![]()

1

Biological Treatment Processes

1.1 Process Fundamentals

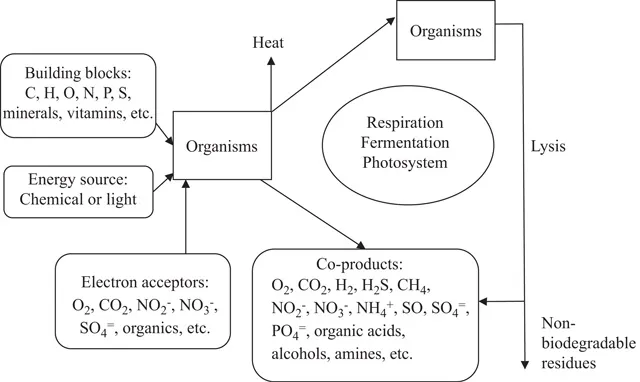

Biological processes involved in pollution control and bioenergy production are principally chemical reactions that are biologically mediated, and therefore can be otherwise referred to as biochemical processes. These biochemical reactions require external source of energy for initiation. In the case of biodegradable organics and other nutrients, the activation energy can be supplied by microorganisms that utilize these materials for food and energy. The sum total of processes by which living organisms assimilate and use food for subsistence, growth, and reproduction is called metabolism. Each type of organism has its own metabolic pathway, from specific reactants to specific end products. A generalized concept of metabolic pathways of importance in natural systems is shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 shows that in biological processes, the substrates, and available electron donors will be transported into the microbial cell and all by-products, including extra microbial biomass and waste products, will be taken out of the cell by physical and chemical (physico-chemical) processes. Organic substrates can be in soluble or particulate form. The soluble and simpler monomers can diffuse through the cell walls into the cell, while the more complex fractions and particulate matter can physically adsorb on the cell surface where they are hydrolyzed to soluble and simpler monomers by extra-cellular enzymes produced by the microorganisms. These monomers are subsequently transported into the cell. Hence, the biodegradation of colloidal, particulate, and long-chain organic matter takes longer time than the biodegradation of simple sugars and volatile fatty acids.

The adsorption process plays an important role in the removal of both biodegradable and nonbiodegradable materials. Microorganisms and particulate organic matter in general, including those produced during biological oxidation, have a higher adsorption capacity than inert materials due to their relatively higher surface area. The combined physico-chemical and biological processes associated with adsorption of pollutants is referred to as “biosorption.” Unless the adsorbed materials are biodegradable (i.e., they can be hydrolyzed and metabolized by microorganisms), their accumulation on microbial surfaces can eventually reduce the biosorption capacity of the biological treatment system. Changes in environmental and physico-chemical conditions within the treatment system can however result in the release of the adsorbed materials.

FIGURE 1.1

Generalized biochemical metabolic pathways.

1.2 Anaerobic Processes

1.2.1 Process Description

Biological processes in the absence of molecular oxygen, where the electron acceptors are carbon dioxide, organics, and sulfate (Figure 1.1) are generally referred to as anaerobic processes. These processes are similar to those that occur naturally in stomachs of ruminant animals, marshes, organic sediments from lakes and rivers, and sanitary landfills. The main gaseous by-products are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and trace gases such as hydrogen sulfide (H2S), hydrogen (H2), and a liquid or semiliquid by-product known as digestate. The digestate consists of microorganisms, nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, etc.), metals, undegraded organic mater and inert materials.

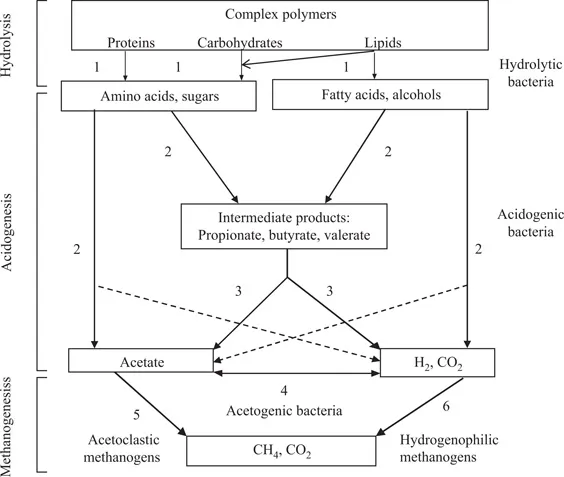

Anaerobic processes typically occur in four steps, namely hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis, as shown in Figure 1.2. Other processes that may also occur are nitrate and sulfate reductions, with ammonia or nitrogen gas and hydrogen sulfide as by-products, respectively.

FIGURE 1.2

Simplified schematic diagram of different reactions involved in anaerobic digestion of complex organic matter. (1) Hydrolysis: complex polymers are hydrolyzed by extracellular enzymes to simpler soluble products. (2) Acidogenesis: fermentative or acidogenic bacteria convert simpler compounds to short chain fatty acids, alcohols, ammonia, hydrogen, sulfides, and carbon dioxide. (3) Acetogenesis: breakdown of short chain fatty acids to acetate, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide, which act as substrates for methanogenic bacteria. (4) Acetogenesis: reaction carried out by acetogenic bacteria. (5) Methanogenesis: about 70% of methane is produced by acetoclastic methanogens using acetate as substrate. (6) Methanogenesis: methane production by hydrogenophilic methanogens using carbon dioxide and hydrogen. (Adapted from Kasper and Wuhrmann, 1978; Gujer and Zehnder, 1983.)

Hydrolysis involves the breakdown of complex polymeric organic substrates such as proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids into smaller monomeric compounds such as amino acids, sugars, and fatty acids. This reaction is facilitated by extracellular specific enzymes produced by a consortium of varied hydrolytic bacteria. The monomers released during hydrolysis are converted by bacterial metabolism of acid-forming bacteria also known as fermentative bacteria into hydrogen or formate, carbon dioxide, pyruvate, ammonia, volatile fatty acids, lactic acid, and alcohols (Mata-Alvarez 2003). Carbon dioxide and hydrogen gases are also produced during carbohydrate catabolism. In acetogenesis, some of the compounds produced by acidogenesis are oxidized to carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and acetic acid (acetate) by the action of obligate hydrogen-producing acetogens. In addition, acetic acid is produced during the catabolism of bicarbonate and hydrogen by homoacetogenic bacteria. Methanogenesis leads to the formation of CH4. The methanogenic bacteria use acetic acid, methanol, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen to produce methane gas and carbon dioxide. Seventy percent of methane produced is from acetic acid by acetoclastic methanogenic bacteria, making it the most important substrate for methane formation (Mata-Alvarez 2003). Thirty percent is then produced from carbon dioxide and hydrogen by hydrogenophilic (or hydrogenotrophic) methanogenic bacteria. A simplified representation of the biochemical processes is given in Equations 1.1 and 1.2; the former representing hydrolysis and acidogenesis, and the latter representing acetogenesis and methanogenesis.

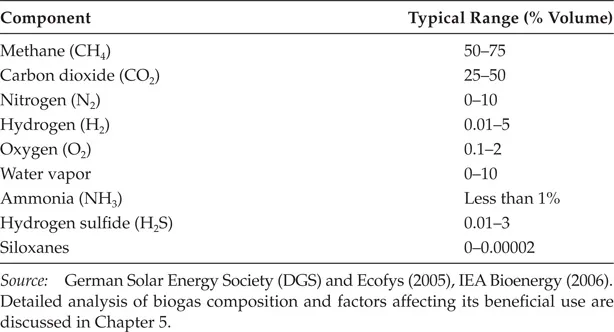

Table 1.1 shows a typical composition of gaseous by-products of functional anaerobic treatment process.

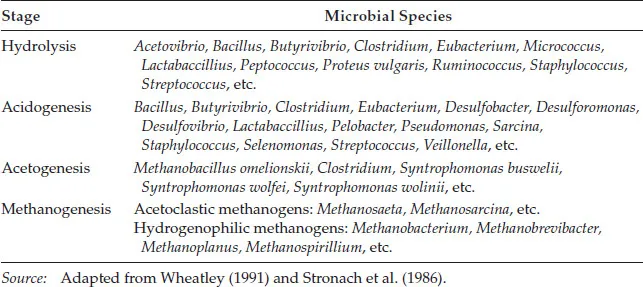

Some of the common key microorganisms associated with different stages of the process are listed in Table 1.2. In the absence of microbial inhibition, the distribution and balance of these microbial groups in any anaerobic biological processes system will depend on the nature of the available the substrates and the environmental conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, potential redox, etc.).

Anaerobic microorganisms can be suspended or can take the form of biofilm. Biofilm systems utilize various types of organic and inorganic materials as support media. They are able to retain a greater amount of biomass, and are generally more effective than suspended growth systems in wastewater treatment and hence are referred to as high-rate systems.

TABLE 1.1

Typical Biogas Composition of a Functional Anaerobic Treatment Process

TABLE 1.2

Anaerobic Digestion Stages and Typical Associated Microbial Species

In anaerobic wastewater treatment, biomass produced during treatment must be separated from the treated wastewater before disposal or further treatment. The selection of suitable solid separation methods will depend on the process type and the desired treated effluent quality. A separate gravity sedimentation tank may be used; some of the separated solids can be returned to the anaerobic system, and excess is disposed of. Current research has seen the development of more efficient separation techniques. One o...