eBook - ePub

Becoming an Effective Counselor

A Guide for Advanced Clinical Courses

- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Becoming an Effective Counselor

A Guide for Advanced Clinical Courses

About this book

Becoming an Effective Counselor is a textbook for advanced clinical courses that guides counselors in training through the most challenging phases of their academic preparation. Chapters blend skills-based content, real-world student examples, and opportunities for personal reflection to help students navigate some of the most difficult aspects of clinical counseling. Written by authors with over 50 years of combined counseling experience, this volume prepares aspiring counselors to assess their progress, remediate deficiencies, and deepen their existing skills in a way that is attentive to both core counseling skills and counselors' internal processes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Becoming an Effective Counselor by Justin E. Levitov,Kevin A. Fall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Challenge of Becoming an Effective Counselor

During his first semester of college, Chris decided that as soon as he finished his bachelor’s degree, he would directly enter a graduate counseling program. He had always wanted to be a counselor, and already was looking forward to greeting, evaluating, and treating his first “real client.” So strong was his interest that at some level he felt that the counseling profession selected him, not the other way around. After all, his friends had always sought him out when they were troubled or concerned about their problems with school, parents, or other friends. He was a great listener, and his concern for them was real. In addition, the personal trait that others found most remarkable was his uncanny insight. He could define a problem, explain why it was happening, and identify realistic solutions better than anyone else could. He finished his undergraduate program in record time and was immediately accepted into the school’s graduate counseling program.

While Chris enjoyed the counseling theory and practice courses as well as the counseling electives, he found them useful only to a point. Early in his graduate training, Chris predicted that practicum and internship would be mostly a matter of continuing to do what he had always done so well with his friends. He would just listen carefully, determine what they needed to do, and then advise them to do it.

As the time for practicum approached, Chris, unlike his peers, seemed unconcerned about the choice of a field site. He was confident that wherever he went, he would succeed. He continued as he had through most of his training, spending more of his time assisting other students with their myriad concerns rather than focusing on his own. Since he and his classmates were now in the process of selecting field sites, he would carefully question others about where they wanted to work, what types of clients they would most prefer, and what they planned to do when they graduated. Once again, his insights proved invaluable to his cohorts as they refined their site choices and began to face this important element of their training.

As the course began, weekly group supervision meetings were filled with the questions with which all counseling novices struggle. Chris reflected on each one and rarely missed an opportunity to share his insights with other members of the group. Yet although he was sure that his advice was accurate and useful, he grew increasingly frustrated as one student after another seemed to become less interested in what he had to say. By the third week of supervision, Chris had become unhappy; at times he secretly dreaded having to attend the weekly group meetings. What’s more, he sensed a struggle building with his site supervisor. Chris felt insulted when his site supervisor questioned him about why he rarely brought up questions about his own clients during group supervision meetings, preferring to discuss problems that other students were having at their field sites rather than addressing his own concerns. Unfortunately, Chris misread the supervisor’s intent when he incorrectly concluded that the supervisor was intimidated by him, a student with many natural skills needing very little direction.

It was not until the sixth week that Chris began to wonder about his progress in a more thoughtful and reflective way. He had completed intake evaluations on four clients. Two had not shown up for the next scheduled counseling session, and one had asked for a transfer to another counselor. Chris was now becoming worried, confused, and at times angry about these developments. He knew that his advice was good and that the clients should be listening, but they were not. He found them frustrating. He wondered why these people weren’t more enthusiastic about returning to meet with him and more willing to do what he recommended. His certainty about the clients’ needs and the clarity of his expectations of them made the fact that they would not engage with him in the process of counseling all the more baffling. He knew things were not going well, but he was at a loss to explain why.

Chris’ supervisor sensed his level of frustration and suggested that Chris come to his office for an individual meeting. The supervisor recognized Chris’ strengths and abilities, but he also knew that the way Chris was conceptualizing the process was interfering with his ability to properly manage the important relationships that form the basis of clinical training. Though brief, the individual meeting seemed to help. Soon after, Chris began to move away from advice- giving and directing clients and toward developing his relationships with not only clients but supervisors, peers, and even himself. This redirection produced results. Within weeks Chris was experiencing a redefined sense of purpose, greater comfort with the process, and a decrease in frustration levels. He actively participated in supervision by raising questions about his assigned cases, encouraging comments from others, and becoming more open to suggestions. He looked forward to counseling sessions, supervision meetings, and peer meetings. Most of all he was relieved that his caseload was growing and clients were returning for regular sessions.

Introduction

Chris’ transition into supervised clinical work contains many useful lessons for you as you make the same shift in your training. We realize that Chris’ transition will be most valuable to you when it becomes a platform for discussion with your classmates and instructors. At the same time, Chris’ experiences usefully illustrate how at least one intern faced the challenge of simultaneously managing knowledge of theoretical information and key elements of his own personality as he tried to constructively relate to clinical supervisors, peers, faculty, clients, and himself. According to Kiser (2015), “[p]erhaps the greatest challenge for students in a human service field experience is not one of ‘possessing knowledge’ but one of ‘making use of’ that knowledge in practical ways” (p. xv). Though a complicated and demanding process, developing effective clinical competencies is also intensely rewarding. You can expect this process to produce a wealth of new insights about yourself and a greater appreciation for the forces that will help you develop into a competent, trained professional. As you enter this phase of your training, you should derive some comfort from the knowledge that you are about to negotiate the same path that every mental health professional before you followed as he or she underwent the critical professional transformations that advanced clinical courses produce.

Careful planning and personal preparation for advanced clinical experiences dramatically improve outcomes. Historically, counselor training programs exhibited a wide distribution of positions regarding clinical training. Stances ranged from sending students “off on their own” to find and complete fieldwork to providing carefully planned and highly organized courses with articulated agreements between the university, the field site, and the field supervisors. Ethical guidelines for the training of counselors have aspired to ensure that the appropriate amount of time and attention is paid to this critical aspect of training. While these improvements have helped, you can also contribute by becoming thoroughly familiar with ethical codes, developing a willingness to learn more about yourself, exploring methods of enhancing the effects of supervision, and being prepared to identify the types of clients and agencies you would find most valuable.

Because the counseling process relies so heavily upon the counselor-client relationship, each counselor must develop a clinical style that not only honors the counselor’s individual character but also meets the multiple requirements of a healthy and effective clinical relationship. This reality, coupled with what we have gleaned from our teaching and supervision experiences, suggests that while you are obligated to make this transition from theory to practice, you must do so in your own way. This text focuses on helping you make this transformation while honoring the unique elements of your personality and character.

Mixed feelings about this portion of your training are common. If you are eager to begin seeing clients but worried about how you will balance all of the elements that combine to form a successful clinical experience, you are not alone. Taking an academic course for credit and completing a clinical course place very different demands upon you. It is one thing to study theory and quite another to apply theory in combination with key elements of your own personality so that you can craft an approach that allows you to ethically and effectively help others. The complexity of the task becomes clearer when you recognize that (a) each counselor is a unique individual, (b) each client is a unique individual, and (c) there are a number of different theories from which to choose. Any practical study of how these three highly variable components interact would be challenging. Fortunately, insights about yourself combined with your personal relationship to counseling theory, other professionals, supervisors, agencies, and, ultimately, clients follow predictable patterns. These patterns define and explain the forces that govern relationships, and these forces can be refined to improve your efforts to be helpful to others.

As noted earlier, unlike content courses, clinical courses produce a constellation of personal and professional responsibilities for which students must carefully prepare. Fortunately, supervisors and professors can help you because of their training and experience and because they traveled the path that you are about to embark upon. Their wisdom is available and useful. Most skilled clinicians are happy to answer questions about their clinical training experiences and many will offer useful suggestions. This book explores these relationships and offers suggestions on how you can translate theory into effective clinical practice. It is important to be thoughtful about these ideas because habits and patterns formed at this early stage are likely to endure throughout the course of your professional life.

Relationships

You will encounter various types of relationships during your clinical training. Each one is critical to your professional development; in the aggregate, they will combine to help form you into a skilled clinician. While the counselor–client relationship may be the most obvious, a number of other equally critical relationships exist. By carefully addressing each of these, you will discover valuable sources of information, support, guidance, and understanding. Ultimately, what you learn as you negotiate these relationships will greatly benefit your counselor–client relationships.

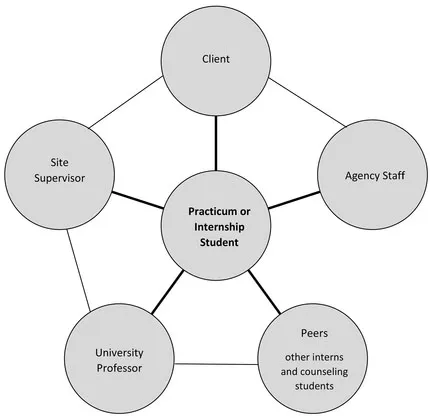

The following relationships and the term used to describe each, offered in no specific order, compose the types of interaction you can expect during your clinical work:

| Student-Professor | Faculty Supervision |

| Student-Site Supervisor | Site Supervision |

| Student-Student | Peer Consultation/Peer Relationships |

| Student-Agency Staff | Work Relationships (Other Professionals and Support Staff) |

| Student-Client | Counseling Relationship |

Just as a majority of mental health professionals subscribe to the notion that within the counselor–client dyad, it is the relationship that heals, (Baldwin & Imed, 2015; Norcross & Lambert, 2011), counselor educators would likely agree that the five basic professional relationships listed above form students into trained counselors. These relationships, along with the lines of communication, are illustrated in Figure 1.1.

The network of interaction depicted in the figure reveals a range of opportunities for you to learn about self, others, and the mental health profession. Some of these encounters can produce personal reactions that are worrisome or disquieting while others may be positive and easy to embrace. Because of the potential for such a wide range of personal reactions, it is essential that professional relationships and mentorships be constructed upon a solid foundation formed from honesty, trust, respect, understanding, knowledge, and a shared commitment to personal and professional development. Reliance on such a foundation ensures that clinical training experiences can be used consistently to improve yourself, regardless of how personally difficult they may be. Learning new things about yourself, managing anxiety and uncertainty with greater skill, and developing better methods to communicate and work with people are as valuable to you as a counseling student as they are to the clients with whom you work. Improving your ability to interact in all five relationship areas ultimately ensures greater levels of success in the counselor–client relationship.

Figure 1.1 Important Relationships for the Developing Professional

Counselor Formation

Because we believe that the effects produced by these five core relationships are so central to the process that transforms students into clinicians, we prefer the term counselor formation to counselor training when describing the process. The term formation implies that necessary ingredients for effective counseling (as well as those that may obstruct efforts) coexist within you. As a trainee, you will encounter professional relationships that will help evoke these qualities. This perspective is both realistic and optimistic. The idea that counselors are formed instead of trained beckons supervisors and faculty to develop modes of interaction that honor your uniqueness, help you draw upon those characteristics of yourself that enhance your skills, and simultaneously manage those aspects of self that may interfere with your efforts to be helpful to others. Such relationships with supervisors and colleagues can motivate and guide you toward a process of continuous self-improvement, a goal shared by most skilled mental health professionals. What makes you unique is as important to the development and maintenance of the critical relationships that form the basis for counseling as any theory or collection of clinical skills. As Auxier, Hughes, and Kline (2003 point out,

[c]ounselors’ identities differ from identities formed in many other professions because, in addition to forming attitudes about their professional selves, counselors develop a ‘therapeutic self that consists of a unique personal blend of the developed professional and personal selves [Skovholt & Ronnestad, 1992, p. 507]’.

(p. 25)

Counseling: Art and Science

Counseling is both an art and a science. As a science it relies heavily upon a growing body of research and theory to guide decision-making and to encourage the proper use of counseling strategies. Advances in psychopharmacology, discoveries of more effective treatment protocols for specific types of psychological problems, and refined diagnostic criteria emphasize the importance of recognizing the more-scientific elements found in effective counseling. At the same time, “the practice of professional counseling is certainly not an objective science” (Osborn, 2004, p. 325) and because of its subjectivity, the counseling process calls for more-ambiguous yet equally useful skills of interpretation, expression, and relationship building, all of which are important to counseling outcomes. Research findings are useful, but findings alone rarely influence individuals enough to make the difficult changes that are necessary to improve the quality of t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 The Challenge of Becoming an Effective Counselor

- 2 Ethics of Practice for Advanced Clinical Work

- 3 Clinical Supervision: Developing a Collaborative Team

- 4 Am I Doing this Right? Formative and Summative Assessment

- 5 Client Intake: First Steps in Forming the Alliance

- 6 Identifying Problems, Issues, Resources, and Patterns

- 7 Helping Clients Change

- 8 Termination

- 9 Post-Master's Supervised Clinical Experience, Licensure, and Employment

- Index