![]()

1 Working the Land in Preindustrial Europe and America

Americans often hold conflicting images of technology and its role in the history of the United States. In particular, many people look nostalgically upon the world before factories and mega-cities as a time of harmony with nature, close-knit communities, and hard but satisfying work. This romantic impulse to critique the modern world by finding a lost paradise in the past has been a common response since the beginnings of industrialization. Others adopt an opposite response that is equally as old. These ‘modernists’ see the traditional world as insecure and, for the vast majority, impoverished, requiring unrelenting labor to survive, and making people paranoid and superstitious.

These differences reveal contrasting feelings that many of us hold about the modern world. The romantic view of traditional society has often pointed to the human costs of modern technology: the loss of the beauty of nature, the decline of personal contact with familiar faces, the disappearance of the joy that came from making things from scratch, and the loss of a seemingly natural pace of life. Craft historian Eric Sloane (1955) offers such a romantic image of the colonial landscape: “Close at hand there were lanes with vaulting canopies of trees and among them were houses with personalities like human beings. At a distance, it was all like a patchwork quilt of farm plots sewn together with a rough black stitching of stone fences. But the advance of ‘improvements’ has done blatant and rude things to much of this inherited landscape.”1

By contrast, the modernist sees technological progress as the harbinger of greater personal comfort and security, the herald of both individual freedom and greater economic and social equality, and the vehicle of human creativity and sheer wonder. Most of us probably agree with a bit of both perspectives—although we may lean one way or another. The task of the historian, however, is to try to go beyond these romantic and modernist ideologies and to present a subtler—and, hopefully, more accurate—picture of how technology has shaped American society today. And to do this we must begin with how Americans worked and coped with their environments before modern machinery and technology.

In order to understand this old world of American technology, we must recognize its origins in the Old World of Europe. Not only did European settlers in North America bring with them technologies and patterns of work that they had known in the Old World, but long after they had arrived, immigrants and their children continued to rely on European methods of farming and manufacturing. With notable exceptions, settlers depended upon European technological innovations during early industrialization. In the 1790s, Samuel Slater of Rhode Island copied British textile machinery rather than inventing something new. At that time, Europeans and many Americans considered the New World to be a technological backwater, from which Europeans could expect only to obtain raw materials like cotton and wood for their industrial needs. North America was bound to be a land of inferior manufactures fit, at best, for local consumption. Only after 1800 did Americans begin to change this dependence upon Europe. Even then, innovation was often a transatlantic phenomenon. The history of technology in the United States cannot be isolated from that of Europe.

Yet, Americans deviated from European antecedents. From colonial times, settlers encountered vastly different physical conditions from those of Europe: distinct and unfamiliar topography, water, mineral and soil resources, and climatic conditions, for example. Colonists learned from native peoples how to adapt to this strange new environment. And settlers represented a self-selected migration of Europeans with particular expectations and skills. These factors led to unique paths toward economic growth and innovation in the New World. Yet, the colonial economy was also hampered by a scarce and scattered population that greatly encumbered the task of finding suitable workers or reaching markets. These unique opportunities and challenges meant that Americans followed particular avenues toward modern industrialism. Nonetheless, Americans are often too prone to overemphasize their heritage of exceptional ‘Yankee Ingenuity.’ If we recognize the legacy and linkages with Europe, we can better understand why, when, and to what extent Americans differed from (and sometimes led) the wider world in technological innovation.

Crops, Animals, and Tools: European Antecedents

We must begin our survey of technological change in American history with a brief overview of its origins in European agriculture. At its heart was the cultivation of grain—especially rye, oats, barley, and, of course, wheat. Rice was grown in parts of Italy (and by the end of the seventeenth century in the Carolinas), but rice was considered only an emergency food to feed the starving poor. The range of vegetables in Europe was narrow: The English grew various dry peas and beans, turnips, and parsnips, which supplemented grains, provided cheap protein, and could keep long periods. Farmers, however, did not specialize, growing most of what they consumed themselves. And they had to cope with insect and fungal outbreaks that often led to sickness. Europeans in general were peoples of grain. Around the cultivation of these cereal crops were built technologies of planting, plowing, harvesting, storing, milling into flour, and even transportation, requiring a wide variety of cereals and vegetables to be planted.

Europeans were also meat eaters. In the 1200s, while China was building a civilization based on biannual harvests of lowland aquatic rice, medieval European aristocrats were feasting on beef, pork, and fowl. Even the poor occasionally enjoyed the protein of meat and more frequently of cheese. Europeans were thus likely healthier and stronger than others with a more monotonous diet. But this ‘privilege’ was paid for at a high price: Meat production was an inefficient source of calories, placing severe limits on European population growth. China’s intensive use of land in rice cultivation made possible a large population, whereas Europe’s ‘waste’ of scarce land for animal pasture and grain for fodder reduced the potential size of families.

Wheat was inefficient when compared with the rice technology of Asia or the corn (or maize) agriculture of Mesoamerica. Between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries, for every three to seven grains of wheat harvested, one grain had to be set aside for the next year’s seed. By contrast, each maize seed (or corn) produced 70 to 150 grains in seventeenth-century Mexico. By comparison today American wheat fields yield 40–60 times the seed sown. Old World wheat also depleted soils rapidly unless land was regularly allowed to recover, by periodically leaving fields unplanted. This fallow land was often tilled to aerate the soil, fertilized with manure, and allowed to regain vital salts. Animals and grain competed for land and this probably encouraged Europeans from the fifteenth century to seek virgin soils in the temperate climates of the Western and Southern Hemispheres, including what became the United States.

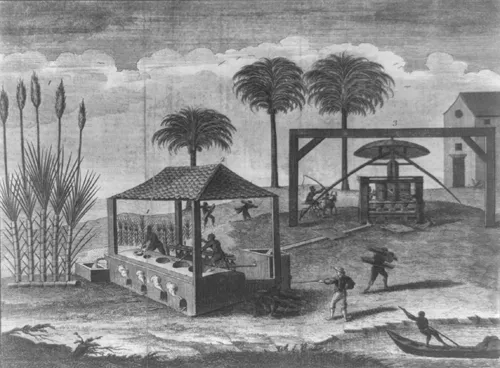

Of vital importance was the ‘Columbian Exchange’ of plants and animals that began with European landings in the New World. European explorers were quick to see the advantages of ‘Indian corn,’ with origins in the American Southwest and widely cultivated by indigenous people. Sugar, a rarity in the diet of medieval Europeans, became a very profitable import from the West Indies and Brazil by the end of the seventeenth century, resulting in the mass enslavement of Africans for labor on sugar plantations. Of equal importance was tobacco from the Caribbean that was first introduced to Europe by the Spanish soon after Columbus’s arrival. It became the cash crop of Jamestown Virginia colonists in the early seventeenth century. Until the eighteenth century, European farmers resisted another New World food, the tomato, some fearing that it was poisonous. Only with considerable ingenuity (much by American farmers and cooks) did it become a staple in salads and pasta on both sides of the Atlantic. The potato, another New World food, originated in the Andes of South America. Though it was brought to Europe around 1660, peasants resisted its cultivation until the 1790s when it fed a growing population of poor farmers. This modified stem that grows underground was originally toxic, but the Andean Indians gradually bred safe varieties. Potatoes were critical to European peasants: They could be harvested in three months before grain matured. Dependency on the potato crop would lead to the Irish Famine in the 1840s, when disease struck that vegetable. Also, important exports from the Americas were sweet potatoes (very important to China), pumpkin, and many types of beans (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 An English lithograph by John Hinton (1749) of a West Indies sugar plantation and slaves crushing and boiling the cane.

Credit: Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

The Columbian Exchange of foods between Europe and the Western Hemisphere also went from east to west: Europeans brought pigs, sheep, cattle, and horses to the New World as well as wheat and rice. Pigs reproduced and matured quickly, and cattle could feed on grass (inedible to humans), providing not only dairy and meat, but leather and much else to the early colonists. Horses, first brought by the Spanish in the sixteenth century, were critical for the European colonists, but they also transformed the lives of the native peoples of the Plains.

Despite the inefficiency of European agriculture and the slow adoption of New World crops in the Old, European agriculture had many advantages that would give Western culture an edge over the East (and the indigenous peoples of the Americas). Animal husbandry was essential to Western civilization; it provided not only protein, hides, and fiber for clothing, and fertilizer for farming, but labor-saving work. Wheat farming generally required draught animals, especially the horse and the ox, to plow and harrow land. Although water buffalo and horses were available in China and India, they were relatively rare in the rice paddy. An eighteenth-century observer claimed that seven men were required to pull as much weight as could a horse. And the horse gave Europeans (and others) mobility for trade and conquest. By the seventeenth century, animal breeding had produced highly specialized horses for work, racing, and other purposes. Perhaps by 1800, there were 14 million horses and 24 million oxen in Europe. Animal power saved much human labor even though land had to be devoted to feeding.

Another Western advantage was the prevalence of wood and its products. Northern European civilization emerged out of the forests. These people depended on wood for heating and cooking fuel, housing construction, most machinery (including waterwheels and even clocks), ships and wagons, and even the fuel necessary for the smelting and forging of metals. Wood was an ideal raw material for a low-energy civilization: it was easily cut, shaped, and joined for the making of tools; it was stronger, lighter, and more malleable than stone for many purposes; and it could be cheaply transported by floating on water.

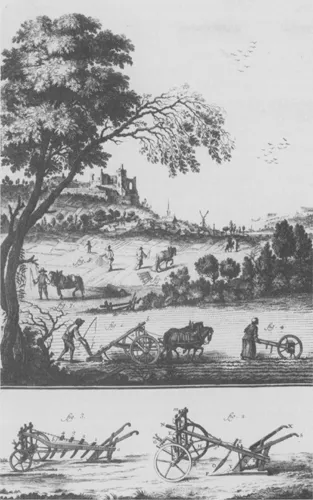

However, wood was flammable and inefficient as a fuel. It lacked durability and tensile strength, especially as moving parts in machines, or as cutting or impact tools like plows or mallets. An even greater problem was deforestation, making coal a viable alternative to wood as a heating and smelting fuel. Especially after 1590 in England, ordinary wooden buildings were replaced with brick and stone. Still later, iron would be substituted for wood in machine parts and other uses, but this took a long time. Shortage of specialty wood in the seventeenth century, especially for boat masts, caused Europeans to seek new sources in New World forests (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Mid-eighteenth-century plowing (figs. 1–3), seeding (figs. 4, 5), harrowing (fig. 6), and rolling (fig. 7).

Credit: Diderot’s Encyclopedie, 1771.

European civilization and its American outposts were built around grain, animals, and wood through the eighteenth century. Essential to agriculture were simple wooden tools: The plow, harrow, sickle, flail, and millstone were all known in ancient Egypt and Rome. Oxen or horses pulled the plow, a fairly complex tool that dug into the soil to cut and turn over furrows, thus aerating the soil for seeding. Fields were first sliced vertically by the plow’s sticklike coulter, which was followed by the share, which made a horizontal cut beneath the furrow slice. Behind the share was a broad moldboard that was set at an angle to turn over the furrow and to bury the old stubble. Nevertheless, peasants on small farms continued to use hoes, spades, or hand-held breast plows until the end of the eighteenth century.

Next, the farmer used a harrow. This tool often consisted of a triangular or rectangular frame studded with pointed wooden sticks. Harrows were dragged across previously plowed land to clean out weeds, pulverize cloddy soil, and smooth the surface for planting. Seeding was often done by simple broadcasting. Increasingly, however, from the seventeenth century, farmers adapted the less wasteful (if more time-consuming) method of dibbling. This was a process of depositing seed in a hole ‘drilled’ by a handheld pole with a pointed end. This allowed for more uniform row planting and eased the time-consuming task of weeding.

Harvesting grain likely created the greatest problems for farmers. Nothing was more critical than cutting or reaping the plant and threshing or separating the grain from the plant head. Reaping was a very time-consuming activity. Especially with wheat, there were only a few weeks to get this job done before the grain shriveled or dropped to the ground to be wasted. The threat of rain or wind always made this job more urgent. Until the eighteenth century, the curved blade of the sickle remained the almost universal tool for cutting stalks of grain. Equipped with a sickle, a worker could reap about a third of an acre per day.

Helpers gathered the stalks on the ground into shocks for easier shipment to the barn for later threshing. Threshing was often done with a flail—a simple tool composed of a long handle (or staff) to which a shorter club (the swiple) was loosely attached with a leather cord. The thresher simply laid harvested grain stalks in a line across a barn floor. The farmer then beat the heads with the swiple until the grain had separated and the straw could be swept away. The remaining grain had to be winnowed, blowing away the straw or chaff still attached to the grain. This was often done si...