- 500 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Mental Retardation, now in the third edition, was hailed as a classic when it was first published in the 1970's. This edition provides up-to-date material on the major dimensions of mental retardation-its nature, its causes, both biological and psychological, and its management.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mental Retardation by George S. Baroff,J. Gregory Olley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

| 1 CHAPTER |

The Nature of Mental Retardation

This is a book about people—children, youth, and adults who have difficulty in coping with activities of daily life because of impaired general intelligence. The extent of their difficulty is primarily related to the degree of intellectual impairment, although it also is much affected by both society's general attitude toward individuals with limited intelligence and the services provided to them. For those with mild intellectual impairment, the impact is greatest in the scholastic, vocational, and social domains. At levels of moderate, severe, and profound intellectual impairment, virtually every aspect of living is affected, the paramount consequence being to render the person incapable of assuming the degree of independence and personal responsibility expected for someone of his or her age.

The book covers each of the major dimensions of the disorder—its nature, its causes, and its treatment or management. The first two chapters examine its nature, the focus being on its intellectual, personality, and adaptive consequences and their impact on parents and siblings. In the next three chapters causation is explored, both biological and psychological. The remainder of the book is devoted to how we attempt to assist individuals with retardation1 and their families, its management or treatment. This involves a description of the range of services developed for its prevention, detection, and habilitation throughout the life span—from infancy to older adulthood. The aim of habilitative services and “supports,” is to enable the individual to achieve his or her2 level of adaptive competence and life satisfaction, a goal not different from yours and mine.

In this chapter we consider the nature of intelligence (it is the impairment in this capacity that is the essence of the disorder); issues related to who is classified as mentally retarded; the prevalence and causation of retardation; the most recent definition of the disorder, the 1992 version of the American Association on Mental Retardation (Luckasson et al., 1992); the nature of intellectual functioning in mental retardation; the quality of the thinking and adaptive functioning of those with retardation; the “developmental” nature of the disorder; its impact on the family; and adaptive potential in relation to chronological age and degree of retardation.

□ On the Nature of Intelligence

Because we all use the word “intelligence” and assume that its meaning is understood, it behooves us to consider what it really does mean to us. In a survey of the general population, three behaviors were equated with intelligence: practical problem solving, that is, reasoning logically, seeing all sides of a problem, keeping an open mind; verbal ability, that is, being a good conversationalist, enjoying good reading; and social intelligence, that is, being sensitive to social cues, admitting mistakes, and displaying interest in the world at large (Neisser, 1979). These popular conceptions also are shared by theorists on intelligence (e.g., Sternberg, Conway, Ketron, & Bernstein, 1981) and in varying ways are incorporated in tests of intelligence.

Underlying “Factors” and “Processes”

Intelligence is manifested in our ability to learn, in the knowledge that we come to possess, and in our everyday coping behavior. But what underlies this most valued human capacity? We now consider what are regarded as the basic building blocks of “intelligent” behavior. These can be conceptualized in terms of basic mental capacities and problem-solving processes.

Basic Mental Capacities: The “Factorial” Approach

A product of the statistical technique of factor analysis, the factorial approach seeks to isolate the fewest common denominators or factors that account for the correlations between measures of intelligence. Two main factorial theories can be distinguished—intelligence viewed either as a relatively unitary phenomenon or as an amalgam of relatively independent abilities.

Intelligence as Relatively Unitary. The means by which modern researchers have sought to discover the fundamental ingredients of intelligence is through the statistical technique of factor analysis. In the field of intelligence, it is used to isolate the fewest common denominators or factors that account for the correlations between measures of intelligence. Earlier views of intelligence tended to see it as a single or unitary phenomenon, one that manifested itself in virtually all aspects of cognition. Termed the general factor or g it was first identified by Spearman (1923, 1927) and characterized as the ability “to educe relations,” that is, to engage in deductive reasoning. It is this mental process, for example, that is utilized in understanding “analogies,” such as a lawyer is to a client as a doctor is to a … (Sternberg, 1981).

The prominence of g lies in the finding that various measures of cognitive functions that would be regarded as forms of “intelligence” tend to correlate with each other. This is not surprising because they share a common basis for the establishment of their “validity” as tests of intelligence: academic educability. Our capacities to read, write, and calculate, traditionally have been accepted as evidence of intelligence, and our intellectual abiltiy commonly is judged by the speed and accuracy with which we perform these functions. In effect, intelligence tests share common content because they were validated on their capacity to predict school achievement.

But the significance of g is not limited to our academic capabilities. The capacity to reason pervades our mental lives, not only the serious work-a-day world but also in the recreational realm. The games we play, for example, commonly require the use of strategies, and in their employment we exercise the ability to reason.

In addition to g, Spearman recognized the existence of what he called “specific” abilities, but he left to future researchers to clarify their nature. Prominent earlier representations of specific abilities are those of the Thurstones' (1941) “primary mental abilities,” Vernon's (1950) two-factor model, and Guilford's (1967) mental “operations.”3

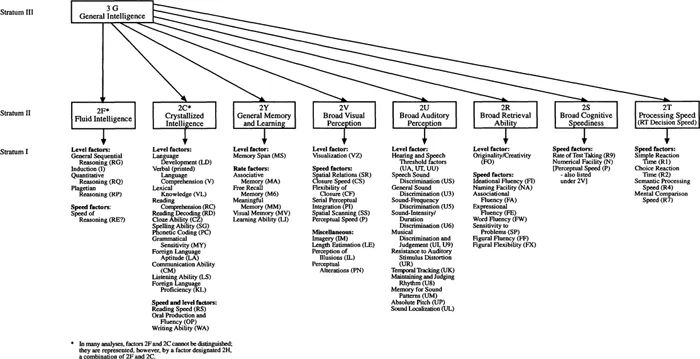

Intelligence as Multifactorial. In contrast to the earlier view of intelligence as a largely unitary capacity, multifactor theories portray it as a melange of relatively independent abilities. The role of the general factor, g, continues to be recognized, and current models of intelligence include it as the uppermost stratum in a hierarchy of cognitive abilities. The general factor sits atop the hierarchy, and beneath it is nested a group of relatively unique specific or special abilities. The hierarchy of cognitive abilites, the ingredients of intelligence, may be represented at several levels of depth. Immediately below g are found a group of “broad” specific abilities, each of which itself subsumes more distinct or derivative abilities. This hierarchy is shown in Figures 1.1 and 1.2.

The model of intelligence shown in Figure 1.1 (Carroll, 1993) represents our current understanding of the nature of intelligence as this is revealed through factor analysis. With our cognitive abilities organized in terms of

FIGURE 1.1 A three-strata hierarchical representation of cognitive abilities. (Reprinted permission from J. B. Carroll, Human cognitive abilities, Cambridge University Press, 1993.)

three strata, g as “general intelligence” appears at the apex of the hierarchy in stratum III. At stratum II are found eight broad abilities, each receiving some contribution from g but also representing its own distinctive cognitive dimension.

Reading from left to right, the first two broad abilities are fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence. The special contribution of Cattell (1971) and Horn (1968) fluid intelligence is equated with logical reasoning and crystallized intelligence with knowledge acquired through language. In its focus on logical reasoning, fluid intelligence largely would resemble g. Of these two forms of intelligence, the crystallized version is seen as very dependent on education; the fluid form may be more “native” or biological in its basis.

The other six broad abilities are general learning and memory, referring to immediate or short-term memory; broad visual perception, a mental ability central to spatial and mechanical understanding; broad auditory perception, sensitivity to various aspects of sound, such as speech sounds and rhyme; broad retrieval ability, the facile production of ideas, an ability pertaining to “creativity”; and two abilities related to “mental” speed—broad cognitive speediness, the speed of responding, and processing speed, reaction time and information-processing speed.

At stratum I, beneath each of the broad abilities are a large number of “narrow” or more specialized variants of the broad ability. At least 60 are now known (Carroll, 1997). Under fluid intelligence, for example, are found four kinds of reasoning—sequential, inductive, quantitative, and Piagetian. Of these, g was particularly associated with inductive reasoning. Crystallized intelligence encompasses a much wider number of narrow language-related abilities, such as language development, the understanding of language, knowledge of language structure, and reading decoding.

Specific Abilities and Intelligence Tests. The measurement of specific abilities has typified tests of intelligence. The most recent version of the venerable Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale, its fourth edition (Thorndike, Hagen, & Sattler, 1986), is organized around the assessment of crystallized and fluid intelligence and memory. Figure 1.2 shows the cognitive hierarchy with g at stratum III, the three broad abilities at stratum II, and components of crystallized and fluid intelligence at stratum I. In fact, the characterization of the subtests within the scale conform to stratum I—verbal reasoning and quantitative reasoning under crystallized abilities and abstract-visual reasoning under fluid-analytic abilities. Note that “reasoning” is evaluated in both crystallized and fluid forms, the distinction pertaining to language in the former and the use of visual tasks in the latter.

A very similar array of “specific” abilities is found in the Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery (Woodcock & Johnson, 1989), an intelligence test widely used in school settings. The Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (K-BIT) (Kaufman & Kaufman, 1990) is organized around two broad abilities—crystallized and fluid intelligence.

Before terminating this section, it should be noted that recent researchers have expanded the array of specific abilities to include such capacities as “practical” and “social” intelligence. The former is equated with competence in the everyday world (e.g., Sternberg and Wagner, 1986), and the latter with effectiveness in social or interpersonal situations. Although both are relevant to the problems confronting people with mental retardation, impairment in social intelligence is of special interest. Lack of sophistication and social awkwardness are prominent features of mental retardation. There is a diminished awareness and sensitivity to what is appropriate in social situations. This is also characteristic of persons with the developmental disorder of autism, in whom retardation is commonly present, and is found even in those whose intellectual functions are normal. In retardation, how...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 The Nature of Mental Retardation

- 2 Personality and Mental Retardation

- 3 Biological Factors in Mental Retardation: Chromosomal and Genetic

- 4 Nongenetic Biological Factors: Prenatal, Perinatal, and Postnatal

- 5 Psychological Factors in Mental Retardation

- 6 Introduction to Services and Supports

- 7 Services and Supports to Children and Youth

- 8 Services and Supports to Adults

- 9 Maladaptive or “Challenging” Behavior: Its Nature and Treatment

- 10 Psychiatric Disorders in Mental Retardation

- References

- Index