that limit women’s participation in the economy, 33.5% of SME businesses had women as part- or full-owners yet only 3% of bank loans went to women (IFC 2013a; OECD 2014). In the US, where its Equal Credit Opportunity Act (1974) has “led the way in nondiscrimination in access to credit” (World Bank 2015, 18), similar numbers are recorded: in 2012 women-owned businesses made up 30% of small businesses2 yet accounted for only 4.4% of the value of loans from all sources (Cantwell 2014). This financing gap exists across types of capital, getting progressively worse as it moves from financial institutions with more female representation, such as crowdfunding, (Marom, Robb, and Sade 2016) to male dominated institutions (i.e. venture capital) (Zarya 2017) where capital investment requests tend to be higher. Statistics available at a global level on developing and emerging economies likewise reflect a similar trend as per Figure 1.5. These results would argue that it is not that women do not need financing but that they are being excluded from financial markets and limited in how, where, and when they can contribute to economies.

p.11

The perceived causes: qualification gaps, laws, traditions, media, and biology

Qualification gaps

A common cause attributed to women’s stalled career progressions is that women’s levels of qualifications are not com...