![]() Part I

Part I

History![]()

1

Early Behaviorism

Behaviorism was once the major force in American psychology. It participated in great advances in our understanding of reward and punishment, especially in animals. It drove powerful movements in education and social policy. As a self-identified movement, it is today a vigorous but isolated offshoot. But its main ideas have been absorbed into experimental psychology. A leading cognitive psychologist, writing on the centennial of B. F. Skinner’s birth, put it this way: “Behaviorism is alive and I am a behaviorist.”1

I will describe where behaviorism came from, how it dominated psychology during the early part of the twentieth century, and how philosophical flaws and concealed ideologies in the original formulation sidelined it—and left psychology prey to mentalism and naïve reductionism. I propose a new behaviorism that can restore coherence to psychology and achieve the scientific goals behaviorism originally set for itself.

Psychology has always had its critics, of course. But at a time when it occupies a substantial and secure place in university curricula, when organizations of psychologists have achieved serious political clout, and when the numbers of research papers in psychology have reached an all-time high—more than 50, 000 in 1999 by one count2 and several times that number in 2012—the number of critics has not diminished nor have their arguments been successfully refuted.3 The emperor is, if not unclothed, at least seriously embarrassed.

Many eminent psychologists, beginning with philosopher and proto-psychologist William James (Plate 1.1), have tried to sort out the divisions within psychology. James’s suggestion, before the advent of behaviorism, was to divide psychologists into “tough” and “tender minded.” He would have called behaviorists tough minded and many cognitive, clinical, and personality psychologists tender minded. James might also have mentioned the division between practice (clinical psychology) and basic research (experimental psychology), between “social-science” and “natural-science,” or between “structural” and “functional” approaches—not to mention the split between mentalists and realists. Drafters of multiple-choice tests should consult R. I. Watson’s (1971) list of eighteen psychological slices and dices for a full list.4 But the main division is still between those who think mind is the proper subject for psychology and those who plump for behavior.

Plate 1.1 William James (1842–1910), philosopher, pioneer psychologist, and promoter of the philosophy of pragmatism, at Harvard during the late 1890s. There were two James brothers. One wrote delicate convoluted prose; the writing of the other was vivid and direct. Surprisingly, it was the psychologist, William, who was the easy writer (e.g., his Principles of Psychology, 1890), and the novelist, Henry (e.g., The Golden Bowl), who was hard to follow.

The nineteenth-century ancestor of the mentalists is Gustav Fechner (1801– 1887), the “father” of psychophysics. Fechner was the co-discoverer of the Weber-Fechner law, which relates the variability of a sensory judgment to the magnitude of the physical stimulus.5 This is one of the few real laws in psychology. For very many sensory dimensions, variability of judgment, measured as standard deviation or “just-noticeable difference” (JND), is proportional to mean. For example, suppose that people are able to correctly detect that weights of 100 g and 105 g are different just 50% of the time—so the JND is 5%; then the Weber-Fechner relation says that they will also be able to tell the difference between 1, 000 g and 1, 050 g just 50% of the time.

The Weber-Fechner relation is a matter of fact. But Fechner went beyond fact to propose that there is a mental realm with concepts and measurements quite separate from biology and physics. He called his new domain psychophysics. Many contemporary cognitive psychologists agree with him.

On the other side are biological and physiological psychologists. Biological psychologists believe that the fact of Darwinian evolution means that the behavior of people and nonhuman animals has common roots and must therefore share important properties. Physiological psychologists—neuroscientists— believe that because behavior depends on the brain, and because the brain is made up of nerve cells, behavior can be understood through the study of nerve cells and their interactions.

Behaviorism is in the middle of the mental-biological/physiological division, neither mentalistic nor, at its core, physiological.6 Behaviorism denies mentalism but embraces evolutionary continuity. It also accepts the role of the brain, but behaviorists are happy to leave its study to neuroscientists. As we will see, behaviorists seek to make a science at a different level, the level of the whole organism.

Since its advent in the early part of the twentieth century, behaviorism has been a reference point for doctrinal debates in psychology. Until recently, many research papers in cognitive psychology either began or ended with a ritual paragraph of behaviorist bashing—pointing out how this or that version of behaviorism is completely unable to handle this or that experimental finding or property that “mind” must possess.7 Much cognitive theory is perfectly behavioristic, but the “cognitive” banner is flourished nevertheless. No cognitivist wants to be mistaken for a behaviorist!

The behaviorists, in their turn, often protect their turf by concocting a rigid and idiosyncratic jargon and insisting on conceptual and linguistic purity in their journals. Theories, if entertained at all, are required to meet stringent, not always well-defined and sometimes irrelevant criteria. The behaviorists have not always served their cause well.

Behaviorism has been on the retreat until very recently. In 1989 a leading neo-behaviorist (see Chapter 2 for more on these distinctions) could write,

I have … used a parliamentary metaphor to characterize the confrontation … between those who have taken a stimulus-response [S-R] behavioristic approach and those who favor a cognitive approach … and I like to point out that the S-R psychologists, who at one time formed the government, are now in the loyal opposition.8

In a critical comment on English biologist J. S. Kennedy’s behavioristically oriented book The New Anthropomorphism,9 one reviewer—a distinguished biologist—assumed that behaviorism is dead:

If anthropomorphism produces results that are, in the normal manner of science, valuable, it will be persisted with; if it does not, it will be abandoned. It was, after all abandoned once before. The only danger … is that scientists can be enduringly obstinate in their investigations of blind alleys. Just think how long behaviourism lasted in psychology.10

As recently as 1999, a philosopher blessed with the gift of prophecy could write, “Not till the 1980s was it finally proved beyond doubt that although a clockwork toy [i.e., computer] may emulate a worm or do a fair imitation of an ant, it could never match a pig or a chimpanzee.”11 Evidently all those artificial intelligence types toil in vain, and behavioristic attempts to reduce human behavior to mechanical laws are foredoomed to failure. And of course, this particular critic wrote before an IBM computer12 beat the champions on the television quiz show Jeopardy! On the other hand, to be fair, computers aren’t doing too well with worms and ants either (see comments on C. Elegans in Chapter 16). But computers cannot yet be counted out as tools for modeling animal behavior.

Behaviorism is frequently declared dead. But although services are held regularly, the corpse keeps creeping out of the coffin. A naïve observer might well conclude that vigorous attacks on an allegedly moribund movement are a sure sign that behaviorism is ready to resurrect.

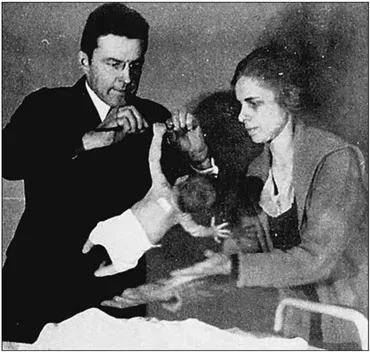

Plate 1.2 J. B. Watson and assistant (and wife-to-be) Rosalie Rayner studying grasping in a baby.

What is behaviorism, and how did it begin? The word was made famous by flamboyant Johns Hopkins psychologist John Broadus Watson (1878–1958, Plate 1.2). Watson, a South Carolina native, after some rambunctious teenage years, was a prodigious academic success until he had problems with his love life. Divorced in 1920 after his wife discovered he was having an affair with his research assistant Rosalie Rayner (a scandalous event in those days), Watson was fired from Johns Hopkins on account of the resulting publicity. Plus ça change—but nobody would notice nowadays, especially as Watson soon married Rosalie. The next year he joined the large advertising agency J. Walter Thompson, at a much-enhanced salary, where he very successfully followed the advertising version of the Star Trek motto: boldly creating needs where none existed before.13

His success in this new field was no accident. The major figures in the softer sciences have almost invariably been people with a gift for rhetoric, the art of verbal persuasion. They may have other skills (Skinner was a wonderful experimenter, for example), but their ability to found schools usually owes at least as much to their ability to persuade and organize as to their purely scientific talents.

Watson’s impact on psychology began with a nineteen-page article in the theoretical journal Psychological Review in 1913,14 although the basic idea had been floating around for a decade or more.15 In the next few years, Watson followed up with several books advocating behaviorism. He was reacting against the doctrine of introspection, the idea that the basic data of psychology could be gathered from one’s own consciousness or reports of the consciousness of others. Émigré German behaviorist Max Meyer (1873–1967) made this distinction between private and public events explicit in the title of his introductory text, Psychology of the Other One (1921).

The idea that people have access to the causes of their own behavior via introspection has been thoroughly discredited from every possible angle. Take the “tip-of-the-tongue” phenomenon. Everyone has had the experience of being unable to recall the name of something or someone that you “know you know.” The experience is quite frequent in older people—that’s why old folks’ groups often sport nametags, even if the members are well known to one another. Usually, after a while, the sought name comes to mind—the failure to recall is not permanent. But where does it come from and why? And how do you “know you know” (this is called metacognition, discussed in more detail later on). Introspection is no help in finding an answer to either question.

The great German physicist and physiologist Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894) pointed out many years ago that perception itself is a process of unconscious inference, in the sense that the brain presents to consciousness not the visual image that the eyes see, but an inferred view of the world. A given image or succession of two-dimensional images can always be interpreted in several ways, each consistent with a different view of reality. The brain picks one, automatically, based on probabilities set by personal and evolutionary history.16 I will show later on that this view of the brain as a categorizer provides a simple alternative to mentalistic accounts of consciousness.

Perhaps the most striking illustration of the inferential nature of perception is the Ames Room (Plate 1.3).17 Viewed through a peephole (i.e., from a fixed point of view), the girl in the room appears to be large or small depending on where she is in the room. The perception is wrong, of course. Her size has not changed. The reason she appears to grow as she moves from one side of the room to the other is that the brai...