- 788 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

10th Annual Conference Cognitive Science Society Pod

About this book

First Published in 1988. A collection of papers, presentations and poster summaries from the tenth annual conference of the Cognitive Science Society in Montreal, Canada August 1988.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access 10th Annual Conference Cognitive Science Society Pod by Cognitive Science Society in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Recursive Auto-Associative Memory: Devising Compositional Distributed Representations

Jordan Pollack

Computing Research Laboratory

New Mexico State University

New Mexico State University

INTRODUCTION

A major outstanding problem for connectionist models is the representation of variable-sized recursive and sequential data structures, such as trees and stacks, in fixed-resource systems. Such representational schemes are crucial to efforts in modeling high-level cognitive faculties, such as Natural Language processing. Pure connectionism has thus far generated somewhat unsatisfying systems in this domain, for example, which parse fixed length sentences (Cottrell, 1985; Fanty 1985; Selman, 1985; Hanson & Kegl, 1987), or flat ones (McClelland & Kawamoto, 1986).1

Thus, one of the main attacks on connectionism has been on the inadequacy of its representations, especially on their lack of compositionality (Fodor & Pylyshyn, 1988).

However, some design work has been done on general-purpose distributed representations with limited capacity for sequential or recursive structures. For example, Touretzky has developed a coarse-coded memory system and used it both in a production system (Touretzky & Hinton, 1985) and in two other symbolic processes (Touretzky, 1986ab). In the past-tense model, Rumelhart and McClelland (1986) developed an implicitly sequential representation, where a pattern of well-formed overlapping triples could be interpreted as a sequence.

Although both representations were successful for their prescribed tasks, there remain some problems.

• First, a large amount of human effort was involved in the design, compression and tuning of these representations.

• Second, both require expensive and complex access mechanisms, such as pullout networks (Mozer, 1984) or clause-spaces (Touretzky & Hinton, 1985).

• Third, they can only encode structures composed of a fixed tiny set of representational elements, (i.e. like triples of 25 tokens), and can only represent a small number of these element-structures before spurious elements are introduced2. These representational spaces are, figuratively speaking, like a “prairie” covered in short bushes of only a few species.

• Finally, they utilize only binary codes over a large set of units.

The compositional distributed representations devised by the technique to be described below demonstrate somewhat opposing, and, I believe, better properties:

• Less human work in design by letting a machine do the work,

• Simple and deterministic access mechanisms,

• A more flexible notion of capacity in a “tropical” representational space: a potentially very large number of primitive species, which combine into tall, but sparse structures.

• Finally, the utilization of analog encodings.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. First, I describe the strategy for learning to represent stacks and trees, which involves the co-evolution of the training environment along with the access mechanisms and distributed representations. Second, I allude to several experiments using this strategy, and provide the details of an experiment in developing representations for binary syntactic trees. And, finally, some crucial issues are discussed.

RECURSIVE AUTO-ASSOCIATIVE MEMORY

Learning To Be A Stack

Consider a variable-depth stack of L-bit items. For a particular application, both the set of items (i.e. a subset of the 2L patterns) and the order in which they are pushed and popped are much more constrained than, say, all possible sequences of N such patterns, of which there are 2LN . Given this fact, it should be possible to build a stack with less than LN units (as in a shift-register approach) but more than L units with less than N bits of analog resolution, as in an approach using fractional encodings such as the one I used in the construction of a “neuring machine” (Pollack, 1987a).

The problem is finding such a stack for a particular application.

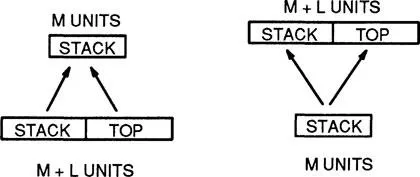

Proposed inverse stack mechanisms in single-layered feedforward networks.

Consider representing a stack in a activity vector of M bounded analog values, where M>L. Pushing a L-bit vector onto the stack is essentially a function that would have L+M inputs, for the new item to push plus the current value of the stack, and M outputs, for the new value of the stack. Popping the stack is a function that would have M input units, for the current value of the stack, and L+M output units, for the top item plus the representation for the remaining stack. Potential mechanisms in the form of single-layered networks are shown in figure 1. The operation performed by a single layer is a vector-by-matrix multiplication and then a non-linear scaling of the output vector to between 0 and 1 by a logistic function.

All we need for a stack mechanism then, are these two functions plus a distinguished M-vector of numbers, ε, the empty vector. To push elements onto the stack, simply encode the element plus the current stack; to pop the stack, decode the stack into the top element and the former stack. Note that this is a recursive definition, where previously encoded stacks are used in further encodings. The problem is that it is not at all clear how to design these functions, which involve some magical way to recursively encode L+M numbers into M numbers while preserving enough information to consistently decode the L +M numbers back.

One clue for how to do this comes from the Encoder Problem (Ackley, Hinton, & Sejnowski, 1985), where a sparse set of fixed-width patterns are encoded i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- The Place of Cognitive Architectures in a Rational Analysis

- Transitions in Strategy Choices

- VITAL, A Connectionist Parser

- Applying Contextual Constraints in Sentence Comprehension

- Recursive Auto-Associative Memory: Devising Compositional Distributed Representations

- Experiments with Sequential Associative Memories

- Representing Part-Whole Hierarchies in Connectionist Networks

- Using Rules and Task Division to Augment Connectionist Learning

- Analyzing a Connectionist Model as a System of Soft Rules

- How to Summarize Text (and Represent it too)

- On-Line Processing of a Procedural Text

- Understanding Stories in their Social Context

- Context Effects in the Comprehension of Idioms

- Action Planning: Routine Computing Tasks

- Using Conversation MOPs to Integrate Intention and Convention in Natural Language Processing

- A Theory of Simplicity

- Basic Levels in Hierarchically Structured Categories

- Flexible Natural Language Processing and Roschian Category Theory

- The Induction of Mental Structures While Learning to Use Symbolic Systems

- Transitory Stages in the Development of Medical Expertise: The “Intermediate Effect” in Clinical Case Representation Studies

- Integrating Marker Passing and Connectionism for Handling Conceptual and Structural Ambiguities

- Learning Subgoals and Methods for Solving Problems

- Opportunistic Use of Schemata for Medical Diagnosis

- Integrating Case-Based and Causal Reasoning

- Modeling Software Design Within a Problem-Space Architecture

- Modeling Human Syllogistic Reasoning in Soar

- Integrated Commonsense and Theoretical Mental Models in Physics Problem Solving

- A Connectionist Model of Selective Attention in Visual Perception

- How Near is too Far? Talking About Visual Images

- An Adaptive Model for Viewpoint - Invariant Object Recognition

- Spatial Reasoning Using Sinusoidal Oscillations

- An Unsupervised PDP Learning Model for Action Planning

- Representation and Recognition of Biological Motion

- When half right is not half bad: Hypothesis testing under conditions of uncertainty and complexity

- A Theory of Scientific Problem Solving

- Empirical Analyses and Connectionist Modeling of Real-Time Human Image Understanding

- Learning to Represent and Understand Locative Prepositional Phrases

- A Computational Model of Syntactic Ambiguity as a Lexical Process

- A Parallel Model for Adult Sentence Processing

- Parsing Metacommunication in Natural Language Dialogue to Understand Indirect Requests

- Interpretation of Quantifier Scope Ambiguities

- Multiple Simultaneous Interpretations of Ambiguous Sentences

- The Role of Analogy in a Theory of Problem Solving

- The Architecture of Children’s Physics Knowledge: A Problem-Solving Perspective

- Hierarchical Problem Solving as a Means of Promoting Expertise

- Collaborative Cognition

- Explorations in Understanding How Physical Systems Work

- Instructional Strategies for a Coached Practice Environment

- Creatures of Habit: A Computational System to Enhance and Illuminate the Development of Scientific Thinking

- Propositional Attitudes, Commonsense Reasoning and Metaphor

- A Process-Oriented, Intensional Model of Knowledge and Belief

- Subcognitive Probing: Hard Questions for the Turing Test

- The Pragmatics of Expertise in Medicine

- Cognitive Flexibility Theory: Advanced Knowledge Acquisition in Ill-Structured Domains

- A Hybrid Connectionist/Production System Interpretation of Age Differences in Perceptual Learning

- Language Experience and Prose Processing in Adulthood

- Effects of Age and Skill on Domain-Specific Visual Search

- Patching Up Old Plans

- Systematicity as a Selection Constraint in Analogical Mapping

- Abstraction Processes During Concept Learning: A Structural View

- Explanatory Coherence and Belief Revision in Naive Physics

- Access and Use of Previous Solutions in a Problem Solving Situation

- The Use of Explanations for Completing and Correcting Causal Models

- Varieties of Learning from Problem Solving Experience

- The Process of Learning LISP

- Interactive Medical Problem Solving in the Context of the Clinical Interview: The Nature of Expertise

- A Dynamical Theory of the Power-Law of Learning in Problem-Solving

- Assessing the Structure of Knowledge in a Procedural Domain

- Improvement in Medical Knowledge Unrelated to Stable Knowledge

- Sequential Connectionist Networks for Answering Simple Questions about a Microworld

- The Usefulness of the Script Concept for Characterizing Dream Reports

- The Right of Free Association: Relative-Position Encoding for Connectionist Data Structures

- Unsupervised Learning of Correlational Structure

- On the Application of Medical Basic Science Knowledge in Clinical Reasoning: Implications for Structural Knowledge Differences Between Experts and Novices

- Similarity-Based and Explanation-Based Learning of Explanatory and Nonexplanatory Information

- Causal Reasoning about Complex Physiological Mechanisms by Novices

- A Comparison of Context Effects for Typicality and Category Membership Ratings

- Naive Materialistic Belief: An Underlying Epistemological Commitment

- Writing Expertise and Second Language Proficiency: Algorithms and Implementations?

- The Minimal Chain Principle: A Cross Linguistic Study of Syntactic Parsing Strategies

- Multiple Character Recognition - A Simulation Model

- NETZSPRECH - Another Case for Distributed ‘Rule’ Systems

- Intuitive Notions of Light and Learning About Light

- Signalling Importance in Spoken Narratives: The Cataphoric Use of the Indefinit THIS

- Planning and Implementation Errors in Algorithm Design

- Conceptual Slippage and Analogy-Making: A Report on the Copycat Project

- Direct Inferences in a Connectionist Knowledge Structure

- Problem Solving is what you do when you don’t know what to do

- Cirrus: Inducing Subject Models from Protocol Data

- Three Kinds of Concepts?

- Constructing Coherent Text Using Rhetorical Relations

- Defeasibility in Concept Combination: A Critical Approach

- The Comprehension of Architectural Plans By Expert and Sub-Expert Architects

- Processing Aspectual Semantics

- Gain Variation in Recurrent Error Propagation Networks

- Conjoint Syntactic and Semantic Context Effects: Tasks and Representations

- Generalization by Humans and Multi-Layer Adaptive Networks

- Pattern-Based Parsing Word-Sense Disambiguation

- Multiple Theories in Scientific Discovery

- Text Comprehension: Macrostructure and Frame

- The Structure of Social Mind: Empirical Patterns of Large-scale Knowledge Organization

- A Model of Meter Perception in Music

- Acquiring Computer Skills by Exploration versus Demonstration

- A Hybrid Model for Controlling Retrieval of Episodes

- The Role of Mapping in Analogical Transfer

- Spatial Attention and Subitizing: An Investigation of the FINST Hypothesis

- A Computational Model of Reactive Depression

- Reasoning by Rule or Model ?