![]()

Chapter One

Keeping it in the family: women and aristocratic memory, 700-1200

MATTHEW INNES

Around the year 1000, the English nobleman Ealdorman Æthelweard addressed a Latin translation of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to his distant German cousin Abbess Matilda of Essen. Commenting in his letter of dedication that the Chronicle contained ‘so many wars and slayings of men’, he went on to concentrate on the family past he shared with Matilda, delineating their common ancestry. Such knowledge of the family past, he wrote, was possible ‘so far as our memory provides proof and our parents taught us’.1 If we understand memory not so much as an act of personal recollection but as a process of social commemoration in which information is transmitted over time and space, then Æthelweard was describing its mechanisms within the family, to be compared with the written account of kings and battles in the Chronicle. Æthelweard’s family memory was taught orally by parents and committed to human memory without the use of writing. These mechanisms of remembering within the family are the subject of this chapter. Building on the work of Patrick Geary on medieval remembering, Janet Nelson on women and historical writing, and Elisabeth van Houts on gender and memory, it suggests that the transmission of family memory was a gendered role.2 Remembering the past was linked to female roles such as care for the dead, prayer for the salvation of the souls of kin, and child rearing. It was also a process that worked without written narratives. These mechanisms, it will be argued, were consciously chosen as they allowed aristocratic families to use the past to legitimate their present power.

Dhuoda: motherhood, prayer and the organisation of family memory

The work of one particularly articulate woman near the beginning of the period under review vividly demonstrates the role of women in the transmission of family memory. The spiritual Manual produced by the Carolingian noblewoman Dhuoda for her eldest son, William, was written between 841 and 843. Dhuoda’s husband, Bernard, was one of the most powerful men in Europe; he had interests and offices in southern France and the Spanish March, and was a central actor in the political conflicts of the 830s and 840s. William had been born some time after his parents’ marriage in 824, and in 841 was placed at the court of the young king Charles the Bald (840–77) as a means of ensuring Bernard’s continued loyalty (although such a finishing at court was customary for the children of the powerful).3

Dhuoda presented her Manual as a written substitute for her physical presence; writing down moral advice was a way of continuing the bond between mother and son, offering spiritual guidance that could not be given by word of mouth.4 It is one of a series of ninth-century tracts of moral instruction, but a uniquely interesting work as it was written by a laywoman rather than a churchman. In Dhuoda’s eyes, life at court, whilst it offered many opportunities, also led William into political and moral danger. Dhuoda, indeed, emphasised her own involvement in secular affairs, highlighting her marriage at court and her later work in support of her husband. Was she reminding her audience of the knowledge of the world that gave her advice real authority? In the past, Dhuoda has been portrayed as genuinely pious but relatively artless, simply repeating the lessons of the Carolingian church. Views are changing, however, and Dhuoda is emerging as an author of no little skill and originality.5

Dhuoda instructed William in his obligations to the three concentric social groups of which he was a member; in meeting these obligations, William created his social identity.6 First, his membership of the community of all Christians was articulated by regular participation in the public rituals of Christian worship, especially regular prayer for all Christians, dead and alive. Secondly, William’s relations with his peers within the political élite led to moral obligations towards his leaders and comrades, again cemented by specific duties of prayer, for William as their fellow and follower was to take personal care for their souls. Thirdly and finally, Dhuoda, as William’s mother, took special responsibility for ensuring that he offered up prayer for his kin: ‘I shall die, and I entreat you to pray for all the dead, but especially those from whom you trace your origin in the world.’7

Dhuoda’s description of William’s obligations towards his kin has been noted in several recent discussions of family memory,8 but a close reading can bring fresh insight. Dhuoda stressed the practicalities of the inheritance of power as the matrix on to which memory mapped:

Pray for your father’s relatives [parentes], who have bequeathed him their possessions in lawful inheritance. You will find who they were, and their names, written down in the chapters towards the end of this little book. Although the Scripture says ‘A stranger luxuriates in another’s goods’, it is not strangers who possess this legacy. As I said earlier, it is in the charge of your lord and father, Bernard.

To the extent that those former owners have left their property in legacy, pray for them. And pray that you, as one of the living, may enjoy the property during a long and happy lifetime. For I think that if you conduct yourself towards God with worthy submission, the loving One will for this reason raise up fragile honours [dignitates] for your benefit.

If through the clemency of almighty God, your father decides in advance that you shall receive a portion, pray then with all your strength for the increasing heavenly recompense to the souls of those who once held all these. Circumstances do not allow your father to do so, since he has many urgent duties [occupationes]. But you, insofar as you have the strength and opportunity, pray for their souls.9

In other words, the inheritance of property by the living from the dead was reciprocated through counter-gifts of prayer by the living for the dead. Death was a fundamental shock to the social order, necessitating the redistribution of the power of the deceased. The exchange of prayers for inheritance eased this renegotiation, and bound the living members of a family to their dead ancestors, whose souls were aided and lives commemorated in recognition of their legacy.10

Dhuoda allows us a glimpse of the workings of this mechanism of social reproduction:

Other members of your lineage [genealogia] are still living in this world, thanks to God: they depend wholly on He who created them . . . When a member of your kin [stirps] passes on, which happens only through God’s power and on the day he ordains . . . I ask you if you survive him to have his names inscribed among the names of those persons I have listed above, and to pray for him.11

Dhuoda herself was fervently concerned about her son’s responsibility to ensure her own commemoration through salvation-aiding prayer after her death: ‘It is true that I do not deserve to be counted among those whom I have numbered above. All the same, I ask you to pray ceaselessly for me, along with countless others, for the healing of my soul, with an affection that is countable towards me.’ William was asked to practise not only vigil and prayer but also alms giving; he and his brother were to take particular care to organise the offering of the mass for Dhuoda’s soul.12 Dhuoda went on to give William an epitaph to inscribe on her tomb, so that those who saw it would be able to pray on her behalf. She finally enjoined William to ensure that ‘when I myself have ended my days, be sure that you have my name inscribed among the dead’.13

We can see the connections between commemoration and inheritance in William’s obligations towards his dead paternal uncle, Theodoric. Theodoric had stood godfather to William at his baptism, and had invested his godson with arms when he entered his adult life. He had enjoyed a special role as William’s helper and guide (nutritor and amator). William was to repay this care by praying assiduously for Theodoric’s soul:

Pray often for Theodoric, especially in the company of other people, at nocturns, matins, vespers and all the other canonical hours, at all times and places. Do this as often as you can, in case he may have acted unjustly and failed to do penance for his eternal soul. Do this as much as you can, especially among good people, and through the prayers of holy priests. See that alms are distributed to the poor on his behalf and that the sacrifice of the mass is offered to the lord for him.14

Dhuoda’s stress on the debt owed by William to Theodoric was pointed. When William was sent by his father to enter into the service of Charles the Bald, just before Dhuoda began writing, he had received honores – offices and lands held from the king – in Burgundy.15 These honores had been Theodoric’s; William’s special relationship to Theodoric informed his claim on them. Indeed, Dhuoda’s comments on Theodoric’s legacy were consciously open ended, designed to further William’s claim: ‘when he left you in this world as if you were his little firstborn son, he bequeathed everything [cuncta] to our lord and master, so that you might benefit in every way’.16 Remembering this ancestor not only prolonged a special personal relationship beyond the grave, but also legitimated newly won power and underpinned a political strategy.

Dhuoda was explicit about these functions of family memory; if William took proper care of his ancestors, she hoped, he would not only hold their property, but also be raised up to high office (dignitates) through God’s backing.17 Family memory was not something that she merely tended; it was pruned and shaped to meet current needs. Dhuoda inscribed the names of those dead ancestors for whom William was to offer special prayer: ‘Here

Table 1.1: William’s obligations to his kin, showing relations for whom he was to pray

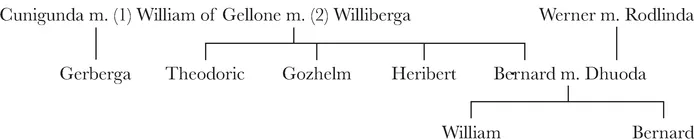

briefly you will find the names of the various persons whom I have omitted earlier [in book 8, chapter 14, where Dhuoda had instructed William to pray for his relatives]. They are William, Cunigunda, Gerberga, Williberga, Theodoric, Gozhelm, Werner and Rodlinda.’18

This list was not a simple reflection of biological realities, but involved a series of choices to include and exclude. The principle of selection was clearly stated by Dhuoda: the extent that kin had bequeathed property to William and his father. Charters – legal deeds recording the transfer of land, usually to the church – reveal family structures similar to those recorded by Dhuoda, rooted in the inheritance of property and mutual obligations most visible to us in prayer and pious gifts. These relatively compact kinship groupings, not the large clans imagined by earlier historians, are emerging as the basic building blocks of aristocratic society in our period. They seem to have enjoyed a considerable fluidity, in that groups of relatives could coalesce electively around powerful figures, and were re-formed from generation to generation. Hence Dhuoda’s own ancestors were all but ignored in her advice to William, who was to commemorate only his maternal grandmother and grandfather, Werner and Rodlinda.19 The kinship structures of the Carolingian aristocracy were bilateral, and maternal kin were potentially as significant as paternal; Dhuoda, indeed, on occasion emphasised the bilateral nature of kinship.20 But Dhuoda’s family was based in the distant Moselle valley, in a different Carolingian kingdom, where Bernard’s political opponents ruled the roost. Whilst William was to remember his mother and her parents, more distant maternal kin were forgotten; their backing, their lands and offices, were scarcely useful to William, whose political future lay in southern France, in the claims and contacts built up by his father’s kin. Family memory, that is, used the past to articulate shared concerns with present allies.

The fragments of information that survive about the ancestors commemorated by William suggest that Dhuoda’s list contained an implicit political manifesto. She wrote:

I think now of those whose stories I have heard and read, and I have seen members of my family, and yours, my son, whom I have known. Once they cut a powerful figure in the world, and then they were no more. They are perhaps with God because of their noble merits, but they are not physically present on earth.21

Here is a hint of the oral transmission of stories about ancestors that fleshed out the bare bones of the names of the family dead. Indeed, it is possible to identify the family members of whom Dhuoda was thinking. Amongst the ancestors for whom William was to pray were his uncle Gozhelm and his ...