![]()

Section 1

A Social Learning Approach to Environmental Management

![]()

1

Social Learning: A New Approach to Environmental Management

Meg Keen, Valerie A. Brown and Rob Dyball

At a Glance

In the last 50 years, environmental management has become integral to a wide range of community, professional and government activities

Social change is needed if society is going to adequately address the environmental challenges threatening human societies and the global eco-systems on which they rely

We need a new approach to environmental management that supports collective action and reflection directed towards improving the management of human and environmental interrelations. We refer to this as the social learning approach

The social learning approach has three agendas – to create learning partnerships, learning platforms and learning ethics that support collective action towards a sustainable future

This chapter highlights three principal partnerships – with community, specialist areas and government

The five core strands of activity integral to the social learning approach and its agendas in environmental management are reflection, systems orientation, integration, negotiation and participation.

Caring for the Planet: It Takes a Community

There’s an old adage that claims ‘it takes a community to raise a child’. The community is needed because no one individual could possibly give the child all the love, knowledge and experiences needed to nurture a well adjusted adult. In the same way, all members of society are needed to nurture a healthy environment. This holds at all relevant scales, be it the local community and its immediate environment, national policy-makers concerned with national environmental resources, or even the global community concern for processes at a planetary level. At all these levels, collective action needs strong alliances and a commitment to processes that allow us to work and learn together.

This book will not devote space to arguing that on many levels much improvement in environmental management is needed. Organizations as diverse as the World Bank (2002) and the United States Research Council (1999), and events such as the Johannesburg World Summit on Sustainable Development in 2002 and the World Social Forum in 2004, along with many others, have strongly pleaded for an urgent need to change. Headline indicators such as rapidly increasing energy and material consumption, growing income and wealth disparities, and declining species diversity all show a range of signs that suggests much needs to be done – and soon.

At the last World Summit on Sustainable Development in 2002 there was a strong multinational plea for partnerships that would allow communities, professionals and governments to jointly take action against the abovementioned trends. However, a lot of learning needs to be done to make these partnerships work. Imagine a community that is concerned about the steady decline of its inshore fishery. Catch and income have dropped, and people are leaving the town. An international non-governmental organization (NGO) offers assistance, as does the local government fisheries office, the marine studies department at the local university, the state urban planning department and the neighbouring community. Who’s going to learn what from whom? Are they learning about fish, marine ecosystems, social systems, property rights, economic incentives or some combination of these? What learning processes will be used to share ideas effectively and plan for action?

Social learning is the collective action and reflection that occurs among different individuals and groups as they work to improve the management of human and environmental interrelations. Social learning for improved human interrelations with the environment must ultimately include us all, because we are all part of the same system and each of us will inevitably experience the consequences of these change processes.

In the recent past, we have been reluctant to see either local or global environmental management as an integral part of our daily affairs. In the era of the industrial revolution, people became so removed from their natural environments that they ceased to see the interconnections between social and natural resources. We eat a banana from across the globe without knowing the social or ecological circumstances under which it was produced; we wash our hands, with little awareness of the catchments from which the water comes and where the waste water will go; and we turn on the heating, lights and television with little concern about the flows of energy we induce, or how they were generated. People working as environmental managers, in any field, have to contend with these disconnections that exist within communities, as well as those between communities and their natural environment. Part of an environmental manager’s job is to create learning experiences to re-establish the mental connections between our actions and environments, thus creating pathways for social change.

There is a general recognition throughout the environmental field that it is time to bring social learning and environmental management back together.

The Environmental Management and Learning Agendas

Environmental management has grown exponentially as a profession over the past half century. Originally a new and largely unwelcome idea, it has now grown to be a major branch in many, if not most, government and non-governmental organizations; and in almost all university programmes. The first ‘environment management’ jobs appeared in the 1950s as junior posts, typically involved in ‘cleaning up the mess’, whether as pollution control officers or dog catchers. At that time there were no federal, state or local government departments responsible for environmental management, and no industry would have dreamt of such a thing. Within community sectors, the environmental organizations that existed were mostly concerned with field studies and nature walks.

Environmental legislation was slowly and somewhat reluctantly introduced into a number of countries and jurisdictions. In the US it took several tries, in various guises, before the National Environmental Protection Act was passed in 1969. This act, and similar legislation that followed around the globe, required all developments likely to have a ‘significant’ impact on the environment to undergo an environmental impact assessment. Unfortunately the legislation did not clearly define ‘significant’ and assessments were considered to be ‘one-off ’, or ‘undertaken and forgotten’ (Modak and Biswas, 1999; Thomas, 2001). As environmental problems mounted, environmental protection agencies were created, although they were typically not well funded and functioned primarily as reactive organizations. Without resources or power, these first agencies could not support a process of social learning or foster the necessary change process for improving environmental management and social wellbeing.

Across much of the world today there are few levels of government without environmental management units and legislation. Environmental management or services divisions are in almost all major global corporations, with many now putting into place certified environmental management systems to ensure continuous improvement in their environmental performance (Sheldon, 1997). There is a thriving profession, with its own subsets of consultants, environmental engineers, environmental health practitioners, environmental planners, environmental economists, environmental lawyers and environmental educationalists. And finally, although still reluctantly, we have agreed that global action is necessary on a number of issues. Multilateral agreements on the environment have been put in place to direct our collective actions on issues such as ozone depletion, deforestation, desertification and climate change, and most nations have endorsed a collective action plan, Agenda 21.

Modern environmental managers recognize that there is a need to address the sociopolitical causes of biophysical environmental problems, rather than only focusing on those problems. Environmental management has expanded to become environmental governance, the concern of all citizens at every scale of society. The accepted phrase for the main task of environmental managers since 1987 has been ‘sustainable development’, understood to be a balance between economic development, social equity and environmental sustainability (WCED, 1987). There is now a much broader concern to re-establish global ecological integrity for the future, and to create a just and healthy human future (Soskolne and Bertollini, 1998). This broader perspective is most frequently found under the banner of ‘sustainability’.

These changes have meant that the traditional field of environmental management professionals, consisting of ecologists and other biologists, has expanded to include a diverse subset of people from nearly every other conceivable discipline. Associated with this diverse membership is the need for these professional and interest groups to work and learn together in collaborative transdisciplinary groups. This collaboration is recognized as a prerequisite to achieving the necessary progress on environmental management, whether understood in the context of sustainable development or the broader concept of sustainability.

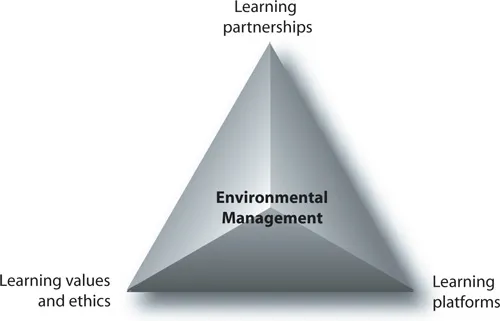

Social change is now inevitable, whether or not we choose to act. Faced with the facts, most of us will want to re-orient society and our approaches to environmental management in order to sustain our planet and ourselves. Now, more than ever, we have a strong motivation for a new approach to environmental management based on three new agendas. Firstly, we need equitable learning partnerships between the combined expertise of communities, professions and governments. Secondly, we need learning platforms that enable interdependent individuals and groups concerned with common environmental issues to meet and interact in forums to resolve conflicts, learn collaboratively and take collective decisions towards concerted action (Röling, 2002). Thirdly, social change requires a transformation in our thinking and in the learning values and ethics that underpin learning processes (see Figure 1.1). As noted by Einstein, ‘you can’t solve a problem with the same thinking that created it’.

Figure 1.1 The social learning approach to environmental management

The Strands of Social Learning in Environmental Management

Social and ecological sustainability ultimately depend on our capacity to learn together and respond to changing circumstances. Many current environmental management approaches claim to be ‘integrative, participatory and adaptive’, but there is a tendency for them to be more of the same. Partnerships occur within traditional disciplinary or managerial enclaves; actions are hampered by old institutional and social arrangements; and visions are constrained by the values and ethics that created the problems initially. The approach to social learning presented in this book is distinct and goes beyond these existing methodologies and the conventional, and problematic, traditions they bring with them.

We take an explicitly transdisciplinary approach by drawing out lessons from adaptive and participatory approaches to environmental management that are relevant to social learning. These insights are complemented with other useful concepts including those from systems analysis and organizational learning theory. Initiatives that take this transdisciplinary approach are already making a positive contribution to creating social learning partnerships, building platforms to support sustainability across multiple scales and disciplines, and fostering a social ethic of environmental care. In this book ten examples of social learning initiatives are presented from a range of sectors, such as community, government and professional. To assess these initiatives we develop and use orienting concepts, or strands of social learning.

The five braided strands of social learning that appear to be crucial to environmental management are shown in Figure 1.2. They are braided in the sense that they interact and overlap, yet each has an important role on its own. We discuss each of the five strands (reflection, systems orientation, integration, negotiation and participation) in the subsections to follow, and then combine the strands to provide a framework for analysing the case studies to follow.

Figure 1.2 The five braided strand...