![]()

1

Introduction

Varieties of financial crisis

Financial crises are dramatic events. When they emerge, they tend to dominate the attention of the press and become the focus of policymakers. In one form or another, they have affected the lives of millions of people throughout the world. As references to sixteenth-century Dutch tulips, eighteenth-century South Seas merchant ventures, or 1920s Florida real estate make clear, they have been around for a long time.1 At their worst, such as in the cases of the Great Depression or the contemporary Great Recession, their effects have been felt worldwide, with the number of people affected counted into the billions. They have at times changed the course of history.

It is undoubtedly true that crises tend to share many common elements, rooted in specific aspects of human nature and in the characteristics of financial transactions.2 However, the evolution of financial crises is shaped by their contexts, and those contexts change over time as the international economy becomes more or less integrated in the trade of goods and services, as well as of financial assets, among residents of different countries, as exchange rate regimes and policies toward the financial sector evolve, as financial innovation takes place, as new countries engage with the international financial system, and as that system evolves new institutions to manage international economic relations.

The past 30 years have witnessed substantial evolution along all of these dimensions. The term “globalization” has become the catchphrase for what the world economy has experienced during the past two decades of the twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty-first. Not only has trade grown intensely among advanced economies, but developing economies have participated more intensely in international trade as well, not just in their traditional roles as exporters of commodities, but as major exporters of manufactured goods and participants in international production chains. Technological improvements in communications and information processing have broken down some of the barriers of asymmetric information that impaired the movement of financial capital across international borders, and such movements have also been facilitated by institutional innovations in advanced-country financial sectors that have given rise to non-bank financial institutions eager to identify investment opportunities outside their own borders.

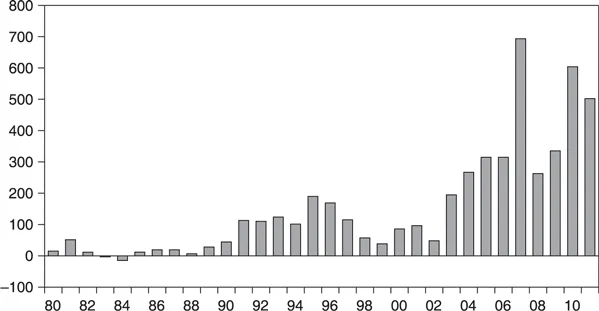

However, the process of international financial integration has been neither universal nor smooth. Advanced economies, with long-established market-friendly institutional frameworks, relatively stable macroeconomic environments, and an abundance of creditworthy borrowers, had only to remove legal restrictions on capital movements imposed during the Great Depression, a process that began in many such countries in the 1970s, to begin to integrate themselves together financially. None of these favorable elements was present in most developing countries at the time. By the late 1980s, however, a significant number of developing countries had simultaneously reformed their policy regimes to take greater advantage of market mechanisms and had reoriented their macroeconomic policies to achieve more macroeconomic stability, especially in pursuit of lower inflation. At the same time they became more receptive to foreign capital, and removed many of the legal restrictions that, together with poor information flows and low levels of creditworthiness, had created strong impediments to international north – south capital movements. Chile, an early developing-country reformer in the late 1970s, led the way. The result, as shown in Figure 1.1, has been several major waves of capital flows from private lenders in advanced economies to private borrowers in creditworthy and financially open developing ones – countries that have come to be known as “emerging” economies, reflecting this enhanced degree of financial integration. This process continues as progressively more developing economies continue to “emerge.”

Figure 1.1 Private capital flows to emerging and developing economies, 1980–2011 (US$ billion)

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database, October, 2012

Unfortunately, the process of international financial integration has faced many bumps in the road over the past 30 years, in the form of severe financial crises in which the movement of financial capital across international boundaries has played a major role. These crises have affected both advanced and emerging economies. This book is about some of the bumps along the road to international financial integration during this time. The crises that have punctuated this process have received a substantial amount of attention from professional economists. Among other things, many economists have questioned whether the repeated occurrence of such crises should raise doubts about the desirability of the very process of international financial integration.3 Views on this issue, both among academic economists as well as in the international policy community, have tended to fluctuate over time. If, but for the vulnerability to crises, the benefits of international financial integration would otherwise be perceived as outweighing its costs, then the answer to this question must depend on whether crises are somehow intrinsic to the process of international financial integration, or whether there is hope to avoid them, or at least to make them less frequent and/or mitigate their effects.

This book examines what we can learn about this issue by examining ten crisis episodes from 1980 to 2010, featuring two advanced economies and eight emerging ones. The primary objective is to understand why these crises happened, what role international capital flows played in their evolution, and why capital flows played the roles they did. A secondary objective is to learn what determined the severity of these crises, and what roles were played by policy – both domestic policy as well as policy actions by the international community – in mitigating or aggravating their effects. Were these crises exogenous events with some probability of afflicting any country that opens itself up to international financial integration, or were they self-inflicted wounds that are in principle avoidable in the future by learning from the mistakes of others?

1.1 What is a financial crisis?

The term “financial crisis” is widely used, but rarely defined precisely. It has been applied to a wide variety of macroeconomic maladies, many of which share few obvious similarities except the perception that something has gone terribly wrong with the economy at the macroeconomic level. Since this is a book about crises, defining precisely what we mean by a “financial crisis,” a term that can be (and has been) applied to all the episodes covered in this book, is a good place to start. I will define a financial crisis in somewhat abstract terms as a situation in which the credibility of some economic agent’s (or agents’) commitment to discharge a financial obligation that that agent has previously undertaken is called into question by the market – that is, by other economic agents who have come to rely on that commitment.

Financial obligations take the form of commitments to exchange financial assets for each other on preannounced terms. Such commitments can be undertaken by a wide variety of economic agents, but a macroeconomically relevant “crisis” materializes only when a previously existing commitment made by a macroeconomically important agent, such as a government, a central bank, or a significant portion of the economy’s private financial system, is called into question. Doubts about the agent’s fulfillment of its financial commitment can arise because the agent is perceived either as unable to meet its obligations, or as unwilling to do so. Typically, this is the result of an unforeseen change in the economic environment in which that agent operates, or of the revelation of some previously unknown information about the agent’s circumstances.

Why does this create a crisis? At bottom, it’s because commitments to exchange financial assets at par sustain the relative values in the marketplace of the assets being exchanged, and the abrogation of such commitments thus raises the prospect of sudden discrete changes in relative asset prices. Such large discrete relative price changes in turn create the potential for large redistributions of financial wealth, and therefore create incentives for massive portfolio reallocations away from the assets that are expected to lose value and into those expected to gain value, before the relative price changes actually materialize.

1.2 Varieties of financial crisis

Financial crises can take many forms, depending on the identity of the agent or agents whose financial commitment is called into question and on the relationships among the financial circumstances of different types of economic agent. In this book I focus on three different types of “pure” financial crisis:

1 a currency crisis arises when a central bank’s ability to redeem its notes for foreign exchange at par comes into question

2 a sovereign debt crisis arises when a government’s ability or willingness to retire its debt (i.e. to exchange it for legal tender) according to originally contracted terms comes into question

3 a banking crisis emerges when a significant portion of a commercial banking system’s ability to redeem its deposits for currency at par comes into question.

1.2.1 Currency crises

Among these three, currency crises have probably received most attention among macroeconomists. The literature on this topic has progressed through a succession of “generations” – families of analytical models sharing common features – reflecting the economics profession’s deepened understanding of the possible causes of currency crises based on experience.

First-generation crisis models date to the seminal work of Krugman (1979) and Flood and Garber (1984). These models emphasized mechanical policy inconsistencies at the central bank, in particular between exchange rate and monetary policies, in the presence of a high degree of financial integration. In the canonical case, the central bank announces a fixed nominal exchange rate, but allows the stock of domestic credit to grow more rapidly than the demand for money.4 Because the capital account is open and the exchange rate is fixed, the private sector can prevent the central bank’s credit expansion from increasing the money supply faster than the private sector’s demand for money by the simple expedient of converting domestic currency into foreign assets through capital outflows. The central bank is obligated to make this conversion by its commitment to keep the exchange rate fixed. To do so, it progressively depletes its foreign exchange reserves. When the central bank’s stock of foreign exchange reserves reaches a lower bound (the level of which is unexplained in the canonical model), the bank stops intervening in the foreign exchange market and allows the currency to float. The beauty of the Krugman–Flood–Garber model is the demonstration that the collapse of the fixed exchange rate regime comes with a bang rather than a whimper – the fixed exchange rate collapses in a sudden speculative attack that drives the central bank’s reserve stock to its lower bound in a discontinuous fashion. This must be so because, assuming an unchanged central bank monetary policy after the regime transition, a discontinuous jump in the exchange rate that would involve capital losses for agents holding the domestic currency can be avoided only if the money supply drops discontinuously, instead, as the result of a speculative attack that drives the central bank’s reserves to their lower bound. Since the central bank’s behavior is assumed to be widely understood, speculators have an incentive to avoid such losses by attacking the currency at exactly the time when doing so would prevent a jump in the nominal exchange rate.

It is important to note that, despite the dramatic behavior of speculators in first-generation models, the role of capital flows is purely passive in this context. The exchange regime transition certainly constitutes a crisis as defined above, but it is not caused by capital flows in any meaningful sense. The regime transition is caused by domestic policies, and the only role of capital flows is to make the transition an abrupt one, rather than a smooth process.5 It is also true that in first-generation models the crisis is a non-contingent event. As long as the central bank’s policies are unchanged, the crisis must eventually happen.6

Second-generation models gained prominence as the result of the inability of first-generation models to explain the ERM crisis (see Chapter 3).7 While that crisis emerged in the context of fixed official exchange rates, there was no role for excessive credit growth, so the crisis could not be explained as the result of mechanical inconsistencies in central bank behavior. Instead, second-generation models emphasize optimizing behavior on the part of the central bank: the central bank’s actions are assumed to be determined so as to maximize a specific objective function, featuring some combination of macroeconomic objectives as well as objectives that reflect the bank’s own institutional goals. Adhering to an announced exchange rate parity affects the attainable value of this objective function, and the question becomes whether the function is maximized by defending the exchange rate parity or by abandoning it, by either devaluing or floating. The central bank adheres to the parity if doing so maximizes its objective function, and abandons it otherwise.

However, in some circumstances the central bank’s actions may be indeterminate in these models, and multiple equilibria may arise. Because the central bank’s objective function is affected by the state of the economy, and because the state of the economy in turn may depend on whether economic agents expect the official exchange rate parity to be defended or not (e.g. through the effects of such expectations on domestic interest rates), the outcome of the central bank’s optimizing decision may depend on agents’ expectations about the bank’s behavior. If the bank is expected to abandon the parity, its objective function may be affected in such a way that it is indeed optimal for it to do so, and if it is not expected to abandon it, then it may be optimal for it to defend the parity. In other words, agents’ expectations may be self-fulfilling. In general, whether the outcome for the exchange rate parity is determinate or not depends on the strength of the underlying macroeconomic “fundamentals” that affect the central bank’s objective function: at one extreme, if the underlying conditions of the economy are such that abandoning the parity yields very strong net benefits, then it will be rational for the central bank to do so, and for the private sector to expect it to do so. At the other extreme, if the underlying fundamentals are sufficiently strong under the existing parity, there would be no reason for a devaluation or regime change to be expected or implemented. It is in the intermediate range where the influence of expectations may tilt t...