- 238 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Learning Music Theory with Logic, Max, and Finale

About this book

Learning Music Theory with Logic, Max, and Finale is a groundbreaking resource that bridges the gap between music theory teaching and the world of music software programs. Focusing on three key programs—the Digital Audio Workstation (DAW) Logic, the Audio Programming Language (APL) Max, and the music-printing program Finale—this book shows how they can be used together to learn music theory. It provides an introduction to core music theory concepts and shows how to develop programming skills alongside music theory skills.

Software tools form an essential part of the modern musical environment; laptop musicians today can harness incredibly powerful tools to create, record, and manipulate sounds. Yet these programs on their own don't provide musicians with an understanding of music notation and structures, while traditional music theory teaching doesn't fully engage with technological capabilities. With clear and practical applications, this book demonstrates how to use DAWs, APLs, and music-printing programs to create interactive resources for learning the mechanics behind how music works.

Offering an innovative approach to the learning and teaching of music theory in the context of diverse musical genres, this volume provides game-changing ideas for educators, practicing musicians, and students of music.

The author's website at http://www.geoffreykidde.com includes downloadable apps that support this book.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

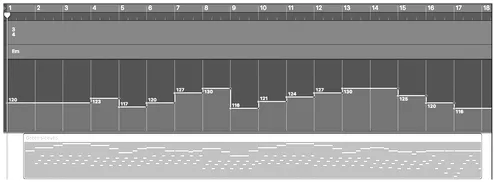

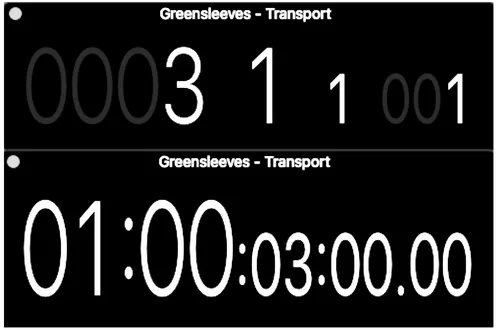

Rhythm: Tempo, Meter, Durations

1.1 Tempo

1.2 Meter

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Rhythm: Tempo, Meter, Durations

- Chapter 2: Rhythm: Loops and Advanced Rhythm

- Chapter 3: Pitch, Intervals, Scales

- Chapter 4: Triads

- Chapter 5: Seventh Chords and Extensions, Chord Patterns

- Chapter 6: Melody

- Chapter 7: Harmonic Progressions

- Chapter 8: Chromatic Harmony

- Chapter 9: Chromatic Music

- Chapter 10: Sound and Music Theory

- Bibliography

- Max Patchers and Objects

- Credits

- Index