![]()

I

Overview and a Non-Euro-American Perspective

Part I (see chap. 1) provides a brief description of the assessment-intervention process that subsequent chapters flesh out for substance, clarification, examples, and increased credibility. This model is neonate and tentative, open to a questioning of specific steps or addition of new steps, revisions, and replacement by alternative models. I hope this handbook serves to inform the model. Assessment has become part and parcel of intervention, with inextricable components fused to compose one fluid process and subject to demands for predictive validation of diagnostic and therapeutic outcomes. Chapter 2 provides an example of only one of a number of recent culture-specific perspectives critical of the efficacy of the Euro-American mental health establishment with non-Anglo clients. The perspectives of the various cultural/racial groups in the United States all differ remarkably from a Euro-American perspective, but they share common concerns with being heard and understood by the mainstream mental health establishment. Other chapters in the handbook provide vivid glimpses of Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Asian American perspectives, but these perspectives have not been articulated in detail comparable with the Africentric perspective.

Chapter 2, an Africentric perspective, begins with an examination of ethics as codified by the American Psychological Association (APA). Carolyn Payton (1994) described the 1992 ethics code as “downgrading in importance of psychologists’ declaration of respect for the dignity and worth of the individual” (p. 317) consumer of services in favor of protecting psychologists. Ethical practice with African Americans includes cultural knowledge from literature, clinical expertise predicated on culture-specific sensitivity, and diagnostic conceptualizations from experience with etic and emic tools. This vision of ethical practice and these specific objectives, although rational and absolutely necessary, were not verbalized in the 1992 code. Ethical decision making requires a process that is described by a series of steps: identification of the problem in a cultural setting, identification of potential conflicting ethical issues, consultation, and review of possible actions and their consequences. Professional and cultural competence were not distinguished in the ethical code; as a result, the umbrella for protection from harm does not cover multicultural consumers of psychological services.

By juxtaposing Eurocentric and Africentric worldviews, the magnitude of potential differences in cultural/ethnic/racial perspectives becomes apparent. What is understood by services and service delivery, by roles of providers, and the construction of reality that undergirds these client expectations differs immensely. These differences in expectations persist despite the clear understanding among many educated, bicultural individuals of the ingredients that compose establishment mental health services. However, such understanding can strengthen the desire to receive services that have a more comfortable fit with their own culture-specific expectations.

An Africentric perspective functions for self-understanding and a cultural construction of reality. This perspective is communicated by means of the seven principles of Nguzo Saba that emphasize core humanistic values and the integrity of African-American culture. These principles are elaborated in detail to provide a portrait of the cultural self, the role of the individual in society, the responsible, cooperative interface with the community and community goals, as well as wholehearted belief that community persons will cherish and foster these principles.

When ethnic or racial comparisons are made against a standard provided by the dominant or mainstream Euro-American group, the outcomes are always prejudicial and demeaning because of the erroneous assumption that the measures used are universal. Although there has been a recent history of good intentions to provide fairness in using assessment instruments, the level of intentionality on the part of the assessment establishment has not been sufficient to foster cross-cultural equivalence. The effects of racism have been cumulative across generations on Anglo as well as African Americans. Anglo Americans have not understood racism and discrimination because few have experienced a daily presence of denigration or experience expectations for a continuation of this process. A strong quality of involuntary servitude still remains when acceptability of persons who are designated non-White is predicated on assuming the values, behaviors, and affect of the mainstream Euro-American society. This recognition was the impetus for Nigrescence theories, descriptions of pathologies attending emulation of the White mainstream, and later for articulating Africentrism as a source of pride in self and group so vital to physical, mental, and spiritual health.

Reference

Payton, C. R. (1994). Implications of the 1992 Ethics Code for diverse groups. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 25, 317-320.

![]()

1

An Assessment-Intervention Model for Research and Practice With Multicultural Populations

Richard H. Dana

Portland State University

An assessment-intervention model was designed to illustrate how assessment research and practice can move in the direction of cultural competence. This model was initially proposed in a basic multicultural assessment text (Dana, 1993) and subsequently was expanded to incorporate culture-specific intervention strategies for African Americans, American Indians/Alaska Native, Asian Americans, and Hispanic Americans that contained culturally relevant components (Dana, 1998e). Whenever the format, structure, substance, service providers, and service delivery styles of interventions for multicultural clients met client expectations and conformed to their health-illness beliefs, these interventions were more likely to be accepted and responded to positively with beneficial outcomes. The history of mental health services provided by culture-specific mental health agencies had suggested many ingredients of cultural competence that were found to be credible to clients and necessary for quality care (Isaacs & Benjamin, 1991). Similarly, characteristics of agencies, programs, and personnel were identified in research literature and operationalized in an Agency Cultural Competence Checklist (Dana, 1998a; Dana, Behn, & Gonwa, 1992; Dana & Matheson, 1992). Finally, the impact of matching language and ethnicity of clients and providers was associated with increased retention rates and more beneficial outcomes of interventions for multicultural clients (Takeuchi, Sue, & Yeh, 1995). These several avenues of research and practice evidence were influential in the development of this model, as described in earlier papers (Dana, 1997, 1998c). The description offered in this chapter includes additional research evidence and cites other handbook chapters for additional documentation, illustrations, and examples.

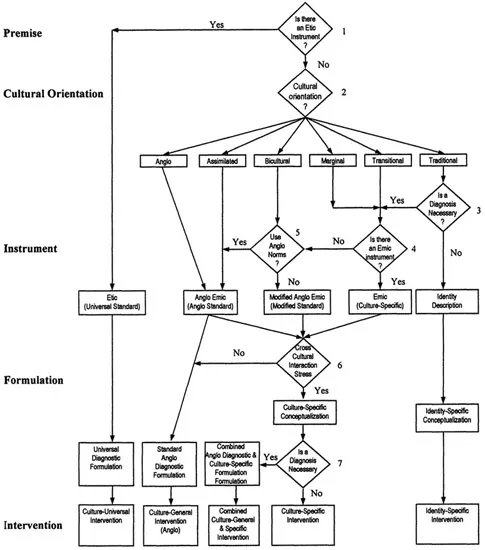

The model assumes differences in human behavior, including personality variables and symptomatology suggestive of dysfunction, on the basis of cultural identifications. Culture is considered to be of major importance unless specific cultural issues can be ruled out by information provided in the responses to a series of seven questions posed at different points during the entire assessment process (Fig. 1.1). The initial phase of the assessment process serves to establish whether the magnitude of cultural differences is sufficient to require either culture-specific modifications and/or corrections for culture in standard instruments or the use of culture-specific instruments. This information can increase the reliability of the assessment process and lead to more valid diagnostic statements. Following this model can also result in subsequent interventions that are more likely to be well received and effective. When individuals are assimilated or bicultural and cultural issues are minimal, standard assessment and standard interventions can be used to meet criteria of acceptability and fairness. However, the presence of cultural self-identification and/or presenting issues related to culture, ethnicity, or race suggests that standard services may be ineffective and should either be applied with caution or not used at all. Instead, culture-specific interventions should be provided, if available, or referral to another provider for these services may be necessary.

Premise

The model begins with the premise that universal or culture-general instruments called etics may become feasible in the future but are not sufficiently developed at the present time for meaningful applications in clinical assessment practice. The initial question pertains to the availability of these etic instruments, and the answer is negative. There has been a prolonged search for universals, and a taxonomy of possible psychological universals is available (Lonner, 1980), but there are few genuine etic tests available for clinical assessment purposes. If these etics were available, their use would lead to an etic diagnostic formulation and interventions that were culturally universal, as Fig. 1.1 indicates. Similarly, culture-specific or emic instruments were developed historically for research purposes and more recently for clinical assessment. A combined etic-emic approach for use with particular constructs has been suggested (Triandis et al., 1972) and applications have been completed (e.g., Davidson, Jaccard, Morales, Triandis, & Diaz-Guerrero, 1976; Triandis et al., 1993). In chapter 18, Ephraim describes another etic-emic rationale developed by De Vos for cross-cultural interpretation of the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) that has stimulated interesting research. It provides clinical examples for sensitization of students to the potential of this approach for understanding persons from many countries. Similarly, in chapter 12, Holden presents several newer tests for personality and psychopathology that have potential as genuine etics, but their status as etics is neither sufficient nor conclusive at present.

FIG. 1.1. Multicultural assessment-intervention model.

Cultural Orientations

The second question in Fig. 1.1 invokes culture specifically by asking for information concerning the relationship between an original cultural identification and acculturation to a host culture. I have suggested the cultural orientation status categories of traditional, marginal, bicultural, and assimilated included in Fig. 1.1 (Dana, 1992). A transitional category for American Indians/Alaska Natives contains bilingual persons who question traditional values and religion (LaFromboise, Trimble, & Mohatt, 1990); it is also included in Fig. 1.1 together with a sixth orientation, Anglo. These orientations are nominal categories for providing a reasonably good fit between clients and tests. Four of these cultural orientations are similar to those developed by Berry (1989) in response to questions of the relative value of maintaining cultural identity and relationships to other groups. These acculturation outcomes have been measured in linear terms as the extent of transition from a traditional cultural orientation status to an assimilated status. However, most recent research has focused on the development of two separate and independent or orthogonal scales measuring psychological activity for each culture to provide an index of balance between two cultures. In chapter 6, Cuellar indicates that linear measures are limited in the amount of information provided about personality constructs and acculturation while orthogonal measures can generate additional information including two types of bicultural individuals. Cuellar also provides a selected chronology of acculturation/ethnicity measurement between 1955 and 1995. Sodowsky and Maestas have an appendix in chapter 7 describing non-Hispanic acculturation and ethnic identity instruments. An examination of major Hispanic acculturation instruments is also available (Dana, 1996). Burlew and her colleagues review and describe racial identity measures for African Americans in chapter 8. Good psychometric measures of acculturation now exist in abundance for a large number of cultural groups, but practitioners have not used them routinely in clinical assessment. The APA ethics committee provided a negative response to the published recommendation that acculturation evaluation was an ethical necessity (Dana, 1994).

Acculturation information in response to Question 2 has several major uses: (a) determine the suitability of standard tests, with or without modifications, for multicultural clients; (b) help in developing cultural formulations for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed. [DSM-IV]); (c) encourage an examination of the contents and boundaries of the cultural self; and (d) provide some of the ingredients for culture-and identity-specific conceptualizations leading to culture- and identity-specific interventions. This information can be gathered using linear and/or orthogonal scales and by judicious use of interview content. Although there have been many single-item, several-item, or brief instruments developed for research purposes, these research tools are not suitable for clinical assessment purposes because the information provided may not be reliable and leads to a label rather than a selection among cultural orientation status categories. Research to identify salient components across instruments suggests that these consensual items may eventually be used in an interview format to evaluate cultural orientation status. However, only the item selection and analysis phase of research has been completed (Tanaka-Matsumi, 1998). The information resulting from Question 2 is used to determine selection or modification of the instruments used in assessment.

Cultural formulations and conceptualizations for purposes of diagnosis or intervention require considerably more detailed knowledge of culture. Question 3 pertains to the necessity of diagnosis. If a diagnosis is not required (e.g., when identity problems are presented), then an identity description can lead to an identity-specific conceptualization as the basis for an identity-specific intervention (e.g., Phillips, 1990; Ruiz, 1990). Additional information may be required from culture-specific tests. In chapter 24, Morris includes a listing of African-American emics described in detail in edited volumes (Jones, 1996).

Whenever a diagnosis is required, the DSM-IV outline for cultural formulations (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) calls for information in five areas, including cultural identity, particularly from orthogonal instruments that describe involvement with the culture of origin and the host culture as well as language abilities and preference. A cultural explanation of the individual’s illness contains idioms of distress, the meaning and severity of the illness described using cultural reference norms, and any local categorization for illness as well as causes and explanations. Cultural factors related to the psychosocial environment and levels of function as well as cultural elements in the relations with the clinician are also included. The outline concludes with an overall cultural assessment for diagnosis and cure. Chapters 25 and 26 describe the preparation of cultural formulations and present examples (e.g., Hispanics and American Indians/Alaska Natives). As these chapters suggest, providing this information entails in-depth cultural knowledge and may require an emic instrument for supplemental content whenever available (see Question 4). There are relatively few emic instruments at the present time, except for African Americans, as noted earlier. However, some emic instruments for several different populations have been developed to measure acculturative stress. Examples include the Hispanic Stress Inventory (Cervantes, Padilla, & Salgado de Snyder, 1991); the Societal, Attitudinal, Familial, and Environmental Stress Scale (Chavez, Moran, Reid, & Lopez, 1997); and the Cultural Mistrust Inventory (Terrell & Terrell, 1981) recently used by Whaley (19...