![]()

Chapter 1

The Role of African-American Social Workers in Social Policy

Tricia B. Bent-Goodley

Policy practice can be defined as “efforts to change policies in legislative, agency and community settings, whether by establishing new policies, improving existing ones, or defeating the policy initiatives of other people” (Jansson, 1999, p. 10). The Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (EPAS) (2001) has reinforced the need for a greater emphasis on policy practice in educating social work students. The value of policy practice has been emphasized as significant for all social workers in impacting key social work issues (Figueira-McDonough, 1993; Haynes and Mickelson, 2000; Jansson, 1999; Schneider and Lester, 2001). Social workers have been encouraged to impact social policy and use their unique role to lobby for social welfare policy that meets the needs of constituents (Domanski, 1998; Hoechstetter, 1996; Hoechstetter, 2001; Schneider and Netting, 1999; Stuart, 1999). Numerous publications provide specific techniques of political intervention, advocacy, and strategies to increase policy practice skill (Dear and Patti, 1981; Fisher, 1995; Jansson, 1999; Mahaffey and Hanks, 1982; Powell and Causby, 1994; Roberts-DeGennaro, 1986; Rocha, 2000; Schneider and Lester, 2001; Wolk et al., 1996). Much of the emphasis has been placed on increasing the motivation and desire of social workers to want to impact social change through enhanced political participation (Domanski, 1998; Ezell, 1993), yet it is unclear how African-American social workers perceive themselves within policy practice. As African Americans are disproportionately affected by social policy issues, such as child welfare (Brown and Bailey-Etta, 1997; Everett, Chipungu, and Leashore, 1997), it is important to assess their participation in social change through policy practice.

The role of African-American social welfare pioneers in policy practice has been illustrated (Bent-Goodley, 2001; Carlton-LaNey, 1994, 2001; Carlton-LaNey and Burwell, 1996) through activities such as lobbying, engaging in coalition building, developing relationships with policymakers, analyzing policy, organizing letter writing campaigns, and running for public office. Policy practice of contemporary African-American social workers has not been well documented. The purpose of this chapter is to report the findings of an exploratory study that examines the political participation and policy analysis criteria of African-American social workers.

Literature Review

Political participation can be defined as one’s desire “to influence the structure of government, the selection of government authorities, or the policies of government” (Conway, 1991, p. 3). Previous studies on the political participation of social workers have either had small samples of African Americans or have provided limited attention and documentation of data analyzed according to race (Ezell, 1993; Hamilton and Fauri, 2001; Salcido and Seck, 1992). In addition, the study will examine the policy analysis criteria for African-American social workers. Policy analysis is defined as the development of “policy alternatives to address [policy issues], then select a preferred alternative in the course of policy deliberations” (Jansson, 2000, p. 41). The means by which African-American social workers evaluate social policies is also limited in the literature. This study seeks to build on both determining African-American social workers’ political participation and understanding the ways in which African-American social workers assess policy.

Wolk’s (1981) study of the political participation of social workers found that older social workers, those in macro positions, social workers with higher incomes, and those practicing in the profession longer were more likely to engage in political activity. Although he focused on those statistically significant findings, he also shared non-statistically significant results that indicated a greater level of political participation by women than men, African Americans than whites, and social workers with doctorates versus those without doctorates. His findings did not illustrate the techniques of African-American social workers in impacting the policy process but it did acknowledge their higher level of political participation.

Salcido and Seck (1992) examined the political participation of fifty-two National Association of Social Work (NASW) chapters across the country. The study found that social workers were more likely to engage in writing letters, phoning officials, and lobbying legislators versus working with interest groups, campaigning, or organizing protest rallies, regarded as more conflict-oriented activities. Salcido and Seck further noted that “involvement in protest activities and voter registration is minimal” and that “these activities can be used to empower the poor, [people of color], and social service clients” (1992, p. 564). This study did not illustrate an examination of political participation according to race; however, it importantly noted that social workers are more likely to engage in political activities that are less confrontational, less rooted in grassroot communities, and less likely to be on behalf of and working with the oppressed.

Ezell (1993) examined the political participation of 353 members of the NASW Washington State Chapter (n = 311) and graduates of the University of Washington School of Social Work (n = 42). He found that “Black social workers [were] the most active; NASW members [were] more active than non-members and macro practitioners [were] more involved than micro practitioners” (p. 86). No statistical significance according to gender was found, although women appeared to be more politically active than men. It was the sample’s previous volunteer experience that predicated the likelihood of greater political activity, although social workers were likely to engage in client advocacy more regularly than other types of influence. The study also found that social workers were more likely to engage in letter writing, attending meetings, and discussing politics among individual cohorts than campaigning, making contributions, and testifying. Finally, Ezell emphasizes the need to further expose social work students to political practice and to create a better understanding of how social work values and ethics can be integrated with the policy process.

Hamilton and Fauri (2001) reported on a survey that measured the political activity of 242 social workers in New York State. The findings confirmed no difference in political activity based on demographics such as income, upbringing, or age. However, they did find that those social workers most likely to engage in political activity were recruited to participate by an organization or were individuals already interested in political affairs.

These studies provide an important understanding of the political participation of social workers; however, the contributions and techniques of African-American social workers are not clearly delineated. As a result, this study built on the previous literature by enhancing our understanding of African-American social workers’ role in the policy process.

Schiele (2000) promotes an African-centered approach to policy that includes race specific policies focused on improving the socio-political and economic standing of people of African ancestry. He emphasizes that policy analysis should be “understood more holistically and circularly in a manner that synthesizes seemingly contradictory and unrelated components” (p. 172). Understanding the strengths and self-help tradition of communities of African ancestry and including them in the policy decision-making process is a key aspect to analyzing social policy from an African-centered perspective. He further emphasizes the need to build on the collective standing of the community as opposed to using policy analysis to further oppress individuals and communities. Schiele provides a key understanding as to how one can use the policy process to empower people of African ancestry. This chapter will build on his work by identifying the means by which African-American social workers evaluate social policy.

Methodology

This study builds on the previous literature by focusing on the political participation of African-American social workers and their criteria for assessing social policy. A pilot study was conducted before the survey was disseminated to assess its reliability. A focus group was conducted with five African-American policy experts, including two policy practitioners on the state and federal levels respectively and three social policy scholars. The focus was to provide feedback on the questionnaire. Minor changes were made to the questionnaire as a result of the feedback.

Participants and Procedure

A purposive sample of 116 African-American social workers self-selected to participate in the survey utilizing a ten-item, closed-ended and seven-item, open-ended questionnaire. The study’s participants were attending a policy workshop at the 2000 National Association of Black Social Workers (NABSW) Conference. There was a pool of 132 social workers at the session, indicating an 88 percent response rate.

The questionnaire consisted of three sections: the first section obtained demographic information, the second section obtained information regarding political participation and levels of influence, and the third section contained information on policy analysis criteria. To determine the primary methods of political activities and the extent of political participation, the respondents were asked to specify their methods of participation in ten political activities over the past two years. They also were asked to indicate additional methods of influence not listed. This process resulted in one additional category: voter registration and education or grassroots organizing. Level of political activity was gauged through self-identification on a scale of no or little participation as nonactive participation, occasional participation as active, and frequent participation as very active (Ezell, 1993).

The sample was predominantly composed of women, as 81 percent of respondents were female (n = 94). The age range of respondents was 23 years (n = 5) to 87 years (n = 2), a mean age of 42 years and a median age of 42.5 years. Thirty-four percent identified as direct service practitioners, 24 percent as macro practitioners, and 38 percent identified as using a combination of both areas of practice. Macro practitioners included supervisors, administrators, policy analysts, entrepreneurs, and community organizers. Ninety-four percent of respondents possessed a MSW degree, with 13 percent (n = 15) of respondents indicating a doctorate in social work.

Findings

One quarter of respondents classified their political participation as nonactive, 55 percent as active, and 16 percent as very active. Respondents indicated that their greatest influence took place on the local level (56 percent, n = 65). The next greater area of influence took place on the state level (17 percent, n = 20), with the smallest amount of influence noted on the federal level (5.2 percent, n = 6).

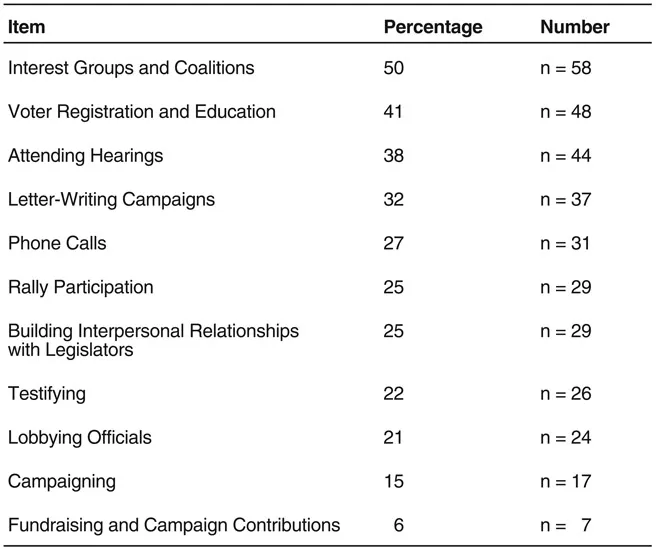

Table 1.1 reveals the distribution of political activity among the respondents. Fifty percent of the respondents indicated working with interest groups to influence policy. Over one-third of respondents indicated the use of three types of political activities: voter registration and grassroots organizing (41 percent, n = 48), attending hearings (38 percent, n = 44), and engaging in letter writing campaigns (32 percent, n = 37).

TABLE 1.1. Itemized Responses to Political Activity Methods of Influence

One quarter or slightly less of respondents indicated the political activities of five methods: phoning officials (27 percent, n = 31), attending protest rallies (25 percent, n = 29), building interpersonal relationships with legislators (25 percent, n = 29), testifying (22 percent, n = 25), and lobbying officials (21 percent, n = 24). The lowest scores of political activities included participating in campaign activities (15 percent, n = 17) and contributing funds to campaigns (6 perc...