- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bertolt Brecht

About this book

Bertolt Brecht's methods of collective experimentation, and his unique framing of the theatrical event as a forum for change, placed him among the most important contributors to the theory and practice of theatre. His work continues to have a significant impact on performance practitioners, critics and teachers alike. Now revised and reissued, this book combines:

- an overview of the key periods in Brecht's life and work

- a clear explanation of his key theories, including the renowned ideas of Gestus and Verfremdung

- an account of his groundbreaking 1954 production of The Caucasian Chalk Circle

- an in-depth analysis of his practical exercises and rehearsal methods.

As a first step towards critical understanding, and as an initial exploration before going on to further, primary research, Routledge Performance Practitioners are an invaluable resource for students and scholars.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

A Life of Flux

Which Brecht?

Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956) would have been wary of any introduction that presented him as a fixed monolith, rather than acknowledging that there were ‘almost as many Brechts as there were people who knew him’ (Lyon 1980: 205). For he was an ever-changing lover of flux who came to believe that we are contradictory beings, constantly modified by our interactions with the social and material world, and by the eye of each new beholder. And there have been many beholders, each with their own stance on this contentious subject. Some describe him as Europe’s most famous Marxist playwright, director and theatre theorist. Or, Germany’s answer to Shakespeare, but with a political twist. Others regard him as a genius who, despite his unfortunate political credo, remained a poet of eternally suffering and enduring humanity. Given that Brecht developed a respect for Marx, Shakespeare and fame he might not have objected to two of these descriptions. But it is this writer’s position that Brecht had little time for the idea of eternal suffering.

One of the aims of this chapter is to capture the changeful nature of Brecht’s political attitudes and artistic practice and to locate some of its sources. These include his acute responsiveness to Europe’s tumultuous political landscape between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the Cold War. In order not just to survive this upheaval, but also to prosper from it, Brecht had to be constantly on the move. Ironically, the sources of instability in his life played a role in fostering its continuities, especially his passion for experimental learning, collaboration and fighting oppression. Faced with immense social upheaval, Brecht’s consistent response was to celebrate and attempt to master change. This book places particular emphasis on that attempt because it seeks to explain why Brecht is still a beacon for political performance makers. It could have told a less flattering or even opposing tale. But in an age like ours, where capitalism threatens to suppress alternative social models, celebrating the insightful practice of a contestatory voice and his collaborators seems a timely and necessary strategy.

On the Make: From Bavaria to Berlin (1898–1924)

Born by the Lech

‘Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht’ was born in the Bavarian city of Augsburg on 10 February 1898 at 7, Auf dem Rain, in a building flanked by canals of the river Lech. The apartment was noisy, due to the rushing waters and the file cutter’s workshop on the ground floor. However tiresome the noise may have been for its inhabitants, its causes – the water and the labourer – provide rich metaphors for a biographer foregrounding Brecht’s long-held interest in flux and the cause of the worker. The choice of lodgings probably stemmed from the realities of his father’s modest income – Berthold Friedrich was a commercial clerk for the Haindl paper factory. After the birth of Brecht’s brother, Walter, the family took up residence in the so-called ‘Colony’, a group of four-storey houses built by the Haindl founders for the benefit of needy employees. Brecht’s father, promoted to company secretary, was in charge of the administration of this social housing, his family privileged with an entire floor to themselves as well as two attic rooms. Unlike the majority of their neighbours, they could afford live-in servants.

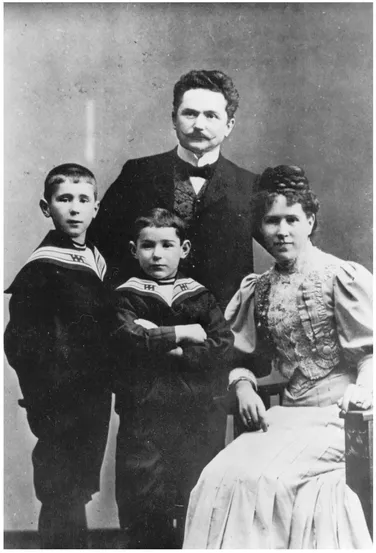

The lifestyle of the Brecht family (Figure 1.1) was typical of the bourgeoisie during the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II (1888–1918), king of Prussia and last emperor of all the states in the German

Figure 1.1 Brecht aged 10 with his father Berthold Friedrich, his mother Sophie and his brother Walter. © Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, image courtesy of BBA

commonwealth. The work ethic and aspirational energy modelled by Brecht senior, who in 1917 became the managing director for Haindl, informed the career attitude of his sons. By his mid teens Brecht junior was already in hot pursuit of fame as a literary figure and his brother would become a professor in the field of paper technology. The patriarchal and class dynamics of the Wilhelminian empire were manifested in the family’s strict sexual division of labour – with women relegated to domestic work – and in its observance of class segregation – although the boys played and fought with their working-class neighbours, Brecht’s grammar school was an exclusively middle class (and macho) experience. During the exile years in Denmark, he would look back scathingly at his ruling class upbringing:

I grew up as the son

Of well-to-do people. My parents put

A collar round my neck and brought me up

In the habit of being waited on

And schooled me in the art of giving orders.

Of well-to-do people. My parents put

A collar round my neck and brought me up

In the habit of being waited on

And schooled me in the art of giving orders.

(Brecht 1979c: 316)

When Brecht wrote this poem he had already proved himself a commanding leader, in the best and worst sense. And one whose behaviour throughout his life was characterized by both a condemnation and a continuation of stifling bourgeois habits.

Historicizing Interlude

Now, let’s stop this biographical flow for a moment. From the ‘Born by the Lech’ episode, what have you learned about the author’s attitude towards her subject matter? Why do you think she selected that material and organized it in that way? How does her telling of the tale reveal her historical context, her worldview, her politics? And why has she sometimes used the rather strange strategy of referring to herself in the third person and past tense? These are the types of questions Brecht asked when reading any type of expression, history texts in particular. And he would have started asking these questions from the word ‘go’, interrupting the flow of the narrative with analytical commentary.

Had Brecht read the opening section of this biography he would have quickly grasped the point of the third person references to ‘the author’, for he used the same distancing strategy in many of his own reflective writings. Through this choice of narrative voice he communicated his interest in analytical observation of one’s own position, and in treating the self as historical rather than eternally present. He would also have recognized that, rather than telling a tale of inborn genius, the biographer was seeking to demonstrate how his ever-changing material, social and historical circumstances conditioned his thought – an approach in keeping with his own. Brecht would have noted too how she emphasized the material circumstances and associated thoughts and habits of his family, focusing on their relationship to work, to a bourgeois ethos of self-improvement and social mobility and to class and gender division. And he would have understood the Marxist social class terminology:

- bourgeoisie: When Brecht's father became managing director, he joined the ranks of the bourgeoisie, the capitalist owners of merchant, industrial and money capital who in nineteenth-century Europe replaced the land-owning aristocracy as the economic class in control of the bulk of the means of production.

- petite bourgeoisie: Prior to Brecht senior's promotion, he belonged to the group of people, like office workers and professionals, who do not own the means of production but may buy the labour power of others (such as domestic servants) or own small businesses, like the file cutter. Brecht would often apply the term to people who had some economic independence but not much social influence, such as white-collar workers and small shopkeepers.

- proletariat: At the Haindl paper mill, Brecht's father employed and made company profit from wageworkers, members of the proletariat or industrial working class, whose means of livelihood was to sell their labour to property owners (for further clarification of Marxist class terminology, see Glossary).

As you read on, see if you can spot other features of the biographer’s position, including the influence of socialist and feminist thought.

War Poet: Patriot and Rebel

Even prior to the outbreak of the First World War (1914), Brecht and his grammar school classmates at Augsburg’s Royal Realgymnasium were indoctrinated in a monarchist and militant nationalism. When Germany officially declared war, Brecht was exempted from active duty owing to his heart condition – he suffered heart cramps and palpitations from an early age. Instead, he chose to serve the fatherland through a series of patriotic texts for the local papers. Under the pseudonym ‘Berthold Eugen’, he praised the Kaiser’s leadership, calling for donations to support families who had lost their breadwinner, and eulogizing self-sacrificing German mothers who put their grief for lost sons behind them and devoted themselves to prayers for victory.

Brecht’s pathos-laden jingoism was gradually replaced with a sceptical, realist attitude. In keeping with his new, hard-hitting approach, in 1916 he began to use the terse signature ‘Bert Brecht’. In June of that year, the critical tone of a school essay brought him close to being expelled. When asked to write about Horace’s revered pronouncement Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori (‘It is sweet and honourable to die for the fatherland’), Brecht replied in combative mode that it was always hard to die, particularly for those in the bloom of their life, and that only the vacuous – and even then, only if they believed themselves far from deaths door – could present self-sacrifice as easy. This was a daring statement in a context where many of Brecht’s classmates were being sent to military training or into the heart of the fighting, some never to return and others to be maimed for life. In contrast to his brother and peers, Brecht had no desire to be a hero, managing to avoid military service almost until the end of the war.

After completing school in May 1917, Brecht carried out auxiliary war-worker duties as a cleric and gardener, and was later employed as a private tutor. In October he matriculated at the Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich, taking courses in literature for two semesters, before suddenly transferring to medical studies. There is little evidence that Brecht applied himself to medicine, and in the summer semester of 1921 he failed to sign up for any lectures. It seems likely that Brecht’s transferral arose from a need to ensure that if he were conscripted, it would be as a medical orderly rather than as a soldier. As Brecht said to his life-long friend and future scenographer, Caspar Neher, he would rather collect feet than lose them.

From October 1918 to January 1919 Brecht worked on a venereal disease ward of a military hospital, which, in keeping with the topsy-turvydom of the times, was erected in the playground of an Augsburg primary school. It was during this period that he wrote the famous, politically explosive poem ‘Legend of the Dead Soldier’, a scathing parody of the heroic grenadier figure in German literary ballads who rises from his grave and nobly steps back into battle. Brecht turned the literary tradition on its head by presenting the soldier as a stinking corpse, who, on the whim of the Kaiser, is ‘resurrected’ and declared fit for service by an army medical commission. After pouring schnapps down the soldier’s throat, painting over his filthy shroud with the black-white-red of the old imperial flag, and hanging two nurses and a half-naked prostitute in his arms, they parade him through the villages. The next day, as he has been taught, he dies a hero’s death. The shocking nature of Brecht’s attack on idealized heroism was intensified by the contrast between the grotesque imagery of the lyrics and the gentle and sentimental melody, an oppositional technique that would become a trademark of his epic and dialectical theatre. The satirical force of the ballad, often performed by Brecht to guitar accompaniment, was such that in 1923 it earned him fifth place on the Nazi’s list of people to be arrested once they were in power.

Brecht’s rebellion against authoritarianism indicates an early interest in power structures, a rebellion motivated at this stage more by a concern with his own empowerment than any revolutionary vision of large-scale social change. The desire to be top dog himself would characterize aspects of Brecht’s life-long behaviour, in some cases leading to a perpetuation of invidious power relations. For example, his frequently commandeering and proprietorial treatment of women recalled the habits and double standards of his imperial forebears. At the same time that Brecht was convincing Paula Banholzer – the mother in 1919 of his first child, Frank – to break off her engagement with another man and remain loyal to him, he was pursuing the opera singer Marianne Zoff, soon to become his first wife and mother of his daughter Hanne. Brecht’s desire to orchestrate and sustain multiple love relationships at any one time bears some relation to ‘his delighted, sometimes obsessive engagement with collective activity’ as well as his ‘tendency to take the lead in such activity’ (Thomson, in Thomson and Sacks, 1994: 23).

Brecht’s simultaneous encouragement of ‘think-tank’ collectives embodied a relatively egalitarian version of this engagement. In Augsburg these groups consisted of a circle of predominantly male friends who often met in Brecht’s attic room, where there would be singing and music making, discussion, reading and reciting. From the mid-1920s onwards, working-class and female members – especially lovers – were increasingly represented as co-workers. Brecht spearheaded and led these collectives – a significant number of his plays, including world-renowned texts like The Threepenny Opera, Mother Courage and Her Children and The Caucasian Chalk Circle, were written and researched in collaboration with others. And it was he who basked most in the fame and royalties they brought. Nevertheless, for the majority of participants who chose to be involved, they were exciting and relatively democratic forums where creative productivity was fostered en masse.

A Swine and His Creature Comforts

The post-war period would not have been an easy time to become a breadwinner, especially if your aim was to forge a career as a poet. Brecht’s response to a social context riven by hunger, unemployment and hyperinflation was to assert – both in his private life and through his art – the nature and importance of material needs and survival strategies. His increasingly materialist outlook – the philosophical view that everything that really exists is material in nature and that everything mental is a product of phenomena that can be accessed through the senses – was at odds with expressionism, the dominant experimental theatre in the early post-war years. The expressionist movement contained diverse and often contradictory tendencies, but many of the playwrights were idealist in so far as they thought non-material mind and spirit were the prime shaping forces of human experience and the world. Their idealism partly explains the so-called ‘New Man’ figure found in many of their plays, including Friedrich from Ernst Toller’s The Transformation (1919), a poet-leader who seeks to change the world through visionary speeches that rejuvenate community spirit.

Brecht’s play Baal is an expression of his irritation with expressionist idealism and pathos. The first version of the play – it became customary for Brecht to revise or adapt earlier work in the light of new circumstances – was written in the spring of 1918, within a month of the Munich Chamber Theatre production of Hanns Johst’s The Lonely One. Energized by his love of opposition, Brecht proclaimed that he could write a better play than Johst’s expressionist drama, but the resulting counter play was by no means totally oppositional. For example, both texts are episodic presentations of men experiencing social alienation. And as in other expressionist work, Baal depicts a journeying, semi-autobiographical protagonist. Brecht’s contestatory attitude, as well as his tendency to preserve aspects of the contested model, remained a hallmark feature of his creative approach. Johst presents his protagonist as a lonely playwright genius, misunderstood by the inferior mass. Baal is also a writer, but he is an earthly hedonist who puts drink, food and sex before his poetry. Rather than being a superior and isolated soul, Baal is an insatiable, desiring body who interacts voraciously, guided purely by his own pleasure and greed for sensual experience with men, women and nature. Unlike Toller’s poet-leader, his journeying does not lead to heroic self-transformation. Rather, seemingly worn down by rough living and an asocial existence, Baal simply merges with matter: on a stomach full of stolen eggs, he dies alone in the dirt of a forest.

Brecht’s vagabond outsider, Baal, embodies a deep dissatisfaction with imperial Germany. Like his favourite playwright at the time, Frank Wedekind, Brecht’s shockingly transgressive expressions constituted a rebellion against duty, conformity and suppression of desire. But the revolt was circumscribed by a focus on his own freedom and notoriety, and an unwillingness to commit to any political agenda for change. While Brecht was immersed in Baal, and the pleasures of the local fairground, others were choosing the path of martyrdom in defence of the newly proclaimed Bavarian Republic. During the political chaos after the Kaiser’s abdication, left-wing activists – including Ernst Toller – seized the opportunity to oust the king of Bavaria and assert a socialist government. It was declared on 9 November 1918 in Munich by Kurt Eisner, who was the poet-leader of Germany’s Independent Social Democrat Party (USPD). In an attempt to ensure grass-roots involvement in government, the Republicans instituted workers’...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- 1 A LIFE OF FLUX

- 2 BRECHT'S KEY THEORIES

- 3 THE CAUCASIAN CHALK CIRCLE·. A MODEL PRODUCTION

- 4 PRACTICAL EXERCISES AND WORKSHOP

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Bertolt Brecht by Meg Mumford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Drama. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.