1

Non-suicidal self-injury in childhood

Kelly Emelianchik-Key

Self-directed violence in the form of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) occurs in approximately 18% of the pediatric population worldwide (Muehlenkamp et al., 2012) and is a strong predictor of an eventual suicide attempt (Andover et al., 2012). Suicide is the second leading cause of death for children, adolescents, young adults, and adults between the ages of 10–34 years old (CDC, 2017). NSSI is considered a pervasive issue among the adolescent population, but there is limited information about self-directed violence in children under the age of 14 (which includes both suicide and NSSI). However, there is strong evidence that children as young as seven years of age are engaging in forms of self-directed violence (Barrocas et al., 2012).

Early childhood development

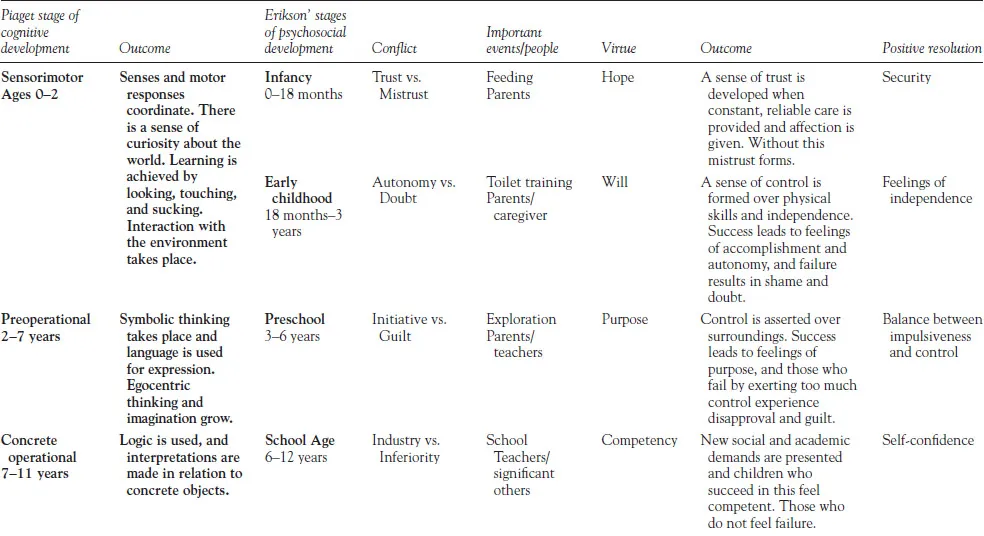

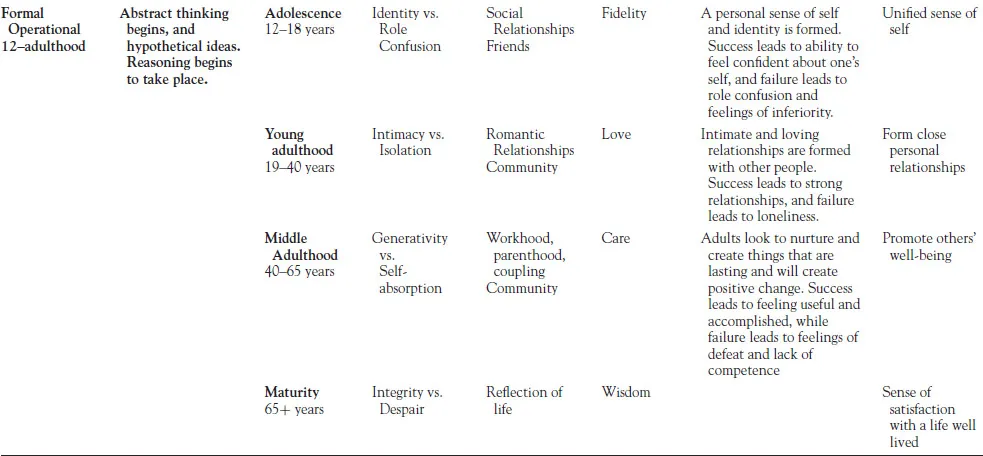

When working with younger clients who engage in NSSI, it is important to first begin by examining developmental theories and the unique role they play in self-injury onset and engagement. Developmental theories most often divide childhood through stages that are marked by quantitative differences in the child’s behavior and development. Erik Erikson’s psychosocial developmental theory (1963) is one of the most well-known developmental theories. Eight stages divide the lifespan, which focus on changes in social interaction and growth through development. Each stage is marked with challenges that people commonly face in that stage of development. If not addressed appropriately, these challenges can impair growth, possibly for a lifetime. Jean Piaget’s (1976) theory of cognitive development divides development up into four stages, which define cognitive processing by age. Table 1.1 below breaks down each of the stages. In each of the cases presented, the clients are posed with challenges that can prevent or impair their cognitive and developmental stages. When working with clients engaging in NSSI, it is critical to assess these stages. This can assist the clinician in tailoring their treatment plans and picking the most appropriate intervention strategies.

Table 1.1 Piaget and Erikson stages of development

Youth who engage in NSSI are best suited to individual and family counseling, as these are the most appropriate treatment options, given that the culture of the home is largely structured by caregivers. Being exposed to increased levels of childhood family adversity and trauma exacerbates NSSI behaviors due to the added stress and is viewed as a trigger and risk factor for adolescent NSSI (Fliege et al., 2009). The automatic functions of NSSI, such as the ability to regulate affect, self-punishment, and peer connection components, directly relate to adverse childhood experiences (Kaess et al., 2013). This further supports the involvement of family members in the treatment of NSSI in children and adolescents. In this chapter, we present two case studies involving youth who self-injure. Each case will serve to present the clinical decision-making process from assessment to conceptualization of NSSI behaviors and treatment modalities. We review cases from male and female biological sex categories because NSSI behaviors have been shown to present differently for individuals identifying as male or female, particularly in youth. Intersections of diverse experience and group identification are also explored in each case. Experiences with societal and cultural stressors linked to identity can influence the emotional experience of the individual engaging in NSSI as well as their treatment needs associated with the behavior.

Case 1.1: Case of Jenny

Jenny is a 9-year-old, multiple-heritage female. She reportedly has a good relationship with both of her parents; however, they reside in different homes in the same city. Her father identifies as bi-racial (African American and Asian), while her mother identifies as White. She has two younger siblings, ages four and two. Jenny’s parents separated two years ago and have been divorced for about six months. Jenny has a history of hitting herself and hair pulling. Around the age of six, Jenny’s parents noticed that she would bang her head on the floor and inconsolably cry when she became frustrated. They thought Jenny was having trouble with changes in the home and figured that the behaviors would pass. Then, around the age of seven (following the separation of her parents), both of Jenny’s parents noticed that her eyebrows were thinning, and she appeared to be pulling hair out of her head while she did homework, as well as on days when she moved from one parent’s house to the other. Jenny’s parents have tried different methods to stop the behaviors, but they have become increasingly frustrated. Jenny has a large group of friends at school and seems to fit in with everyone. She is popular in her peer group. Jenny’s parents say her teachers report they have not noticed self-injurious behaviors at school. Her teachers note that Jenny is a hard worker and tends to help other children in her class. She is also active in after-school soccer and seems to enjoy it. When at home, Jenny helps to watch her siblings as much as she can and tries to be caring. Jenny’s mother says that she sometimes notices behavioral problems when she asks Jenny to complete a task. Jenny can become visibly frustrated if she does not do it “just right.” Jenny visits her father every other weekend and for one month in the summer. Jenny’s dad ignores the hair pulling and expects Jenny’s mother to attend to the behavior and “make Jenny stop.” When Jenny tries to bang her head or hit herself, her father says he restrains her and punishes her. He states he does not notice the behavior as much as Jenny’s mom does and wonders “how much it really happens.” Jenny’s mom believes the self-directed violence is just part of a phase, but she frequently tries to talk to Jenny after an incident to make sure she is calm and convince her to stop the behaviors. Jenny’s parents argue quite a bit about what to do when Jenny has difficulty. Both indicate a desire to help Jenny. When asked about her self-injuring, Jenny becomes frustrated: “I’m tired of talking about this. My mom and dad need just to leave me alone. My mom is overreacting, and it’s not a big deal.”

Developmental perspective

Jenny’s behaviors began to appear at a critical age. In Erikson’s developmental theory (1963), Jenny would be in the industry v. inferiority stage. Typically, in this stage, a child’s world expands at school, and social interactions play a critical role. This stage is where children begin to feel accomplished and confident. They start to take pride in the tasks that they complete. The most impact usually comes from encouragement by adults around them, typically from parents and caregivers. Additionally, at age five, most kids begin school and enter a structured kindergarten/educational setting. This is where teachers begin to take on another critical role for children. For most children, this new atmosphere will change their normal routines. The transition to school also brings about different educational and social expectations for children. Jenny entered school around the same age that her hair pulling began. This is important to note since there were many critical factors going on at one time during this age for Jenny. Jenny built new peer relationships and has begun to gain academic expectations. This can bring about stress and anxiety for some children. Jenny needs to have a balance of encouragement and support from her teachers. She also needs to feel unconditional love and support from parents. Jenny is doing well in school, which tells us that she is getting what she needs while at school and feeling accomplished and competent as a student. This is critical for her developmentally. Additionally, working with Jenny’s school and making them aware of the NSSI behaviors can be helpful for Jenny’s treatment progress. The school can support Jenny’s parents by having specific and detailed self-injury protocols and maintaining open communication about Jenny’s behaviors. Encouraging an open dialogue with teachers and staff not only best supports the student, but also assists the school in understanding the safety concerns that exist for the student.

During the same time that Jenny began school, a new sibling was born. Upon the birth of a new child, parents typically become preoccupied with additional parenting responsibilities. Parental time with Jenny became split between her and another child. When considering developmental tasks at the onset of the self-injurious behaviors, one might consult the Eriksonian task of competency. In combination, introduction to a new school environment, adjusting to a new sibling and changes within the family dynamic, and new expectations related to academic performance and peer relationships can create significant stress for a child. During the period between ages six and eight, children usually begin to learn more appropriate ways of effectively expressing and talking about thoughts and feelings. Leading up to a phase in which emotional development becomes a greater focus for social adjustment, Jenny was consumed with changes that may have been overwhelming for her. Her inconsolable crying and headbanging evidence this assertion, as both coping strategies began at age six. These self-destructive actions are a common method for young children to display non-suicidal self-injurious behavior (Klonsky, 2007). Whereas most children this age would verbally express frustrations and emotions regarding the environmental stressors, Jenny’s method for coping is to engage in NSSI behaviors to have some control over the situation and cause more turmoil.

Another significant transition occurred when Jenny was seven, namely the separation of her parents. Divorce and separation can present a difficult transition for children, changing emotional and physical support and needs related to safety and belonging. Divorce can be a major risk factor for children, particularly related to internalizing and externalizing problems. As a clinician working with Jenny, it would be important to assess how cooperative co-parenting is going and the ways conflict is managed in relation to Jenny. Child-parent relationships are negatively affected by childhood family adversity (Hughes et al., 2004), and can be a precursor and risk factor for childhood and adolescent NSSI (Fliege et al., 2009) and other internalizing/externalizing issues (Lamela et al., 2016). At the onset of NSSI, Jenny’s parents did not seek professional assistance, nor did they directly address Jenny’s changing emotional needs related to home and school changes. During the time following the onset of NSSI, her self-destructive behaviors expanded to include hair pulling. Moving between homes and additional challenges associated with her parents’ separation appear to have overwhelmed Jenny emotionally. Her expressivity of feelings was not typically verbal or verbally processed at home and was oft...