![]()

Chapter 1

Drinking and Driving in the United States: The Scope of the Problem

INTRODUCTION

Driving under the influence of alcohol has been a major social problem ever since the automobile came into popular use. It has been of worldwide concern for almost 100 years. The contribution of alcohol to increased risk of traffic accidents has been well established. Experimental studies and epidemiological surveys, conducted in a number of industrialized countries since the early part of this century, have documented consistent and reliable evidence of the correlation between alcohol consumption, increasing blood alcohol concentrations (BACs), and the increasing risk of involvement in an alcohol-related road accident. The recognition of the importance of alcohol-related road traffic accidents as a significant cause of mortality, disability, and economic loss has focused international efforts on the development of policies and strategies for the prevention of injuries and fatalities. Public concern in the United States has increased dramatically since the 1980s, resulting in a concerted attention at national and local levels to reduce the rates of drunk driving in our society. With the “get tough” attitude prevalent since the 1980s, great strides have been made in reducing the incidence of drunk driving. However, the rates are still unacceptably high. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), the agency responsible for overseeing highway safety issues in the United States, has set a goal of reducing annual DWI fatalities to 11,000 by the year 2005. However, the problem of drunk driving has proven to be a stubborn one that does not easily give way to solutions. The number of DWI fatalities for 2000 was 16,068. Recognition is growing worldwide for the need to address the issue of those drinking drivers who do not respond to sanctions and treatment, but continue to drink and drive even when facing severe consequences. This population causes a disproportionately large percentage of alcohol-related injuries, property damage, and fatalities compared to other drivers. More emphasis is being placed on the development of improved intervention strategies aimed at the drinking driver who is a high-risk problem drinker, a high alcohol consumer, and a chronic multiple DWI recidivist. Researchers and treatment experts in the alcohol and drunk driving field recognize that current intervention policies need to be modified in order to better address this “hard-core” population.

Deaths caused by drunk drivers are the most tragic aspect of this problem. Drunk driving threatens the lives and well-being of drivers, passengers, and pedestrians, whether they have been drinking or not. The drunk driver is most commonly portrayed in the media as a seriously alcohol-impaired individual driving out of control and causing fatal car crashes. This image misrepresents the true extent of the problem. The reality is that people of all types and of all backgrounds drink and drive for a variety of reasons. A growing body of research indicates that even low amounts of alcohol contribute to highway fatalities. From a sociological perspective, many of the ceremonial and institutional functions in our culture influence decisions to drink and drive. Examples of these activities are weddings, sports events, certain holidays, bar mitzvahs, bachelor parties, celebrations, and ceremonies. Other situations can be special events, such as family reunions, birthdays, farewells, and work-related social events. These types of drinking situations most frequently take place in the community, where the use of an automobile and driving after consuming some amount of alcohol is often involved.

When defining the impaired driver, we tend to identify those who drive above the legal threshold as the problem driver. It has been assumed that that those who are driving above the legal threshold are intoxicated, and those who are driving below that threshold are not impaired. This dichotomy oversimplifies the DWI population. It is more useful to view the drinking driver along a continuum that extends from the low-risk to the high-risk driver.*

Through worldwide efforts and experiences, much has been learned about this complex problem. Improved research techniques provide us with newer and better understandings so that more effective, efficient, and comprehensive strategies can be developed. More is known about the relationship between alcohol intoxication and driving than about any other drug. We have learned much about drinking and driving, but we still have much more to learn.

HISTORY OF THE DWI COUNTERMEASURES MOVEMENT

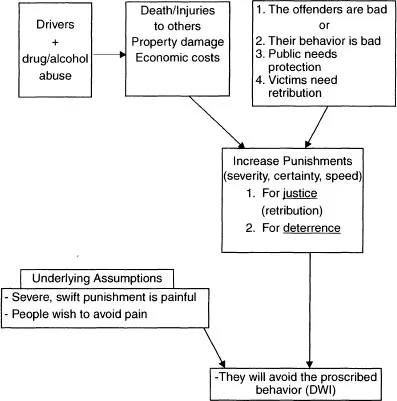

The relationship between automobile crashes and excessive alcohol consumption has been long recognized as a problem. A classic editorial concerning “motor wagons” appeared in the Quarterly Journal of Inebriety in 1904. Initially, when this problem became evident, it was only vaguely understood. Lawmakers attempted to control drinking and driving solely by legal means. Legal punishment is a cornerstone of social control policy. The main tenet of this policy holds that punishment will deter citizens from engaging in an illegal act. In the early part of the century, the “Punishment-Response Model” was the primary deterrent action used to control the problem of drunk driving. Law enforcement was utilized as the primary mode of countermeasure for this problem. Penalties for this act were based on criminal law (see Figure 1.1). The focus of the law, referred to as “classical” (Ross, 1982a), had been on the grossly intoxicated driver. Laws prohibiting driving “while under the influence of intoxicating liquor,” driving in an “intoxicated condition,” or “drunk driving” targeted the unacceptable act of being intoxicated and driving an automobile (Fischer and Reeder, 1974, p. 173). During this classical period, obtaining a conviction when the impairment did not result in a crash was difficult. Plea-bargaining and settling out of court were often-used strategies to delay, reduce, or avoid legal consequences.

FIGURE 1.1 The Punishment Response Model

Source: Adapted from Robbins, L., National Commission on Drunk Driving, 1986.

Social science theory holds that the “efficacy of the legal threat is a function of the perceived certainty, severity, and celerity of punishment in the event of a law violation” (Ross, 1982a, p. 27). Early experience has shown that significantly increasing the threat of punishment for drinking and driving did reduce alcohol-related crashes. However, over time, drinking-driving problems would return to previous levels. The reasons for this phenomenon were not clearly understood. This was a universal experience in countries adopting anti-drunk-driving laws. It appeared that legal interventions were not achieving their expected outcome. Deterrence-model researchers attempted to better understand this phenomenon by studying variables impacting the efficacy of the model. Classical laws were not established with the intent of providing “certainty, severity, and celerity of punishment” as is necessary for deterrence to be effective. Based on these experiences, and the conclusions of research, it was apparent that changes needed to be made in the way the law was written. As a result, in 1936, the Norwegian Parliament established new types of drinking and driving laws, in an attempt to improve the effectiveness of deterrence measures. These laws appear to follow the principles of deterrence theory more closely. Provisions were made in the law to increase the likelihood of apprehension, conviction, and punishment. These laws, almost unchanged, are still in effect today. One significant change in the Norwegian laws centered on redefining the rules of proof of intoxication. Intoxication was now based on a scientific legal standard through the use of a fixed measurement of the quantity of alcohol in the bloodstream. Laws were written to include a presumption that all drivers above this level are intoxicated (per se is the legal term used to designate this presumption). A conviction could now be obtained per se, regardless of the drivers’ performance at the time. A blood alcohol level of 50 milligrams per 100 milliliters of blood (.05g/dl) was considered proof of intoxication. As a result of establishing a scientific legal standard of intoxication, convictions were easier to obtain. Conviction rates increased, thereby increasing the certainty of punishment. With this change, the emphasis shifted from having to prove intoxication to determining whether a driver has a certain amount of alcohol in the bloodstream.

Sweden followed Norway’s example in 1941 with the establishment of blood alcohol levels as proof of intoxication. They created a two-tier system of punishment based on two different blood alcohol levels. These changes in law formed the basis for what is known as the “Scandinavian Model.” Norway and Sweden also developed serious punishments, which included imprisonment for severe cases, heavy fines for the less severe, and immediate license suspension pending trial. Norway and Sweden, which had already established roadblocks as a usual means to check on licenses and registrations, now included blood alcohol levels as part of these checks. World War II interrupted this momentum, and it was not until the 1960s that the movement regained its momentum and spread to other countries. Recognizing the effectiveness of these measures, other Western countries rapidly began to adopt the Scandinavian model. By 1970, Great Britain (1967), New Zealand (1967), Australia (1968), Canada (1967), and the United States (1966) had adopted the Scandinavian model. In the 1970s, the Netherlands (1974), France (1978), Denmark (1976), and Finland (1977) also adopted variations of the Scandinavian model.

Though punishment is seen as an important aspect of the criminal law system, rehabilitation is also a primary goal. As classic laws gave way to more modern intervention techniques, treatment became an important component in the attempt to control drunk driving. Germany has a long history of requiring DWI offenders with BACs of .13g/dl and higher to be evaluated for fitness to drive by medical/psychological experts before being relicensed. First offenders are generally referred to a driver improvement program. Sweden requires a medical certificate before license reinstatement. Any driver with a BAC of .15g/dl or higher is considered to be a problem drinker. After a twelve-month revocation period, a driver must continue to report for regular examinations for another eighteen months. Although it was generally viewed that mandating someone into treatment does not as a rule achieve the results intended, many theorists felt that the drunk driver would be highly motivated to rehabilitate in order to maintain driving privileges.

The treatment of the drunk driver has gone through a number of changes over time. Initially, in the Scandinavian model, treatment consisted of educational programs. As the treatment field became more experienced with this population, it underwent many modifications. Today, the European approach being adopted in many countries includes thorough medical/psychological assessment, selection and matching of offender to treatment, license reinstatement as an incentive to treatment, and follow-up provision after program completion.

Changes in the way the United States addressed the problem of drunk driving began in the 1960s. A number of developments occurred that resulted in modifications in the way the DWI problem was addressed in the United States. In 1964, Borkenstein and colleagues established the relationship between increasing alcohol levels and the likelihood of a car crash. The conclusions drawn from this research opened the way for classifications of drunk drivers who were problem drinkers, non-problem drinkers, and heavy social drinkers, as well as alcoholics. Psychometric test results were studies with the goal of being able to differentiate problem drinkers and alcoholics. This led to the later development of the Mortimer-Filkins Test at the University of Michigan in 1973. At the University of Vermont, studies were conducted on information gathered from convicted DWI offenders. Increasing efforts were made to identify the high-risk driver prior to the occurrence of a fatal crash by studying the population and developing drunken driver typologies.

Due to these efforts, increasing governmental concern led President Johnson to sign the Highway Safety Act of 1966. This act established the National Highway Safety Bureau, which is now the National Highway Safety Administration (NHTSA), under the Department of Transportation. The Secretary of Transportation was empowered to direct, assist, and cooperate with other Federal Agencies, state and local governments, and private industry to increase highway safety. Each state was to establish and develop a highway safety program designed to reduce traffic accidents, deaths, injuries, and property damage. The Secretary of Transportation was mandated to study the relationship between alcohol and accidents. Federal penalties were applied to states that did not comply. Laws, enforcement methods, treatment of alcoholism, and other policies were to be reviewed and studied in order to improve highway safety.

The roots of the DWI treatment field in the United States began as an outgrowth of this action. In 1966, the Phoenix Program was established. These programs were based on those developed as part of the Scandinavian model. These programs provided education and referral to treatment for DWI offenders. They consisted of four two-and-a-half-hour weekly sessions. Included in the content of these programs were informal structured discussions, films, readings, and oral and written exercises. An instructor conducted the sessions with a probation officer in attendance. A municipal judge would attend the initial session, and would describe the court’s role in this program. Counselors were present to make referrals for treatment if necessary. These were considered diversionary programs, so that those attending would not be charged with the offense if they successfully completed the program.

In 1970, the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA) was established with the enactment of the Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation Act. The Department of Transportation, as a follow up to the Phoenix Program, funded the Alcohol Safety Action Program (ASAP) in 1971. ASAP goals were aimed at expanding the use of alcoholism treatment programs for people with alcohol problems, increasing public awareness through education, and evaluating, diagnosing, and referring for treatment. They established thirty-five pilot programs in designated states throughout the...