![]()

1

Understanding Social Sustainability: Key Concepts and Developments in Theory and Practice

Tony Manzi, Karen Lucas, Tony Lloyd-Jones and Judith Allen

Introduction

We begin our discussions from a basic premise that:

Cities need to be emotionally and psychologically sustaining, and issues like the quality and design of the built environment, the quality of connections between people and the organisational capacity of urban stakeholders become crucial, as do issues of spatial segregation in cities and poverty. (Landry, 2007, p11)

From this starting point, the concept of ‘social sustainability’ can be described as the dominant element in discourses surrounding urban regeneration, both in the UK and elsewhere (Imrie et al, 2009, p10). However, different people mean different things when they discuss social sustainability. The purpose of this book is, therefore, to provide a better understanding of this concept in practical and conceptual terms. It does this by critically analysing how social sustainability has been applied within a variety of urban arenas; questioning how the notion of social sustainability operates in these contexts; and exploring the strengths and weaknesses of a variety of approaches. The main argument is that a ‘holistic’ approach to urban governance can only be understood by detailed reference to a range of interventions in urban policy.

Consequently, this book aims to:

Understand the main concepts applied to an analysis of social sustainability.

Explain how UK discussions about social sustainability can be linked to wider international developments.

Examine interlinked policy areas of intervention within urban policy.

Provide a critical account of contemporary interventions in urban regeneration.

This chapter will outline what we mean by social sustainability in the context of urban policy and urban development. The words ‘sustainability’ and ‘social sustainability’ have three different and inter-related components. First, they have a strong normative component, indicating a broad vision of a desired end state that is both holistic and long term. Second, they have a strategic component, indicating the desire to align a wide range of specific actions towards achieving the desired end state. Third, they have a descriptive component, which talks about ‘what is’ in terms of how it can be measured against strategy and vision (Colantonio, 2008a, 2009).

In order to define the meaning of social sustainability, this chapter adopts four approaches. First, we discuss how social sustainability is defined in relationship to economic and environmental sustainability. Second, we note the global nature of discourses of sustainability (international, trans-national, cross-national, intra-national, urban and localized) and outline the key elements of the international debates that are relevant to localized practices in the UK. Third, we discuss three concepts that are closely associated with visions of social sustainability: social exclusion, social capital and governance. Fourth, we consider UK and English policy on social sustainability, emphasizing the inseparability of political and policy thinking and issues about scale. Finally, we note some of the conceptual problems that need to be taken into account in discussing localized practices.

Conceptualizing ‘social’ sustainability: understanding multi-dimensionality

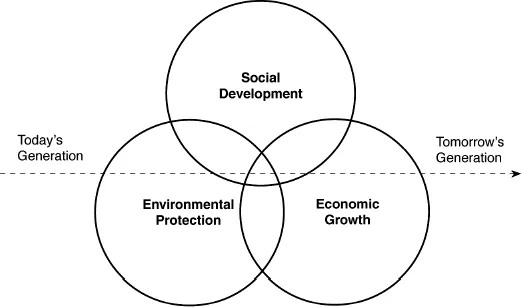

Despite a wealth of discussion about sustainable development, the concept remains unclear and contested. Most commentators agree that it lies at the intersection and implies policy integration of environmental, social and economic issues and the need to consider long-term change. However, there is no common position on the nature of this change or how it is to be achieved. There are many overlaps in the interactions between economic, social and environmental issues. Typically, in the sustainable development discourse (see, for example, Adams, 2006, p2), this is depicted in the form of overlapping circles (see the Venn diagram interpretation – Figure 1.1) or as concentric circles (see the ‘Russian Doll’ model – Figure 1.2).

The Venn diagram suggests there are potential positive-sum ‘win-win’ calculations in the overlaps, but also areas outside that need prioritization. If each of the circles is associated with the interests of particular stakeholders/actors, at whatever level of intervention, then the areas of overlap represent potential spheres of cooperation or partnership (Meadowcroft, 1999). The 1992 Rio Declaration suggests that sustainable development is about ‘balancing’ these three dimensions and achieving some kind of trade-off among them in the prioritization process.

Source: United Nations Non-Government Organization Committee on Sustainable Development website, www.unsystem.org

Figure 1.1 The dimensions and interactive process in sustainable development

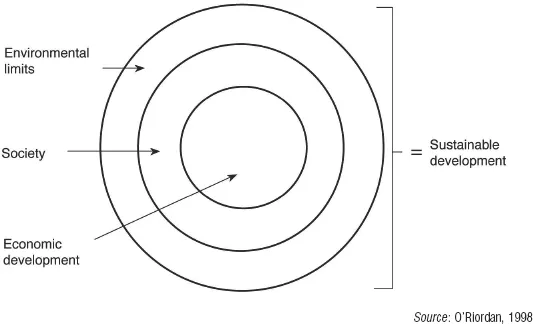

In contrast, the Russian Doll explanation (see Figure 1.2) suggests that sustainable development is primarily concerned with economic development, which must benefit society within strictly observed, unchangeable environmental limits.

In other words, the Russian Doll model downplays the importance of governance and negotiation in sustainable development. In contrast, we argue that these areas are of central importance in understanding social sustainability, and that the concept can be understood through a distinction between eco-centric and anthropocentric approaches to the question (Kearns and Turok, 2004).

Until recently, eco-centric models have dominated UK discussion, reflecting anxieties about environmental collapse, limited natural resources and the natural environment. The models emphasize the need for the efficient use of resources and are heavily influenced by environmental movements. They rest on implicit and explicit assumptions about the negative impact of human interventions on the natural world. In contrast, an anthropocentric approach focuses on human relationships, marking what is commonly referred to as social sustainability. As Kearns and Turok (2004) argue, this approach has become increasingly influential as it considers human needs and quality of life issues, as well as environmental concerns. However, some argue that anthropocentric approaches that take ‘soft issues’ into consideration may be more appropriate in the global north than in the global south, which struggles with the ‘hard issues’ of economic development and deep poverty (Colantonio, 2008b).

Figure 1.2 The Russian Doll explanation of sustainable development

It is clear that the nature of sustainable development is both complex and dynamic (Jarvis et al, 2001, p129), incorporating social, cultural, economic and community dimensions, demonstrating a strong interdependence between environment and people. Such interdependence can be interpreted through what Giddens (1986) would term a ‘structurationist’ framework, wherein the ‘environment, development and people should not be seen as discrete entities, as a dualism. Rather, they represent an interdependent whole, a duality of people's livelihoods and their environments’ (Jarvis et al, 2001, p130). As the boundaries between natural and built environments become increasingly blurred, issues about sustainability, or the lack of sustainability, are seen as essentially social problems – created by and eventually impacting on people themselves (Beck, 1992, p81); ‘nature can no longer be understood outside of society, or society outside of nature’ (p80).

Hence:

Social sustainability … is mainly concerned with the relationships between individual actions and the created environment, or the interconnections between individual life-chances and institutional structures … This is an issue which has been largely neglected in mainstream sustainability debates. (Jarvis et al, 2001, p127)

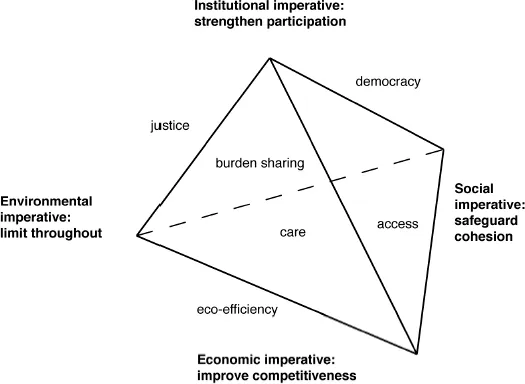

Therefore, the interdependent nature of social sustainability should acknowledge a political dimension; in particular by questioning how processes of power and control operate in urban policy contexts. As a consequence, a more useful conceptual framework involves a multi-dimensional understanding of social sustainability, as illustrated in Figure 1.3.

The benefit of such a multi-dimensional understanding is that it can provide a framework indicating how different social, economic, environmental and institutional imperatives influence the delivery of urban policy. These imperatives allow concepts of participation, justice, democracy and social cohesion to be introduced alongside more traditional concerns about the relationship between economic competitiveness and environmental efficiency. The relations involve difficult decisions about problem definition and agenda-setting; decisions that involve significant trade-offs or ‘burden-sharing’ among community members, dependent on priorities accorded at particular moments in time and upon specific resource constraints. The extent to which these different burdens are shared within communities forms a central part of the debate about what is meant by social sustainability and how it can be applied to different policy contexts.

Source: Centre for Sustainable Development, University of Westminster, and the Law School, University of Strathclyde (2006), p30 (adapted from EPA Ireland, 2004)

Figure 1.3 A multi-dimensional understanding of sustainable development

In this book, we argue that it is vital to understand the dynamic relationship between the different economic, social and environmental processes within the broad policy umbrella of sustainable development. This relationship may be cumulative and virtuous or there may be negative feedback effects. While some synergies do exist between a desire to protect the planet and human economic and social advancement, there are also important tensions between these often divergent policy goals. Throughout the book, this is a commonly recognized and repeated theme, reflecting a broad consensus in policy circles that achieving a balance between economic, social and environmental development is probably the greatest challenge for society today.

Think global: act local

To understand social sustainability we need to consider how it fits within the wider context of the debate surrounding sustainable development and the ways that have been put forward for achieving it. For this, a brief historical overview of the processes and circumstances whereby sustainable development entered the global policy arena is useful. The concept of sustainable development was introduced as a major social goal at the first United Nations (UN) Conference on the Human Environment, held in Stockholm in 1972. The conference was prompted by global concerns about the persistence of poverty and increasing social inequities, combined with growing local and global environmental problems and the realization that aural resources to support economic development were finite.

These concerns about scarcity of resources can be traced much further back. Fears that it may limit the growth of the human population informed Thomas Malthus’ classic work, An Essay on the Principle of Population (2008 [1798]). Rapid industrial development in the 19th century was accompanied by pollution and the growing concentration of people living and working in poor conditions in towns and cities. An era of social unrest and urban reform included movements concerned with the environmental health and well-being of the urban population. Proto-environmentalist ideas emerged in some strands of 19th-century radical and romantic thought. Meanwhile, strides were made in the scientific and systematic understanding of the inter-relationships among natural species, populations and their environments in Darwin's work on evolutionary theory and the origins of the science of ecology (Goodland, 1975).

However, it was not until the 1960s and growing protests against environmental pollution that these themes came together in focused thinking about the inter-relationship of human activity and the natural environment. Using a ‘systems’ approach and computer modelling, the ‘Limits to Growth’ Report to the Club of Rome (Meadows et al, 1972) explored the interactions between population, industrial growth, food production and the limits in the ecosystems of the Earth. The wave of sustainable-development literature expanded during the 1980s, when the International Union for the Conservation of Nature's influential World Conservation Strategy (1980) put forward the concept of ‘sustainable development’, meaning development that would allow ecosystem services and biodiversity to be sustained.

However, despite an emergin...