- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Food Security and Global Environmental Change

About this book

Global environmental change (GEC) represents an immediate and unprecedented threat to the food security of hundreds of millions of people, especially those who depend on small-scale agriculture for their livelihoods. As this book shows, at the same time, agriculture and related activities also contribute to GEC by, for example, intensifying greenhouse gas emissions and altering the land surface. Responses aimed at adapting to GEC may have negative consequences for food security, just as measures taken to increase food security may exacerbate GEC. The authors show that this complex and dynamic relationship between GEC and food security is also influenced by additional factors; food systems are heavily influenced by socioeconomic conditions, which in turn are affected by multiple processes such as macro-level economic policies, political conflicts and other important drivers. The book provides a major, accessible synthesis of the current state of knowledge and thinking on the relationships between GEC and food security. Most other books addressing the subject concentrate on the links between climate change and agricultural production, and do not extend to an analysis of the wider food system which underpins food security; this book addresses the broader issues, based on a novel food system concept and stressing the need for actions at a regional, rather than just an international or local, level. It reviews new thinking which has emerged over the last decade, analyses research methods for stakeholder engagement and for undertaking studies at the regional level, and looks forward by reviewing a number of emerging 'hot topics' in the food security-GEC debate which help set new agendas for the research community at large. Published with Earth System Science Partnership, GECAFS and SCOPE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Food Security and Global Environmental Change by John Ingram,Polly Ericksen,Diana Liverman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

FOOD SECURITY, FOOD SYSTEMS AND GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

1

Food Systems and the Global Environment: An Overview

Diana Liverman and Kamal Kapadia

Introduction

Food has always been linked to environmental conditions with production, storage and distribution, and markets all sensitive to weather extremes and climate fluctuations. Food production and quality are also sensitive to the quality of soils and water, the presence of pests and diseases, and other biophysical influences. Over millennia people have adjusted the production and consumption of food to the spatial and temporal variation in the natural environment, and the growing size and complexity of food systems have in turn transformed the landscapes that humans inhabit. The scope and scale of interaction are changing dramatically, particularly in relation to the risks of climate change, biodiversity loss and water scarcity; in terms of linkages to energy systems; and as food systems become more global in their networks of production, consumption and governance. This has started to raise concerns about food security, not only in governments, but also for private sector and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

Global food security has been defined as ‘when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’ (FAO, 1996). Food security is underpinned by food systems that link the food chain activities of producing, processing, distributing and consuming food to a range of social and environmental contexts (see Chapter 2 and Figures 2.1a and 2.1b). The environmental context includes large-scale changes in land use, biogeochemical cycles, climate and biodiversity that collectively constitute global environmental change (GEC) now occurring at an unprecedented scale of human intervention in the earth system. These are discussed below.

What are some of the most important trends in food security and GEC and the interactions between them? Why are these interactions important and what steps are being taken to manage and govern them? This chapter provides background and initial insights into these questions – elaborated in subsequent chapters of the book – and illustrates the importance of these changes through case studies of the recent food price crisis and of the new proposals for integrating food systems into international climate governance. The recent warnings and debates about the interaction between GEC and food security are then summarized through a review of major reports, the media and shifts in the agendas of key development organizations.

Trends in food production, food consumption and food security

Food security is a function of many factors, of which the most important is access to food. This in turn depends on the balance between food prices, trade, stocks, employment and markets, and patterns of production and consumption of both food and non-food crops, livestock and fish.

Food production

While overall agricultural production has grown over the last century, trends since 1990 suggest that growth has slowed, especially in the developed countries, and that per capita production has levelled off in many regions. World food supply is very dependent on a few crops, especially cereals (e.g. wheat, rice, maize), oilseeds, sugar and soybeans. Just over 10 per cent of these are produced and traded from exporting regions including North America, Brazil, Argentina, Europe and Australia. Production of these commodities, as well as meat, rose over the last 50 years, but varied with weather conditions and with prices, which until recently were low, suppressing production. Meat and dairy production have grown faster than crops overall, driven by changing demand and price signals. In Africa, where smallholder agriculture still underpins food security, production is still low in many regions, especially in terms of yield per unit area.

Yields are only partly dependent on environmental conditions such as climate, soils and pests, and higher yields are usually dependent on the use of inputs such as improved germplasm, fertilizer, labour, pesticides, irrigation and machinery. Many inputs have become more expensive for farmers in recent years as a result of higher energy prices (which affect the cost of fuel and agri-chemicals) and reduced government subsidies, and because low commodity prices make inputs less affordable.

The gaps between actual and potential yields are considerable, especially in sub-Saharan Africa where maize yields of less than 2 tonnes per hectare are only 50 per cent of what could be achieved (World Bank, 2007). Closing the ‘yield gap’ requires not only a favourable climate (or good insurance and reliable and affordable irrigation) but also support for improved fertilizer use, technologies, access to markets and credit, and investment in physical and institutional infrastructure.

The overall amount of food produced is, however, also a function of the area under production which is limited by, for instance, land suitability and the availability of irrigation, and other demands on land-use including non-food crops such as biofuels and fibre. It is also very sensitive to price signals. For example, when prices rose rapidly in 2007, producers expanded the area under production and cereal production increased by 11 per cent in the developed countries between 2007 and 2008 (FAO, 2009a). However, production increased by less than 3 per cent in developing countries, due in part to poorer access to markets and inputs. The key point here is that production is dependent on both environmental and economic conditions (as well as other factors), and that although there is potential to increase production in many regions this may depend on higher price incentives to farmers that would reduce access to food by consumers (FAO, 2009a).

Food consumption

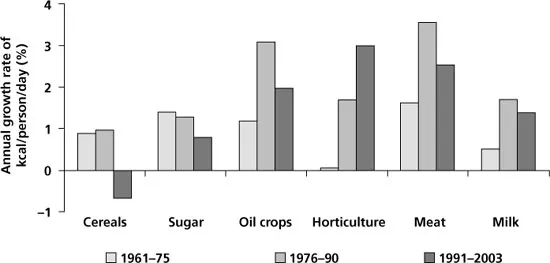

At the other end of the food chain, changes in consumption are having considerable impacts on food systems and food security. Overall consumption is likely to increase as global population rises, with estimates ranging from 8.5 to 11 billion by around 2050 – with recent UN projections suggesting a levelling off at around 9 billion. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) projects that demand for cereals will increase by 70 per cent by 2050, and will double in developing countries. Depending on economic conditions per capita demand is also likely to grow, especially in the developing world, with income growth in Asia especially important. The structure of food demand has changed substantially in the last two decades, especially in developing countries where food consumption is shifting away from basic cereals to fruits, vegetables, meats and oils (see Figure 1.1). Further, evidence from Latin America and Asia indicates that the pace of change in the structure of diets is speeding up. This shift in dietary preferences has far-reaching ramifications for the entire food chain: it is transforming the structure of production systems, the ways in which consumers obtain their food, and the nature and scope of food-related health and environmental issues facing the world. The reasons for these dietary shifts include income growth, urbanization and the spread of global processing and retail companies. Such dietary shifts are not, of course, uniform across all regions: total meat consumption in Asia has grown dramatically in the last decade, whereas it has increased only very slowly in North and South America (where it was already high), and increased very little or remained virtually unchanged in the rest of the world. On a per capita basis, meat consumption in most of the world, including Asia, is still less than per capita meat consumption in North America. Of all types of meat, the consumption, production and trade of poultry are growing the fastest, especially in developing and transition countries (Mack et al, 2005).

Source: World Bank, 2008. Original data source: FAOSTAT, Statistics Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Figure 1.1 Per capita food consumption in developing countries is shifting to fruits and vegetables, meat and oils

Demand for biofuels produced from agricultural feedstocks (whether food crops or cellulosic sources) is also likely to increase demand for agricultural commodities and resources, although the precise magnitude of this demand is highly uncertain, depending on energy prices as well as policy measures, especially in the developed countries.

Another trend in food preferences is the growth in processed food sales, which now accounts for about three-quarters of total world food sales. In developed countries, processed food makes up about half of total food expenditures; in developing countries it comprises only a third or less (Regmi and Gehlhar, 2005). Excessive consumption of meat, dairy and processed foods are contributing to the rapid spread of food-related health problems like obesity and diabetes, especially in the developed world. Nevertheless, such dietary transitions are not uniform across income groups. For the majority of the world's population and especially those living in poverty, cereals remain an extremely important source of calories: 90 per cent of the world's calorific requirement is provided by only 30 crops, with wheat, rice and maize alone providing about half the calories consumed globally (MA, 2005b). And for many of those living in poverty a modest increase in meat and dairy consumption can significantly improve nutritional status.

Food security

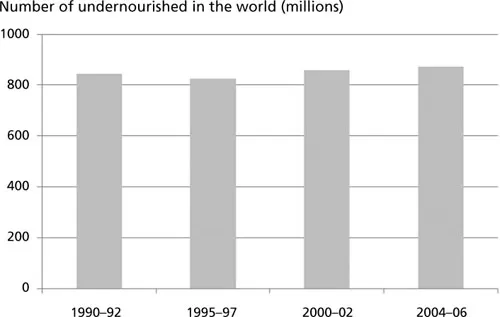

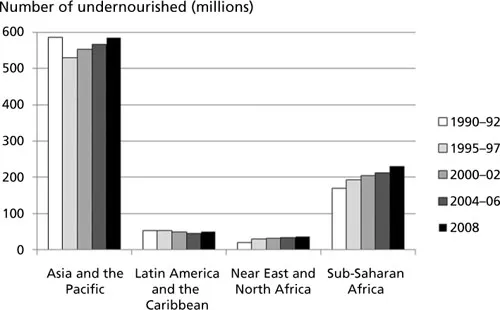

Overall growth in production and consumption has allowed some regions and people to become more food-secure but there are still millions of people who are undernourished and hungry and who do not have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life. A rapid rise in food prices in 2007–8 (discussed below) increased the number of hungry people to 923 million (FAO, 2009b), but even before the food price shock, progress on food security had been sluggish, and although the proportion of the population that was hungry dropped from almost 20 per cent of the population in the developing world in 1990–92 to just above 16 per cent in 2004–6 the total number of chronically hungry people stayed fairly constant through this period (see Figure 1.2). The number of hungry people increased again in 2008–9 (to more than 1 billion) because of the impacts of the financial crisis on access to food through loss of incomes. The ‘food crisis’ is discussed in more detail below. Further, increasing urbanization is changing the relationship between food demand and food supply, and the prevalence of food insecurity is increasing in urban areas (Frayne et al, 2010).

Source: FAO, 2009b. Original data source: FAOSTAT, Statistics Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Figure 1.2 Number of undernourished people

These numbers and trends also hide large regional disparities; Africa has the largest number of hungry people as a proportion of the population but Asia has the majority in terms of absolute numbers. However, in general, the overall availability of food is rarely a cause of food insecurity: 78 per cent of all malnourished children under five in developing countries live in countries with food surpluses.

There are also many different ways in which particular groups become food insecure – for subsistence producers the loss of access to productive land or the vulnerability of their crops, fish and livestock to climate, land degradation and pests may be the main threat to the food security of their families. For those farmers and fishers producing for the market, their incomes and food security will vary with commodity and input prices as well as environmental conditions, and they may be vulnerable to shifts in government policies and to default on debts should their harvests fail. Those employed in agricultural and food systems – including farm workers, distributors, labourers in food processing and small-scale retailers – are also at risk if they become unemployed or incomes fall as a result of environmental or economic conditions. All poor households that are net buyers of food (i.e. they consume more than they produce) are vulnerable to increases in food prices. It is also important to remember that food security is not just about the amount of food but also depends on the nutritional quality, safety and cultural appropriateness of foods (see Chapter 2 and Ericksen, 2008).

Food emergencies add to food insecurity when conflict, natural disasters or failed policies create production failures, interrupt distribution, or exacerbate poverty and ill health. The hotspots for this type of insecurity include several countries in Africa (Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo) and Haiti.

Trends in global environmental change

GEC includes changes in the physical and biogeochemical environment, either caused naturally or influenced by human activities such as deforestation, fossil fuel consumption, urbanization, land reclamation, agricultural intensif...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures, Tables and Boxes

- Editorial Committee

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- PART I FOOD SECURITY, FOOD SYSTEMS AND GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

- PART II VULNERABILITY, RESILIENCE AND ADAPTATION IN FOOD SYSTEMS

- PART III ENGAGING STAKEHOLDERS

- PART IV A REGIONAL APPROACH

- PART V FOOD SYSTEMS IN A CHANGING WORLD

- Index