eBook - ePub

Plantations, Proletarians and Peasants in Colonial Asia

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Plantations, Proletarians and Peasants in Colonial Asia

About this book

This volume originated in a conference on 'Capitalist Plantations in Colonial Asia', held at the Centre for Asian Studies of the University of Amsterdam and Free University of Amsterdam in September 1990. The contributions to this collection focus on the production of rubber, sugar, tea, and several less strategic plantation crops, in colonial Indochina, Java, Malaya, the Philippines, India, Ceylon, Mauritius and Fiji (although geographically anomalous, both the latter are included because of the centrality to their sugar plantations of indentured labour from India).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Plantations, Proletarians and Peasants in Colonial Asia by Henry Berstein,Tom Brass,E.Valentine Daniel,H. Berstein,T. Brass,E.V. Daniel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Introduction: Proletarianisation and Deproletarianisation on the Colonial Plantation

TOM BRASS and HENRY BERNSTEIN

I

Introduction

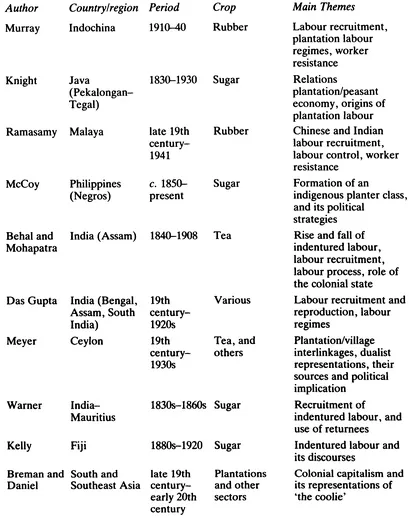

The contributions to this collection focus on the production of rubber, sugar, tea, and several less strategic plantation crops, in colonial Indochina, Java, Malaya, the Philippines, India, Ceylon, Mauritius and Fiji (although geographically anomalous, both the latter are included because of the centrality to their sugar plantations of indentured labour from India). The country or region, period, crop, and principal themes covered in each article are summarised in Table 1, which indicates that the major concerns of the authors are the origins and recruitment of plantation labour, the labour processes into which the plantation workforce was deployed, and the labour regimes governing this. Several contributions also address the ideological representation of the colonial 'coolie' (Kelly, Breman and Daniel) and the colonial plantation as alien 'enclave' (Meyer), while McCoy traces the exceptional formation and development of an indigenous planter class which gave 'Philippines plantations a depth of social and political penetration not found elsewhere in tropical Asia'.

What is missing from this collection, however, are similarly detailed and considered accounts of the forms and effects of workers' struggles on and against plantations, despite the useful glimpses of 'resistance' provided by Murray, Ramasamy, McCoy, Behal and Mohapatra, and Kelly. Accordingly, the importance of different forms of class struggle over the commodification, decommodification, and recommodification of labour power on the colonial plantation is a central theme in our theoretical discussion below.

Tom Brass is at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, University of Cambridge, Free School Lane, Cambridge CB2 3RQ, UK, and Henry Bernstein is at the Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9QS, UK.

TABLE 1

A further point of note concerning the various contributions is the period they address, from about the last third of the nineteenth century through the capitalist depression of the 1930s to the beginning of the Second World War. While recognising the salient legacy of earlier colonial plantations, both the slave plantations of the Americas and the earlier nineteenth-century plantations in Asia (Knight on Java, Behal and Mohapatra on Assam, Das Gupta on Bengal, Meyer on Ceylon), what is the significance of the 1870-1940 period? First, it was the apogee of European colonialism in Asia (and Africa), and, second, its onset coincides with the beginning of imperialism in the sense designated by Lenin: the 'highest stage of capitalism' marked by the transformation of competitive into monopoly capital, the hegemonic role of finance capital, and the internationalisation of capital driven by the need for super-profits. Again, several contributors (Murray, McCoy, Behal and Mohapatra) provide glimpses of the effects of the new imperialist world economy, in terms of the concentration and organisation of plantation capital, the pressures of overproduction and price fluctuations on the world market, and how these were transmitted to the plantation labour process in the form of workforce restructuring and technical change.

For Lenin, of course, the colonial expansion of the late nineteenth century, above all in Africa and parts of Southeast Asia, was an integral part of the emergence of capitalist imperialism, which, however, is not coterminous with nor reducible to colonial rule, as Lenin [1964: 263-4] illustrated in the cases of Argentina (post-colonial) and Portugal (itself a minor colonial power in Africa but dominated by British imperialism). The analysis of imperialism reminds us both that the great expansion of plantation export agriculture in the late nineteenth century, and the unfree labour regimes it employed, was not restricted to colonial territories, and that unfree labour was also central to sectors other than plantation agriculture. On the first point, for example, Latin America's massive export boom from the 1870s manifested 'a virtually unique combination in the nineteenth century of political independence and primary commodity led incorporation into the international capitalist economy' [Archetti et al., 1987: xvi], fuelled by a range of forms of indentured, bonded and other unfree labour [Brass, 1990a], On the second point, for example, from the late nineteenth century onwards capital in Southern Africa exhibited an almost insatiable demand for labour for mining as well as farming (see, inter alia, van Onselen [1976]; Levy [1982]; First [1983]; Kimble [1985]; Miles [1987]). In fact, some of the mechanisms and practices of unfree labour in South Africa to this day provide useful points of comparison with those described in this volume in the context of plantations in colonial Asia.

To summarise the three major features of the period of global capitalism with which the contributions to this volume are centrally concerned. First, the formation of a world market shaped by the needs of increasingly rapid capitalist industrialisation in the course of the nineteenth century generated an accelerated demand for agricultural commodities of all kinds, with a particular burst of expansion from the 1870s onwards (and despite the depression of 1873-96, which Lenin identified as the catalytic moment in the emergence of imperialism). As well as a new scale of international demand for grains, sugar, tea, coffee, tobacco and bananas, there was an even greater expansion of demand for crops associated with industrial processing and manufacturing, such as vegetable oils, cotton, sisal, jute and rubber, the last an exemplary raw material of the 'Second Industrial Revolution' of the late nineteenth century (Murray in this volume; see also Barraclough [1964: Ch. 2] and Hobsbawm [1987: Ch. 3]). Second, the movement of these commodities in ever increasing quantitites was made possible both by technical changes that dramatically lowered the costs of long distance bulk transport, and by the opening of strategic new transport routes.

Third, how was the supply of these commodities ensured? In his outline of plantation agriculture, Courtenay [1965: Ch. 3] speaks of the 'rise of the industrial plantation' in the nineteenth century, and notes in particular the pace of its expansion from around the 1870s. The 'industrial plantation' replaced previous types in the 'traditional' areas in the Americas (a transformation Courtenay associates with the change in the Caribbean and Brazil from chattel slavery to indenture and other forms of contract labour), and in Asia was connected both with change in and massive expansion of existing plantation areas such as Java (Knight), Negros (McCoy), Assam (Behal and Mohapatra) and Ceylon (Meyer), and with the rapid development of new plantion 'frontier' zones in Indochina (Murray), Malaya (Sundaram [1986: Ch. 7]), and Sumatra (Stoler [1985], Breman [1989]).

What makes the 'industrial plantation' in the epoch of imperialism distinctive is the connection between its organisation of production (labour processes, technologies, management structures and imperatives), its character as (part of) corporate capitalist enterprise, and the new, more highly integrated, conditions of its world market location, involving linkages with finance capital, shipping, industrial processing and manufacturing - aspects of that late nineteenth century development aptly described as a 'worldwide shift towards agribusiness' (Stoler [1985: 17]; see also Beckford [1972]). The 'industrial plantation' thus represented new forms of capital, and indeed a new form of capitalism (imperialism). Lenin's view that the dynamic of the internationalisation of capital is the pursuit of super-profits returns us, then, to questions concerning the conditions and mechanisms of the exploitation of labour, in the plantation, in other colonial capitalist sectors, and also (by implication) in the post-colonial imperialist periphery.

Given the continuing debate about the place of the plantation in the colonial economy, together with the latter's capitalist/non-capitalist nature, the most problematic issues concern the theorisation of the social relations of production structuring the plantation economy, and in particular their free/unfree nature.1 This in turn entails confronting two interrelated revisionist characterisations of the plantation workforce: in economic terms as effected by neo-classical theory, and (more insidiously) in what might be called 'culturalist' terms, as effected by moral economy, survival strategies and resistance theory. In their different ways, all these (re-) interpretations of the plantation system in general, and in particular its meaning for the workforce, involve either the denial or the dilution of its unfree element.

By contrast, here it is intended to examine the dynamic of freedom/ unfreedom as this informs the recruitment/reproduction of plantation labour, and its proletarian/peasant origins, together with the multiple trajectories/combinations which have been outcomes of class formation/struggle in this context (depeasantisation, peasantisation, prole tarianisation, deproletarianisation, reproletarianisation).2 As it structures the reproduction of different variants of labour-power employed on the plantation, class struggle is waged both from below (in the form of experiencing/attempting a process of becoming, in the case of the Caribbean a crucial development for a post-emancipation workforce composed of ex-slaves) and also from above (in the double form of conflict among the different components of capital over access to and control of labour-power, and by capital to displace/pre-empt the emergence of a specifically proletarian consciousness).

The Problematic of Free Wage Labour in Capitalism

The necessary starting point for a consideration of the trajectories followed by plantation labour is Marx's emphasis on the freedom of wage labour in the relationship between labour and capital, the social relation of production that constitutes the distinctive character of capitalism. As is well known, the designation of the freedom of wage labour has a double aspect: labouring subjects ('direct producers') are 'freed' from access to the means of production that secure their reproduction, and consequently they are (and must be) free to exchange their labour-power with capital for wages with which to purchase subsistence.3

Generally speaking, both aspects of wage labour capture the difference between capitalism and pre-capitalist modes of production. The first aspect signals the moment of dispossession of pre-capitalist producers, part of the process of primitive accumulation. Dispossession is the condition of the formation of a class of free wage labour which is the second aspect, or moment of proletarianisation. The contrast here is that, whereas in pre-capitalist modes of production labour is exploited by means of extra-economic compulsion, under capitalism proletarians are owners of the commodity labour-power which they exchange with capital under the 'dull compulsion of economic forces'.

Having outlined these familiar positions, it is useful to interrogate them a little further. First, with regard to the moment of dispossession, it is necessary to recognise that not all social subjects in all pre-capitalist formations necessarily had property or usufruct rights in land and/or other means of production, let alone that all pre-capitalist formations guaranteed the means of subsistence. Indeed, as several contributors to this volume show, strongly differentiated pre-capitalist formations in Asia contained landless labourers 'available' for recruitment by colonial capitalism.4 In short, dispossession of pre-capitalist producers was not always necessary to the (initial) formation of a class of capitalist wage labour.5

This brings us to the second, and more general, moment of proletarianisation, This too has an important double aspect, albeit often overlooked or confused, that is conveyed theoretically in the distinction between labour-power and labour, and more concretely in the difference between labour market and labour process. Labour-power is the capacity to work that is the property of workers (their mental and physical energies): the commodity they exchange with capital for wages. Labour is the use value of labour-power; the expenditure of the mental and physical energies of workers in a production process controlled by capitalists, the products of which are the property of the latter and not the former. Correspondingly, the labour market designates the site in which labour-power is exchanged, and the labour process the site in which labour is expl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction: Proletarianisation and Deproletarianisation on the Colonial Plantation

- 'White Gold' or 'White Blood'?: The Rubber Plantations of Colonial Indochina, 1910-40

- The Java Sugar Industry as a Capitalist Plantation: A Reappraisal

- Labour Control and Labour Resistance in the Plantations of Colonial Malaya

- Sugar Barons: Formation of a Native Planter Class in the Colonial Philippines

- 'Tea and Money versus Human Life': The Rise and Fall of the Indenture System in the Assam Tea Plantations 1840-1908

- Plantation Labour in Colonial India

- 'Enclave' Plantations, 'Hemmed-In' Villages and Dualistic Representations in Colonial Ceylon

- Strategies of Labour Mobilisation in Colonial India: The Recruitment of Indentured Workers for Mauritius

- 'Coolie' as a Labour Commodity: Race, Sex, and European Dignity in Colonial Fiji

- Conclusion: The Making of a Coolie

- Abstracts