- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Northern Counties from AD 1000

About this book

Informative, vivid and richly illustrated, this volume explores the history of England's northern borders – the former counties of Northumberland, Cumberland, Durham, Westmorland and the Furness areas of Lancashire – across 1000 years. The book explores every aspect of this changing scene, from the towns and poor upland farms of early modern Cumbria to life in the teeming communities of late Victorian Tyneside. In their final chapters the authors review the modern decline of these traditional industries and the erosion of many of the region's historical characteristics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Northern Counties from AD 1000 by Norman Mccord,Richard Thompson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

c.1000–c.1290

Chapter 1

The Early Medieval North

For these early years the scanty evidence means that there are many gaps in our understanding. In some later periods, the evidence, both primary and secondary, is so extensive that it is impossible to cover it all. For the years immediately after AD 1000, the historian is trying to make sense of a jigsaw puzzle with most pieces missing.

The North in Late Anglo-Saxon Times

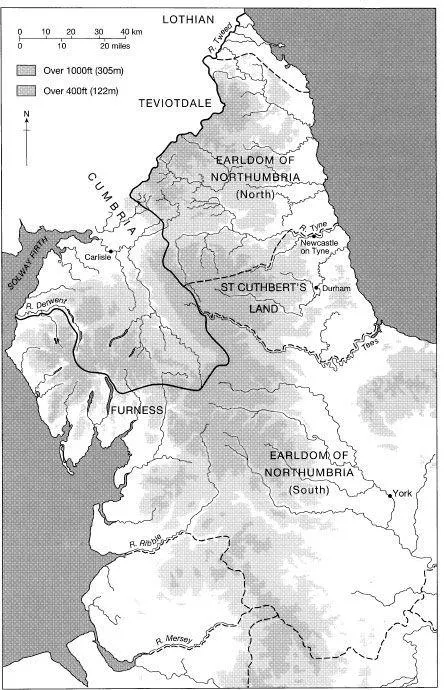

We know little of northern political arrangements during the last phase of Anglo-Saxon England. Although by this time the south and midlands of England had been welded into a reasonably coherent state, northern territories presented a different picture. In social organization, concepts of law, and structure of local authority, there remained an uncertain mixture of Celtic, Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian influences. Elements survived from earlier political entities, the kingdoms of Northumbria and Strathclyde. Scottish claims to suzerainty over Strathclyde involved demands for Cumberland which were not abandoned until the Treaty of York in 1237. Cumbria had been a peripheral dependency of Strathclyde, but the North East contained the heartland of the former kingdom of Northumbria and inherited traditions of independence which inspired resistance to both English and Norman kings. If in Northumbria conditions were far from stable, there was more homogeneity of settlement than in Cumbria. That area held an uneasy mix of settlers of British, Anglian and Norse-Irish origins, with control disputed between various neighbours. Diversity of its peoples’ origins was reflected in religious affiliations. All now at least nominally Christian, each group possessed its own saints to whom reverence was due. The northern part of the area looked to the Scottish see of Glasgow as its ecclesiastical authority, and many churches were dedicated to Celtic saints associated with that diocese. The observances associated with these cults exhibited distinctive elements of belief or superstition. The Glasgow connection was a survival of relationships established in the heyday of the kingdom of Strathclyde, and indicated that much of Cumbria was still orientated northwards.

Northern Cumbria may have remained under Scottish control after AD 1000. The southern districts, roughly those south of Shap, naturally inclined more to the English connection. (Stenton 1970) Overall, the future counties of Cumberland and Westmorland were in the eleventh century pioneer territory. They were poor, with a wet climate, much inferior acid soil, and a high proportion of forest, moorland and mountainous country. The meagre evidence indicates that extensive territorial units were needed to maintain the aristocracy. This may also have led Cumbrian leaders to supplement scanty incomes by pillaging and slave-gathering raids into Northumbria. Nowhere in the North West is there as yet evidence for towns. (Summerson 1993, I, 7)

Little revenue reached the English king from his nominal subjects in our region. There were few royal estates in Yorkshire and further north to serve as counterweight to the possessions of northern magnates. Although the king retained the power to appoint earls and bishops, his choice was constrained by the need to choose men capable of dominating a rough and divided society.

The disturbed state of the north was enhanced by the invasion and conquest of England by the Scandinavian king Cnut (Canute) in 1015–16. This involved the fall from power of the Bamburgh dynasty of earls. (Morris 1992) The Scottish threat culminated in a defeat of the Northumbrians at Carham, probably in 1018, which ended any possibility of a recovery of Lothian, the extensive region between Tweed and Forth which had previously been dominated by Northumbria. Our region now comprised a vulnerable border territory. Scotland could threaten the north of England on two fronts, east and west, or a combination of the two. (Kapelle 1979, 34, 38–9, 93)

The Role of Siward

Intervention by English kings in the troubled affairs of the North was sporadic. Cnut moved north some time around 1030, and enjoyed sufficient success to receive the formal submission of the king of the Scots. About ten years later the Scots took the offensive, but King Duncan’s siege of Durham ended in failure. For some time a measure of stability returned when Siward, who had been earl of York since 1033, also became earl of Northumbria, probably in 1041. He was a shrewd adventurer from Denmark, who had risen to prominence under Cnut and his sons. His success allowed him to retain his position after 1042, when the House of Wessex in the person of Edward the Confessor was restored to the English throne, if only because he was needed if order was to be maintained in Northumbria. Edward added to the resources of his northern viceroy, granting the earl the shires of Northampton and Huntingdon in addition to his northern satrapy.

In the north, Siward seems to have exercised a pre-eminence similar to that built up by Earl Godwin in the south, even if his relationship with Edward the Confessor was not clearly established. (Higham 1993, 232) His position was stronger in Yorkshire, where Viking influence remained strong, but Viking predominance was not popular further north. It is unlikely that the earl’s hold on Cumbria was more than precarious overlordship, with local magnates enjoying practical autonomy. Even this degree of success depended on diminishing the influence of the Scots, whose position in the North West may have been maintained since the later tenth century. One of the earliest documents relating to Cumbria’s history, a mid-eleventh-century charter issued by Gospatrick, contains only a ‘gesture of deference’ towards Siward, rather than recognition of effective suzerainty. (Summerson 1993, I, 8; Rose 1982, 122; Barrow 1973) Despite the extent of his apparent jurisdiction, Siward had problems, although his resistance to Scottish aggression helped to sustain his authority. He strengthened his position by marrying Aelflaed, daughter of one of the last native earls of Northumbria, from the house of Bamburgh, who brought him some of her family’s northern estates as well as its prestige. (Morris 1992)

Siward’s power depended upon his household retainers, trained and well-equipped professional soldiers. Maintenance of this household and its governing functions was sustained by substantial landed estates and shrewdness in balancing potential sources of trouble against one another. Events in Scotland provided him with unexpected opportunities to consolidate his position.

The death in 1034 of the aggressive Malcolm II of Scotland, who had frequently invaded Northumbria and Strathclyde, was followed by the murder of King Duncan in 1040 by Macbeth, who seized the Scottish throne. Duncan’s son, Malcolm, with other leading princes, fled to England and asked for help to overthrow the usurper. Siward took advantage of Scottish difficulties to undermine Scottish control of Cumbria, and took over southern Strathclyde at least as far as the Solway by mid-century. Even if his authority there was limited, this brought English control over routes for possible attacks from the west, the Tyne-Solway gap and the Stainmore pass.

In the mid-1040s, Siward tried unsuccessfully to replace Macbeth with a friendly king from among the Scottish exiles. In 1054 Siward invaded Scotland, accompanied by Prince Malcolm. The importance of the expedition is shown by its wide support. The situation in the North West at this time remains obscure. At some time in the 1050s the Carlisle area was held by a member of the Northumbrian house of Bamburgh, possibly as a Scottish satellite ruler, but Siward’s army included a large Cumbrian contingent. King Edward contributed some of his own household troops. Although Siward was victorious, the decisive battle of Dunsinane, on 27 July, brought heavy casualties on both sides. The deaths of Siward’s son, Osbeorn, his nephew, and other prominent members of the next generation of leaders of the English North were to have serious consequences. Macbeth fled and survived for three years before being killed. The new Scottish king, Malcolm Canmore, owed the English a debt of gratitude, but Scottish goodwill could not be counted on at times of English weakness.

Siward died the year after his Scottish campaign, having ruled the North for more then twenty years. His dominance had provided relative stability after the confusion and conflicts of earlier years. If Siward’s subordination to the English king was limited, these years saw progress towards establishing the region as part of the wider English kingdom. Siward enforced appointment to the see of St Cuthbert of its first bishop from the south, rather than any of the Northumbrian factions. The bishopric was already developing a special status, associated with the sanctity of St Cuthbert, and its control was crucial for the Durham area. (Bonner 1989; Rollason 1994) The overlordship of Edward the Confessor was now at least nominally recognized in virtually the whole of what was to be the kingdom of England during the centuries to come.

The Problem of the North

The succession to Siward as earl of York and Northumbria in 1055 posed problems. His surviving son, Waltheof, was only a boy. (Morris 1992) Edward did not choose the local alternative from the House of Bamburgh, but instead appointed an outsider from the south, Tostig, third son of his most powerful subject, Earl Godwin. This may have been intended to further integrate Northumbria within the English kingdom. (Lomas 1992, 9) The House of Godwin was powerful and ambitious, but the appointment was something of a gamble, as Tostig had no power base in the north and none of Siward’s prestige and influence.

Tostig failed in the difficult task of controlling Northumbria, although his catastrophe was postponed until ten years after his installation in 1055. To establish his power, he needed resources to sustain an adequate retinue, and this meant squeezing more revenue from the earldom. Some local feuds were deeply entrenched, including disputes between the bishop and the Durham quasi-monastic community. Siward’s bishop retired soon after the old earl’s death and Tostig secured the appointment of that bishop’s brother to the see. Quarrels broke out again, and the community of St Cuthbert was alienated from the new earl. The Durham Congregatio had originated as an orthodox Benedictine community at Lindisfarne, but its subsequent adventures had transformed it into a society of men who performed monastic duties but could marry and have children. Many of them were drawn from influential northern families, and the marriage of a daughter of their bishop to an earl of Northumbria had seemed normal enough in the early eleventh century. (Bonner 1989; Morris 1992) Tostig’s alienation of a community possessing both spiritual and secular power was a serious weakness.

Tostig did not possess the resources with which to resist Scottish aggression. Malcolm had established his authority by 1058 and no longer needed English support. The Scots remembered how Siward had taken advantage of their troubles to move into Cumbria. Scottish raids began again, but in 1059 negotiations produced an apparently amicable settlement of current Anglo-Scottish disputes. Trusting in this, Tostig departed on a pilgrimage to Rome in 1061, accompanying Ealdred, the bishop of Durham. (Higham 1993, 235) This was the signal for a Scottish invasion. On the east, a devastating incursion ravaged parts of Northumbria. The Scots reoccupied Cumbria, which they were to hold for another thirty years. Their acquisitions probably went further, with places like Hexham and Corbridge uncomfortably close to the new border. North Tynedale seems to have been under Scottish control at this time. The Scots had acquired territories which enabled them to threaten the region from west as well as north.

Tostig’s failure to reverse this situation on his return further impaired his hold on his earldom. His financial exactions continued, and attempts to reduce hostility by murdering three prominent Northumbrian noblemen were counter-productive. In 1065, while the earl was away, his enemies struck. The Durham community played a part in fomenting rebellion, but the first blow was struck at York. A party of disaffected nobles and their followers broke into the city and killed the heads of Tostig’s household troops and many of their followers. There followed a general rising and massacre of the earl’s followers. The rebels moved south in force and enlisted outside support by installing Morcar, brother of Edwin, earl of Mercia, as their new earl. In this way they recruited the principal rival dynasty to the House of Godwin and avoided damaging disputes about the succession within their own ranks. The continuance of Viking influence was shown by the rebels’ demand that Edward the Confessor should accept that the Laws of Cnut were still valid; presumably Tostig had failed to honour edicts of the Viking king. A modern assessment of the 1065 northern rising considers it ‘a coup conceived and executed … with consummate skill, which reveals … full grasp of the intricacies of contemporary English politics’. (Higham 1993, 236–7)

Map 2 The probable northern border of England, 1066–1092

After G.W.S. Barrow, Feudal Britain (London 1956)

After negotiations in which Harold, Tostig’s elder brother and the most powerful man in the kingdom, took a leading part, a settlement emerged. The ailing king and Harold acquiesced in Tostig’s overthrow and the installation of Morcar as earl of York and Northumbria. Other claimants were also bought off. Osulf, head of the House of Bamburgh, was to become Morcar’s lieutenant in the north of the earldom; Siward’s son Waltheof became earl of Huntingdon and Northampton, part of his father’s old possessions. Tostig’s financial exactions were to cease.

Tostig fled abroad after his rejection by the dying king and his own brother, Harold. The childless Edward died on 5 January 1066 and Harold was crowned the next day. Despite his lack of hereditary right, Harold’s election was generally accepted. The new king possessed great influence within a kingdom which had recently seen little in the way of orderly hereditary succession. Edwin and Morcar made no demur, and presumably Harold’s acceptance of Tostig’s expulsion had taken account of the need to conciliate this rival family as Edward’s death approached. Before the 1065 northern revolt, Harold had married the widowed sister of the Mercian earl, and made a friendly visit to Morcar at York before Easter 1066. (Higham 1993, 238) Tostig had no reason to support his brother and resorted to raiding the south and east of England, before swearing allegiance to the king of Norway and joining him in a major invasion project. Harald Hardrada intended to restore England to Scandinavian rule as it had been in the days of Cnut, and gathered a powerful fleet. In seeking to understand Tostig’s behaviour, we should remember that concepts of nationality were embryonic, and that England represented a recent mingling of Anglo-Saxon, Celtic and Scandinavian inheritances.

The Norman Conquest in the North

The survival of Viking influences in Yorkshire made a landing there attractive to the Norse invaders. The Norwegian fleet was joined by Vikings from the Orkneys and Ireland as it approached England. At first the new English king waited with his highly trained household troops in the south, facing another rival, William, duke of Normandy. When he learned that the Norwegians had landed and routed Edwin and Morcar at Fulford Bridge near York, Harold set off north with picked forces. His speed enabled him to catch the invaders by surprise. In the Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25 September Harold won a smashing victory; Tostig and Harald Hardrada were killed. During victory celebrations, news arrived that William had landed in Kent. Harold set out by forced marches to meet this threat, but on 14 October he was defeated and killed. (Le Patourel 1971, 2–5) With few exceptions, surviving leaders of the kingdom accepted the Norman victory, and William was crowned at Westminster on Christmas Day 1066, claiming to inherit as legitimate heir of the Saxon rulers. For the time being, Morcar remained earl of Northumbria and attended William’s coronation, although the king did not allow him to return north.

The new regime inherited difficult problems, none more troublesome than the situation in the far north. English control was not yet solidly established, and opposition to southern interference remained potentially strong. Among nobles still holding out against William was Osulf of Bamburgh, while the new king must have had at least a suspicion that northerners had co-operated with Viking invaders a few months earlier.

William tried to deal with his northern province by installing Copsig as his chief representative there. Copsig had influential Northumbrian connections, though he had sided with Tostig in the Norwegian invasion of 1066. The new earl, with his household troops, came north early in 1067 to establish his authority, but failed to dispose of Osulf, whose followers surprised Copsig on Tyneside on 12 March. He fled into the church at New-burn, whereupon his enemies set the wooden building on fire, and Copsig was killed when he emerged. This catastrophe may be connected to Copsig’s attempts to gather taxes for William within a region always suspicious of southern tax-gatherers. The rebellion was weakened by the death of Osulf in a minor affray later in 1067, and this gave William a breathing space to try again to establish his authority in the north.

The failure of Copsig, and the king’s need for money with which to reward his followers of 1066, led to what was virtually the sale of the earldom of Northumbria to Cospatric, a nobleman with family connections in Northumbria and Scotland. His father was a Scottish prince, and his mother’s parents were a former earl of Northumbria and a daughter of Ethelred, king of England.

William I’s need for money led him to employ the tax-raising powers of his English predecessors. His first geld may have contributed to Copsig’s death, his second led to a rising against him in 1068. Edwin and Morcar rebelled in the spring, and Cospatric also joined the uprising. At the same time, the Saxon prince Edgar the Atheling, closest heir by blood to Edward the Confessor, was at large as a claimant to the English throne. William moved swiftly, forced Edwin and Morcar into submission, and occupied Yorkshire.

The northern surrender was only skin-deep. Cospatric and Edgar the Atheling fled to the Scottish ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of plates

- List of maps

- Acknowledgements

- General preface

- Dedication

- A Regional History of England series

- Introduction

- Part One: c.1000–c.1290

- Part Two: c. 1290–1603

- Part Three: 1603–c.1850

- Part Four: 1850–1920

- Part Five: After c.1920

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index