![]()

Part I

![]()

1

Understanding Water Institutions:

Structure, Environment and

Change Process

R. Maria Saleth

Introduction

As the limits of the physical and technical approaches to water resource management are becoming more and more transparent, policy attention is shifting increasingly towards institutional reforms. In fact, the institutional arrangements governing the water sector have experienced remarkable changes in many countries around the world, especially during the past decade or so. These changes, which are more due to purposive reform programmes than to any natural process of institutional evolution, can be observed both at the macro and national levels (eg enactment of water laws, declaration of water policies and organizational reforms) and at the micro and sub-sectoral levels (eg irrigation management transfer, informal water markets and privatization of urban supply). These changes and their implications for water resources management are well documented with varying coverage, details and perspectives (eg Easter et al, 1998; Savedoff and Spiller, 1999; Dinar, 2000; Saleth and Dinar, 2000; Gopalakrishnan et al, 2005).

Despite the critical importance of institutional reforms for enhancing the development impact of water resources management at different levels, considerable divergence persists as to the way water institutions are approached and evaluated. This obviously leads to a serious dissipation of research attention and distortion in reform policies. In the process, the critical linkages between formal and informal institutions as well as the structural and spatial linkages among local, regional and national institutions are often ignored and such institutions are treated as if they were operating independently in separate spheres and being governed by different sets of factors. The reform programmes developed from such a limited and segmented understanding of water institutions often fail to have the expected impact on water resources allocation, use and management because of their inability to exploit the tactical and strategic aspects inherent in water institutions and the course of their change process. Based on the recent work of Saleth and Dinar (2004), this chapter tries to show how a better understanding of water institutions and the course of their change process can lead to reform strategies that can advance water institutional change at different levels and contexts with minimum economic and political transaction costs.

As to its specific objectives, this chapter (a) describes the nature and features of water institutions together with their practical and methodological implications; (b) conceptualizes the internal structure and external environment of water institutions; (c) reviews the relevance of existing theories and presents alternative approaches to explaining and describing the process of water institutional changes; (d) indicates how reform design and implementation principles can promote institutional reforms by exploiting endogenous institutional features and exogenous political economy contexts; and (e) concludes with key implications for the theory and practice of water institutional reforms. As regards organization, from here on this chapter is organized, more or less, in line with the objectives listed above. Although essentially theoretical and analytical in scope, it has major implications for practical policy, especially in promoting institutional reforms needed to underpin various strategies for water resources management adopted at different levels and scales.

Water Institutions: Nature and Features

Following the general definition of institutions (Commons, 1934; North, 1990a; Ostrom, 1990), water institutions can be defined as rules that define action situations, delineate action sets, provide incentives and determine outcomes both in individual and collective decision setting in the context of water development, allocation, use and management. For analytical convenience, these rules can be broadly categorized as legal rules, policy rules and organizational rules (Saleth and Dinar, 2004).1 Water institutions also share the same features as characterize all other institutions. First, institutions are subjective in origin and operation but objective in manifestation and impact (Hodgson, 1998).2 Second, they are path-dependent in the sense that their present status and future direction are dependent on their earlier course and past history (North, 1990a). Third, the stability and durability properties of institutions do not preclude their malleability and diversity (Adelman et al, 1992; Hodgson, 1998). Fourth, since institutions comprise a number of functionally linked components, they are hierarchic and nested both structurally (North, 1990a; Ostrom, 1990) and spatially (Boyer and Hollingsworth, 1997). Finally, institutions are embedded and complementary not only with each other but also with their environment as defined by the cultural, social, economic and political milieu (North, 1990a).

Implications for Institutional Change

The subjective nature of institutions underlines the central role that perceptional convergence among stakeholders plays in prompting institutional change. Indeed, the perceptional convergence that can occur through the interaction of subjective and objective factors represents the origin of the demand for institutional change. Path dependency, taken together with the relative durability and stability properties of institutions, makes institutional change essentially gradual, continuous and incremental (North, 1990a). The hierarchic, nested and complementary features of institutions suggest that structural and functional linkages among institutional components are quite pervasive. In view of these institutional linkages, a change in one institutional component can facilitate both sequential and concurrent changes in other institutional components. This suggests the scope for scale economies and increasing returns in institutional change (North, 1990a). Since institutions are embedded within the general environment characterized by a configuration of social, cultural, economic and political factors, a change in one or more of these factors can also trigger institutional change. Thus, institutional change can occur due to changes both in endogenous factors (structural features within institutions) and in exogenous factors (spillover effects from the institutional environment).

Implications for Institutional Evaluation

The implications of institutional features for institutional change are well known, but, their analytical and methodological implications are either less familiar or not yet recognized. Let us focus here on two of these implications. First, the technical features of institutions are nothing but different forms of institutional linkages. For instance path dependency relates to institutional linkages in a temporal context. Similarly, the hierarchic, nested and embedded features of institutions actually characterize institutional linkages in a structural and functional sense. Although the transaction cost implications of these institutional linkages are well recognized in the literature, the role of these linkages has not been formally incorporated as part of transaction cost theory. Second, the close resemblance between the institutional system and the ecosystem allows the development of the institutional ecology principle (Saleth and Dinar, 2004). While this principle seems trivial, it is powerful enough to provide the conceptual basis for developing the institutional decomposition and analysis (IDA) framework.

The IDA framework is a flexible tool for analytically decomposing water institutions at various levels and contexts. For simplicity, institutional decomposition can proceed in three stages. First, following North (1990a), water institutions can be decomposed into water institutional structure (governance structure) and water institutional environment (governance framework). Second, the institutional structure can be decomposed into its legal, policy and organizational components. Finally, each of these three institutional components can be decomposed to highlight their underlying institutional aspects.3 As the IDA framework enables the evaluation of the structural and functional linkages within and between water institutional structure and its environment, it provides valuable insights into the internal mechanics and external dynamics of water institutions. While we will later show the tactical and strategic implications of these insights for designing and implementing practical reform policies, let us turn now to describe the internal structure and the external environment of water institutions.

Water Institutions: Structure and Environment

To show how endogenous features and exogenous influences affect the performance impact and change process of water institutions, it is necessary to conceptualize their internal structure and external context. Water institutional structure includes the structurally nested and embedded legal, policy and organizational rules governing various facets of water resource management. Water institutional environment, on the other hand, characterizes the overall social, economic, political and resource context within which the water institutional structure evolves and interacts with the water sector. Under certain simplifying conditions, it is possible to provide a visual representation of both the structure and the environment of water institutions.

Water Institutional Structure

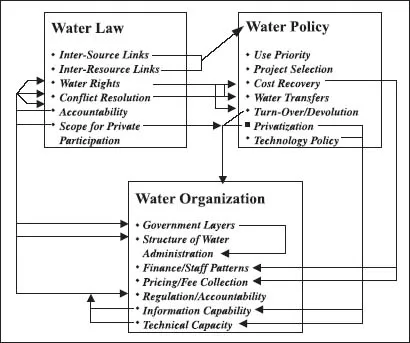

While it is possible to provide a complete description of the water institutional structure for any given national and regional context, for expositional convenience, it can be characterized in terms of some of the key legal, policy and organizational components that receive major attention in national and global debates (Saleth and Dinar, 2004). Figure 1.1 depicts such a simplified representation of water institutional structure. While Figure 1.1 is largely self-explanatory, a few points require attention. The overall performance of water institutions and their ultimate impact on water sector performance depends not only on the capabilities of their individual institutional components and aspects but also on the strength of structural and functional linkages among them.

Source: Saleth and Dinar (2004)

Figure 1.1 Water institutional structure: a simplified representation

The arrows in Figure 1.1 indicate an illustrative set of linkages possible both within and across the three institutional components. For instance, the legal aspects of how water sources and their relationship with land and environmental resources are treated within water law have linkages with policy aspects such as priority setting for water uses and project-selection criteria. Thus a water law that does not differentiate water by its source but recognizes the ecological linkages between water and other resources is more likely to encourage a water policy that assigns a higher priority to environmental imperatives and hydrological interconnectivity in project selection. Such a legal–policy linkage is also conducive for promoting integrated water resource management. Notably the legal aspect of water rights has multiple linkages with many other legal, policy and administrative aspects. Similarly, the policy aspects pertaining to user participation, management decentralization and private sector participation have strong linkages in terms of the ability to tap user support, fresh skills and private funds while, at the same time, contributing to devolution and debureaucratization.

Water Institutional Environment

Since institution–performance interaction in the context of water resources occurs within an environment characterized by the interactive role of many factors outside the strict confines of either water institutions or the water sector, institutional linkages and their performance implications are also subject to exogenous and contextual influences. The water institutional environment depicted in Figure 1.2, although not fully comprehensive, can enable us to conceptualize some of the pathways of these influences. Figure 1.2 has two analytical segments. The first captures the interaction between water institutions and sector performance; the other captures the general environment within which such interaction occurs. From the perspective of institutional change, the two segments represent, in fact, the two main sources from which the actual pressures for reform originate and are ultimately reflected in various media. Obviously, the first segment represents endogenous sources of institutional changes conveyed largely through economic, hydrological and institutional media whereas the second represents the exogenous sources of change conveyed mostly through social and political media.

Figure 1.2 also provides a context for contrasting the narrow approach to institutional change focused exclusively on institution–performance interaction with a broader approach focused not only on such interaction and its larger institutional context but also on the strategic role of the internal dynamics within the water institutional structure itself. As a result, the broader approach can deal with institutional change both from institutional and political economy perspectives. In this approach, therefore, the context of institution–performance interaction is as important as the internal mechanics of such interaction because of the conditioning effects of exogenous factors. In many instances, the context can even better explain why similarly structured water institutions can be responsible for different water sector performance. In fact, recent international case studies show that exo...