![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to Ministry in Hospital Settings

Sometimes situations come along in our lives that give birth to compassion. But one can also be more deliberate. Intentionally placing oneself in situations where people are struggling and need help, and being present to that experience, can be transformative....What matters for this means of transformation is letting the life circumstances of others move one’s heart. (Borg, 1998, p. 127)

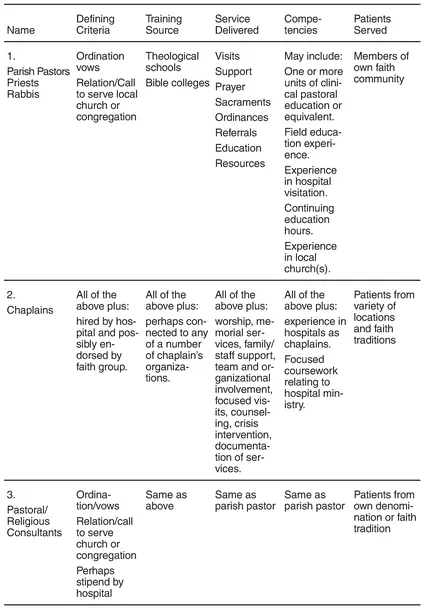

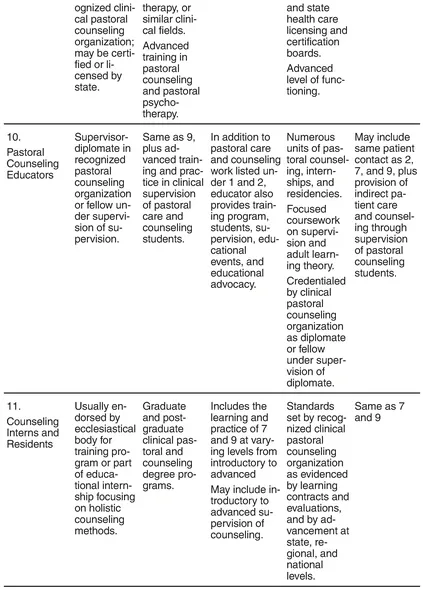

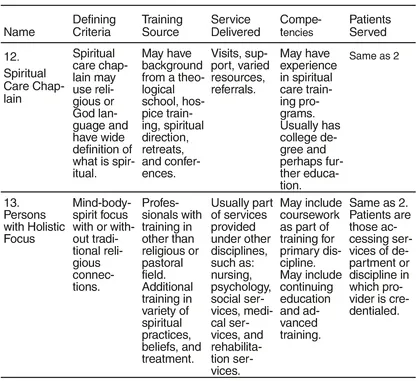

Recently, as I began thinking about this first chapter of the book, I spent the better part of a week trying to identify the various names, affiliations, types of training, and focus of services for persons engaged in hospital ministry. I was surprised to settle on thirteen categories to include in this chapter. Once these categories were chosen, it was a logical step to group them into larger categories, and then into three major classifications of traditional ministries, newer traditions, and recent directions. The newer traditions were further divided into two sections: clinical pastoral education and clinical pastoral counseling (see Tables 1.1-1.4).

This categorization of people, functions, skills, and services is intended to bring increased clarity to a field that is becoming more diverse. The increased categories of hospital ministry have brought new directions and challenges that are discussed later in this chapter. In efforts to use this information, readers may wish to reflect on their own ministries and the challenges faced. For those who wish to review their ministry or department using this format, a blank form is provided in Appendix A.

TABLE 1.1. Hospital Ministries, Traditional

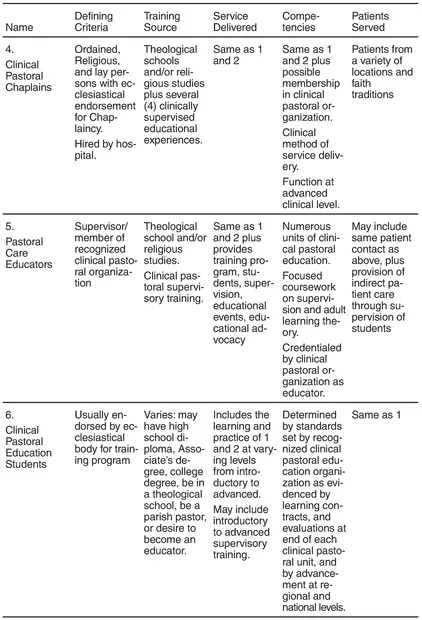

TABLE 1.2. Hospital Ministries, Newer Traditions: Clinical Pastoral Education

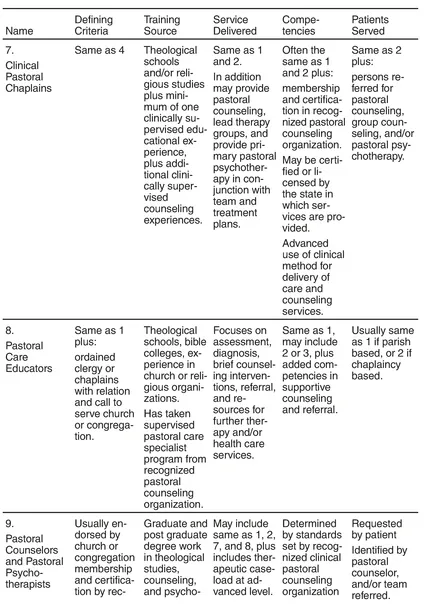

TABLE 1.3. Hospital Ministries, Newer Traditions: Clinical Pastoral Counseling

TABLE 1.4. Hospital Ministries: Recent Directions: Postmodern Spirituality

Traditional Ministries

Parish Pastors, Priests, Rabbis, and Others

Clergy who view hospital ministry as visitation of the sick are included under traditional ministries, as Table 1.1 illustrates. Visitation is offered as part of one’s clerical duties, or as a self-chosen interest. This category consists of parish pastors, priests, rabbis and persons of religious orders. This is a large category since leaders from most major religions undertake hospital visitation when someone from their own faith community is hospitalized.

Since Jewish and Christian biblical times, visitation of the sick has been an expectation of family and community members, churches, and congregations. Quite early on, the role of visitation was also assigned to compassionate and willing deacons and elders. As hospitals came into being, patients were often moved from home to hospitals when illness fell upon them. Clergy were then given the task of visiting sick members of their congregations in the hospital. This visitation continued, even in situations where lay visitors and elders made hospital calls. Today, community clergy continue to provide the bulk of visitation and spiritual care services in many hospital settings where patients associated with their faith communities are hospitalized.

Chaplains

Many hospitals today have a long-standing tradition of providing chaplains who meet job expectations as established by individual hospitals. These requirements are often influenced by established standards of specific faith groups such as ordination and/or ecclesiastical endorsement. Some of these chaplains may also rely on “on the job” training in their new positions.

Example

At New Hampshire Hospital, an acute care psychiatric facility, the transition to hiring community clergy to provide services to hospitalized patients took place by 1856. Prior to this time patients were often free to attend worship services in the town of Concord. As treatment styles changed, the patients were less free to move from the hospital to the community on a daily basis. Thus, community clergy-chaplains brought these essential services to the hospital. Visits were conducted and worship services were held in an auditorium, and later, were held in a full-size chapel in the main hospital building.

Right through the 1950s, chaplains lived on hospital grounds and provided services day and night. Having chaplains on staff meant greater availability of services to persons throughout the state of New Hampshire who were often far away from their regular faith communities, and, through choice and the vicissitudes of isolative events that often come with mental illness, were no longer connected to faith traditions in their hometowns. All of these factors led to growth in the tradition of providing Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish chaplains at this hospital. An interesting by-product of these changes was the growing number of patients and former patients who no longer identified with a specific Catholic, Protestant, or Jewish congregation, but rather with the hospital chapel and ministry.

Pastoral/Religious Consults

Another category of clergy who provide hospital ministry came into being partly as a result of the use of paid chaplaincy services. Although hospital chaplains at that time were accountable to their churches and hospitals, they were usually Protestant, Catholic or Jewish. Still, many faith traditions had no specific representation in hospital chaplaincy services. To serve these patients, chaplains needed to broaden their perspectives and focus of their services, and determine when it would be essential to bring in consults from other specific faith groups. Often these pastoral/religious consults would be Mormon elders, Orthodox priests, or clergy from other church traditions such as Christian Scientists or Seventh-Day Adventists. Consults were provided on voluntary and reimbursed bases. The focus of their service was narrow, and consisted of responding to specific referrals. In situations and times when communities had clergy who were willing to engage in crisis services, the consult service went smoothly. When clergy were not willing to take referrals nor engage in this form of hospital ministry to nonparishioners, difficulties would often be experienced by the hospital, chaplains, and patients.

Traditional Ministries Today

The defining criteria for traditional ministries today remain ordination or vows of clergy/chaplains who are engaged in hospital ministry and their relation to specific churches and congregations. Sources of training often include theological school and perhaps religious orders for those who have taken vows of service. Services provided are generally supportive and pastoral, and may include worship and sacraments or provision of ordinances. These traditional hospital chaplains, or consults, are deemed competent if they serve a church, have some experience in hospital ministry, and perhaps some clinical pastoral education, which is valued and available. Competency in this form of ministry is based on a church credentialing process.

Newer Traditions

Clinical Pastoral Education

Newer traditions in hospital ministry are listed in Tables 1.2 and 1.3. These ministries grow out of two types of clinical training and two service foci. The first professional style and affiliation comes from advanced training known as clinical pastoral education. These groups are traced back to the experiences and use of trained chaplains begun by Anton Boison, who was hospitalized with a mental illness in the early part of the twentieth century.

In this clinical pastoral care training model, students and chaplains use clinical methods of learning and provide pastoral care services based primarily on an action-reflection process. A focus on the developing identity of the pastoral person is integral to the training process. Training also includes mastering the ability to define presenting problems; noting biopsychosocial and spiritual histories; assessing individual needs; and developing pastoral care plans.

Clinical Pastoral Chaplains

Chaplains trained in these clinical pastoral care methods are able to take advanced units and specialize in general as well as specialized pastoral care ministry. It is typical for many hospitals to seek chaplains who have successfully completed four or more clinical pastoral care units. Clinical pastoral care chaplains can be ordained, religious, or laypersons, and are normally endorsed for hospital ministry by their faith tradition. Their basic training usually consists of religious studies, and perhaps a masters degree from a theological school. However, their defining criteria for ministry is successful completion of several supervised clinical pastoral ministry experiences. This competency is attested by their membership in a clinical pastoral organization such as the American Association of Clinical Pastoral Educators, and by their ability to function at an advanced clinical level.

Pastoral Care Educators

Pastoral care educators are those who have advanced clinical pastoral education training, and have completed supervisory training levels to become supervisors of clinical pastoral education departments. Their training level is the same as clinical pastoral care chaplains, but carries an added focus on the supervision and running of an accredited clinical pastoral education program in a hospital facility. As with the clinical pastoral care chaplain, educators can be ordained, religious, or laypersons, and usually have a masters degree in religious or theological studies. It is the tradition once a chaplain becomes a pastoral care educator, for him or her to stop or limit the provision of direct pastoral care and shift fairly extensively to the training of students. Frequently, the educator performs much of his or her clinical work indirectly through the supervision of students.

Pastoral Care Students

The final category in the clinical pastoral education tradition is that of “student.” Students are mentioned because it is common to find them delivering pastoral care services directly to patients in hospitals, where such education programs exist. In fact, this is one of the benefits hospitals receive from participating in clinical pastoral education programs. Many students attend theological school and work on initial competencies appropriate to nonordained persons in the midst of masters level training while also working at the hospital. Their levels and capacities may change as their training progresses. In some cases, students move through the clinical training program with the sole intention of becoming educators and/or chaplains. Even more frequently, students are taking one clinical unit as required for ordination. The defining criteria, for students, is that they are engaged in a training program and are at the hospital to learn how to perform hospital visitation, specialized pastoral care, and/or chaplaincy.

Clinical Pastoral Counseling

The second type of clinical education in the category of newer traditions in hospital ministry, is that of clinical pastoral counseling. Pastoral counseling is an essential service that occurs in most hospital settings. It has become more recognized as clinical pastoral counseling has begun to be accepted as a competent therapy in the context of other disciplines such as clinical psychology, marriage and family therapy, Jungian analysis, and behavior therapy. Technically speaking, counseling has been a sound component of psychiatric hospital ministries for many years. However, today’s clinically trained pastoral therapists are a welcome component in many hospital settings.

Clinical Pastoral Chaplains

Clinical pastoral chaplains who are trained in the field of pastoral counseling are able to provide crisis, brief, and longer term counseling services. These services may consist of individual, family, and group therapies, and may also be provided for staff, though usually on a brief basis, with referral services used frequently. Chaplains with counseling backgrounds may be more intimately involved with treatment teams, may provide intensive spiritual counseling as a component of therapy, and may provide supportive as well as primary therapy services. As chaplains, these individuals are likely to also be engaged in other pastoral care and administrative functions of a pastoral care chaplain. They may in some cases be members of accredited clinical pastoral care organizations as well as clinical pastoral counseling organizations. The hospital benefits from chaplains trained in both fields.

Pastoral Care Specialists

Pastoral care specialist is a new term for clergy who have advanced supervised experiences and who specialize in counseling within a parish and/or as chaplains. This field recognizes the growing need for counseling assessment, diagnosis, brief, and crisis therapies, and the growing need for more sophisticated referral resources. The defining criteria in this category include ordination and advanced supervision in counseling on common issues such as crisis intervention, grief and loss, divorce recovery, pastoral diagnosis, and making referrals.

Pastoral Counselors and Pastoral Psychotherapists

Pastoral counselors and pastoral psychotherapists in hospital ministry are those who focus on counseling and therapeutic services. This focus may be to the exclusion of other pastoral care functions or as part of their total ministry. These individuals are usually licensed or certified by state boards and certified by a counseling organization such as the American Association of Pastoral Counselors. They specialize in holistic treatment and in the expertise of having been trained in a variety of therapeutic schools as well as in the spiritual components of illness and health.

Pastoral Counseling Educators

A pastoral counseling educator’s focus is on the supervision of students in pastoral counseling or other professional therapeutic fields that have a holistic focus. The pastoral counseling educator is usually a Diplomate in the American Association of Pastoral Counselors. Unless there are numerous students in a clinical program, the pastoral counseling educator engaged in full-time h...