![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

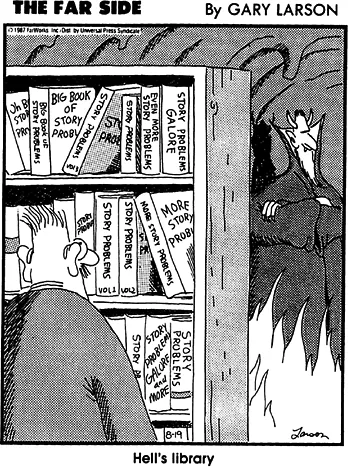

I often elicit an emotional reaction when I tell people that I do research on solving algebra word problems. Some people are quite good at doing this and enjoy the challenge. More typically, people moan. They never did very well at solving word problems, and may feel helpless when their children need assistance with their homework. Gary Larson’s cartoon (see Fig. 1.1) captures this typical reaction.

The purpose of this book is to try to bring together ideas from the fields of cognitive psychology, mathematics education, and educational technology to achieve a better theoretical and practical understanding of how students attempt to solve word problems. My perspective is that of a cognitive psychologist who does research on mathematical problem solving. Until recently, I had not paid much attention to curriculum reform in mathematics education, which is starting to find its way into classrooms across the country (Alper, Fendel, Fraser, & Resek, 1995; Heid & Zbiek, 1995; Kysh, 1995). But the current debate regarding the reform of mathematics education has brought these issues to the front pages of our newspapers. As newspaper articles continued to appear on this controversy between teaching basic skills and teaching concepts, I decided that research on mathematical problem solving would be of greater interest to me and my readers if I embedded it within the context of this ongoing debate. Therefore, I begin by giving a brief overview of the debate, which was stimulated by the publication of Curriculum and Evaluation Standards for School Mathematics (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics [NCTM], 1989).

The NCTM Standards

Unlike countries in which a national curriculum exists in mathematics (e.g., Japan, United Kingdom, China), the United States has no national curriculum. The Curriculum and Evaluation Standards for School Mathematics (NCTM, 1989) represents an attempt to develop such a vision at a national level. There were numerous motivating factors for establishing a set of standards that could be used to change the way mathematics is taught in elementary and secondary schools (Putnam, Lampert, & Peterson, 1990). Critics of the current curriculum pointed to test scores that showed American students lagged behind students in other industrialized countries. Business leaders claimed that the labor force in our information-oriented society needed more sophisticated mathematical skills, particularly the ability to communicate with mathematical systems and solve a variety of complex problems. Changes in the labor force had been brought about by advances in technology and information systems, but the learning and teaching of mathematics had not shifted correspondingly to meet these changes.

But the strongest push for a change came from mathematics educators who argued that current instruction focused too much on efficient computation and not enough on problem solving and mathematical understanding. Instruction should have a more conceptual orientation and less of a calculational orientation. Thompson, Philipp, Thompson, and Boyd (1994) expressed this view in the following way:

According to the NCTM, the curriculum should be broadened to place more emphasis on conceptual understanding and underrepresented topics in geometry, measurement, and statistics. In addition there should be greater emphasis on interacting with technology to facilitate calculations and graphing, as well as solving more difficult problems. These problems should include word problems with a variety of structures, everyday problems, and problems that take more than a few minutes to solve. Instruction should emphasize the acquisition of knowledge within the context of purposeful activity, rather than first learning computational skills for later application in solving problems. And finally, the nature of the classroom should shift away from students being passive recipients of mathematical knowledge to a classroom in which students are more actively engaged in acquiring knowledge.

According to the NCTM standards, the curriculum should therefore emphasize the following activities:

• The active involvement of students in constructing and applying mathematical ideas;

• Problem solving as a means as well as a goal of instruction;

• Effective questioning techniques that promote student interaction;

• The use of a variety of instructional formats (small groups, individual explorations, peer instruction, whole-class discussions, project work);

• The use of calculators and computers as tools for learning and doing mathematics;

• Student communication of mathematical ideas orally and in writing;

• The establishment and application of the interrelatedness of mathematical topics;

• The systematic maintenance of student learning, embedding review in the context of new topics and problem situations;

• The assessment of learning as an integral part of instruction.

The Backlash

My introduction to the controversial nature of these proposed changes in the curriculum occurred at the grass-roots level. Several months before I began writing this book there was a meeting of parents and educators at the middle school where our son was attending seventh grade. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss implementing a new mathematics curriculum in the San Diego Unified School District. The group opposing the curriculum change was led by a scientist at the Salk Institute in La Jolla. He was concerned that his children would not receive a firm foundation in mathematics if the new curriculum (called College Preparatory Mathematics, or CPM) was adopted. Many other parents had a similar concern. Their views are summarized in Box 1.1.

The group supporting curriculum change-the San Diego Unified School District-also came prepared with handouts. One titled Myths and Realities about CPM said that the course had been evaluated with over 10,000 students and revised three times before it was released for general use. It defended the NCTM standards and argued that students would spend time on the traditional content of algebra and geometry, but go beyond traditional content to develop higher order thinking skills. A San Diego teacher’s view that we need to go beyond the basics is expressed in Box 1.2.

This debate has continued at a local, state, and national level. An article in the November 11, 1996, issue of the Los Angeles Times discussed the battle being fought in the state of California as both sides fought for positions on a board that would establish state guidelines for mathematics instuction. A month earlier, the cover story of an issue of U.S. News & World Report (Toch & Daniel, 1996) was on fixing schools. The story contrasted two different approaches to improving education; one building on the traditional approach as advocated in the book The Schools We Need and Why

Mathematically Correct is a San Diego Based group of parents and community members concerned about math education in our schools. Similar groups have recently formed throughout the state.

Broad changes in mathematics education are appearing in San Diego public schools. The new programs, often called reform math, new-new math, or Whole math are being introduced at all grade levels in response to controversial state guidelines. Our initial concerns about these programs arose from exposure to a curriculum called CPM (College Preparatory Mathematics), currently being taught at Muirlands and Standley Middle Schools. Similar programs will soon be introduced from Kindergarten to high school geometry.

• Constructivism (“Discovery Learning”)—This approach reduces the amount of material covered

• Teachers are no longer information providers—Instead, they are group facilitators. Questions of the teacher from individual students are discouraged

• Emphasis on discussions and essays—Takes time away from word problems and computational skills

• Practice and drills are reduced—Basic skills are less likely to become “automatic”

• Group work, Group tests and Group Grades—Individual contemplation, performance and time for consolidation of math knowledge is reduced

• Extensive Use of Calculators—Children become calculator-dependent, even for simple arithmetic

Although parents are told that the changes are based on new guidelines, parents need to know that all programs based on these guidelines are essentially experimental—they lack research support. Parents also need to know that these new guidelines are controversial, have been the subject of criticism by the members of the State School Board and many others, and are now the subject of public hearings as required by law.

• Do not adopt radical changes, such as Whole Math and Whole Language, without clear, well-documented, compelling, quantitative data to support them.

• Require parental permission before students are enrolled in experiments to test the value of such programs.

• Give parents of children at all levels in all schools the right to choose a traditional math program.

Box 1.1. Viewpoint of the mathematically correct organization.

We Don’t Have Them (Hirsch, 1996), and one establishing progressive teaching methods as advocated in the book Horace’s Hope: What Works for the Ameri...